Now in the works is a retro look back in time at a bizarre Cold War caper by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) thanks to a forthcoming, star-studded comedy/drama movie called “Lunik Heist.”

Earlier this month, Searchlight Pictures, a Disney-owned division, announced that actors Jared Leto, Lupita Nyong’o, and John Mulaney have signed on to star in “Lunik Heist,” described as a “a wild, roller-coaster ride, filled with subterfuge and unlikely heroes.”

The film is based on a real-life incident that saw CIA operatives plot to disassemble and inspect one of the Soviet Union spacecraft overnight while on exhibit during a 1959 expo in Mexico City.

Audacious plot

According to the Internet Movie Database (IMDb), Lunik Heist is in pre-production with filming locations in Atlanta, Georgia, Mexico City, Mexico, as well as Washington, D.C. and Arlington, Virginia.

You may like

The movie script is based on an article by Jeff Maysh, published in January 2021 within the pages of MIT Technology Review titled “Lunik: inside the CIA’s audacious plot to steal a Soviet satellite.”

That article by Maysh required significant research, such as poring over National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) documents about the history of the CIA’s Mexico City station, old CIA journals, and carrying out many interviews.

“The moment I learned about the Lunik incident, I knew I’d found my white whale … a heist story set during the space race,” Maysh tells Space.com.

“As I dug deeper into the archives, I realized this isn’t just another Cold War spy tale. It’s like ‘Oceans Eleven,’ only the big score is an interplanetary space station,” Maysh said.

CIA skullduggery

“The Kidnapping of the Lunik” was documented in a “sanitized” CIA historical review that was declassified and publicly posted in 1995. It was written by the CIA’s Sydney W. “Wes” Finer and published in the agency’s winter of 1967 edition of “Studies in Intelligence.”

A read of that document shows that the CIA skullduggery in Mexico City was also not wanting for comedic value, like a Humpty Dumpty replay of putting things back together again.

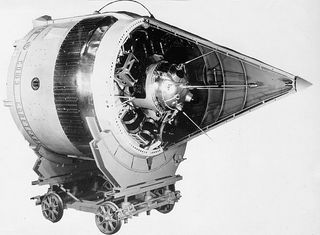

The CIA team was faced with gaining access to a cabin-like crate holding the Soviet space hardware that was approximately 20 feet long and 11 feet wide with a roof about 14 feet high at the peak. Brought into play were ladders, ropes, a nail puller, drop lights, extension cords and flashlights, including metric wrenches, screwdrivers and hammers.

“The first job, re-securing the orb in its basket, proved to be the most ticklish and time consuming part of the whole night’s work,” notes the document. Indeed, the way the nose and engine compartments were designed prevented visual guidance to easily reassemble the space hardware.

“We spent almost an hour on this, one man in the cramped nose section trying to get the orb into precisely the right position and one in the engine compartment trying to engage the threads on the end of a rod he couldn’t see,” the document points out. “After a number of futile attempts and many anxious moments, the connection was finally made, and we all sighed with relief.”

Covert operators and collectors

The CIA document observes that there was no indication the Soviets ever discovered that the Lunik was “borrowed” for a night.

Indeed, the results gleaned in the heist were published in a Markings Center Brief. “They included probable identification of the producer of this Lunik stage, the fact that it was the fifth one produced, identification of three electrical producers who supplied components, and revelation of the system for numbering parts that was used here and conceivably for other Soviet space hardware,” the document states.

“But perhaps more important in the long term than these positive intelligence results,” the document concludes, “was the experience and example of fine cooperation on a job between covert operators and essentially overt collectors.”

In-house journal

Noted space historian Dwayne Day first published a story that captured the CIA’s undercover work, noting Finer’s account in the British Interplanetary Society’s “Spaceflight” magazine in early 1997, an edifying go-to publication for information on historical, particularly Soviet Union space progress.

“Sometime in 1996 somebody told me that a huge batch of declassified CIA records had just become available at the National Archives facility in College Park, Maryland, so I drove up there to look at them,” Day recalls.

“The CIA declassified hundreds, maybe thousands, of articles from its in-house journal known as “Studies in Intelligence.” They were all photocopied articles in folders in archival boxes with a very rudimentary index. It was a laborious process to request boxes and then go through the folders,” Day told Space.com.

Day was looking for anything related to space and after a few hours of work came across the 1967 article by Finer.

Lunik label

“It was a fascinating account of an intelligence operation in an unnamed country where the CIA secured access to a piece of Soviet space equipment in order to examine it overnight,” said Day. “I knew that was an incident that had never previously been reported anywhere.”

The treasure trove of declassified items also included fascinating articles about intercepting television and other signals from Soviet spacecraft in orbit, Day said.

“In the 2000s, I occasionally tried to follow up on the Lunik subject,” Day said. “It took me a while to get it through my head that “Lunik” was a Western nickname and not real.”

Day said he briefly contacted one of the operatives involved, “and managed to learn about some related operations to analyze that and other vehicles, but I never went after the story in detail.”

Intriguing scenarios

RELATED STORIES:

There are some intriguing scenarios perhaps associated with the CIA’s “borrowing” of Soviet space gear in Mexico City.

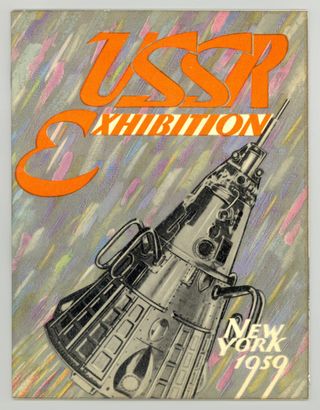

For one, the Soviet Union’s National Exhibition came to New York City in June 1959 and ran until late July. The focal point of the exhibition was Sputnik, including full-scale models of the first three Soviet Sputniks — and proudly on display was the “Lunik” mounted to its upper stage.

Did the CIA have multiple opportunities to study Soviet-era space paraphernalia and right there in New York City?

“I did know about the American exhibition and so did the CIA who sent spies, I believe,” Maysh said. “However, Mexico City and local operatives were chosen for plausible deniability. That’s my understanding.”

“It just goes to show what kind of incredible stories are gathering dust in government archives,” Maysh concludes. “At a time like this, we need to find more stories from the days when Americans outsmarted the bad guys and planted our flag on the moon.”