What’s the weather like at night on Venus? Scientists are finally finding out.

Just one planet away, Venus is relatively close to Earth and we have been studying it for a long time, with the first Venusian probe reaching the planet in 1978. However, scientists have known very little about what the weather is like at night on Venus. That is, until now.

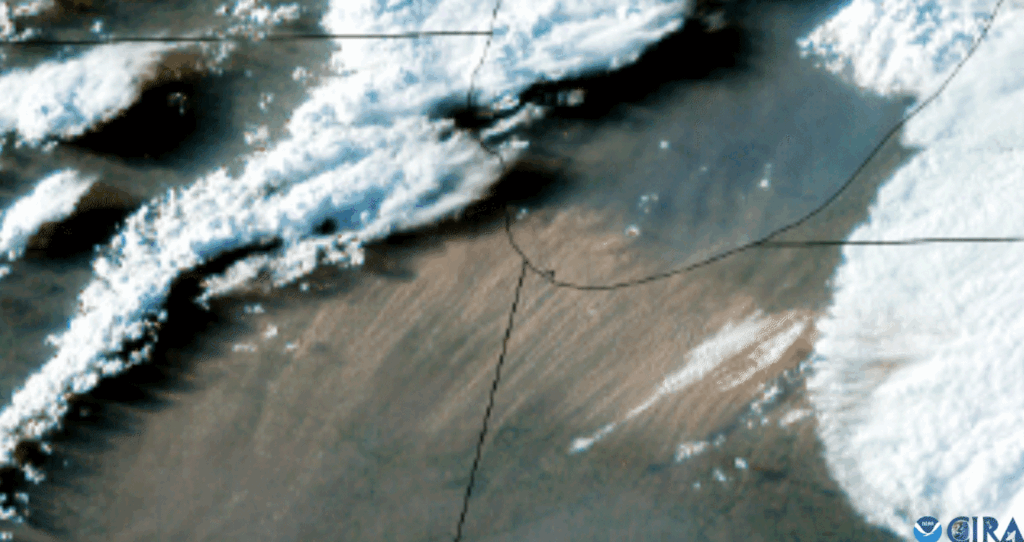

In a new study, researchers have devised a new way to use infrared sensors on the Japanese Venus climate orbiter Akatsuki, a probe that arrived in orbit around Venus in 2015, to finally reveal what weather is like on the planet at nighttime. Those sensors found nighttime clouds and some strange wind circulation patterns.

Related: Photos of Venus, the mysterious planet next door

Like Earth, Venus lies in our sun’s “habitable zone,” has a solid surface and an atmosphere that has weather. To understand a planet’s weather, researchers study cloud motion in infrared light. However, while Venus’ atmosphere rotates quickly, the planet itself has the slowest rotation of any major planet in our solar system, meaning day and night last quite a long time — about 120 Earth days each.

Until now, only weather on Venus’ “daylight side,” has been easily observable because, even in infrared it is difficult to get a clear look at Venus’ nightside. There have been infrared observations of Venus’ “nighttime side,” but these studies have not been able to clearly show the planet’s nighttime weather.

To explore this mysterious aspect of our neighboring planet, researchers turned to Akatsuki, the first Japanese probe to ever orbit another planet. The probe is designed to monitor Venus and its weather and has an infrared imager that doesn’t need sunlight in order to “see.” Despite this design, the imager hasn’t been able to capture detailed observations of Venus’ nightside. However, by using a new analytical method to handle the data captured by the imager, the researchers could indirectly “see” Venus’ elusive nighttime weather.

“Small-scale cloud patterns in the direct images are faint and frequently indistinguishable from background noise,” co-author Takeshi Imamura, a professor at the Graduate School of Frontier Sciences at the University of Tokyo, said in a statement.

“To see details, we needed to suppress the noise,” he said. “In astronomy and planetary science, it is common to combine images to do this, as real features within a stack of similar images quickly hide the noise. However, Venus is a special case as the entire weather system rotates very quickly, so we had to compensate for this movement, known as super-rotation, in order to highlight interesting formations for study.”

With this new analytical method, the team observed the planet’s north-south winds at night and found something quite strange.

“What’s surprising is these run in the opposite direction to their daytime counterparts,” Imamura said. “Such a dramatic change cannot occur without significant consequences. This observation could help us build more accurate models of the Venusian weather system which will hopefully resolve some long-standing, unanswered questions about Venusian weather and probably Earth weather too.”

Using this new method, the researchers think that future studies could reveal new details about weather on other planets like Mars or even our own planet Earth, according to the statement.

While this work uses existing technology in orbit around Venus, the planet will soon see three new missions arrive that will continue to expand our understanding of Venus and its climate. NASA recently announced two new Venus-bound missions, dubbed DAVINCI+ and VERITAS, and the European Space Agency revealed it will launch the EnVision mission to the planet. The three spacecraft will launch late this decade and in the early 2030s.

This work was described in a study published July 21 in the journal Nature.

Email Chelsea Gohd at cgohd@space.com or follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.