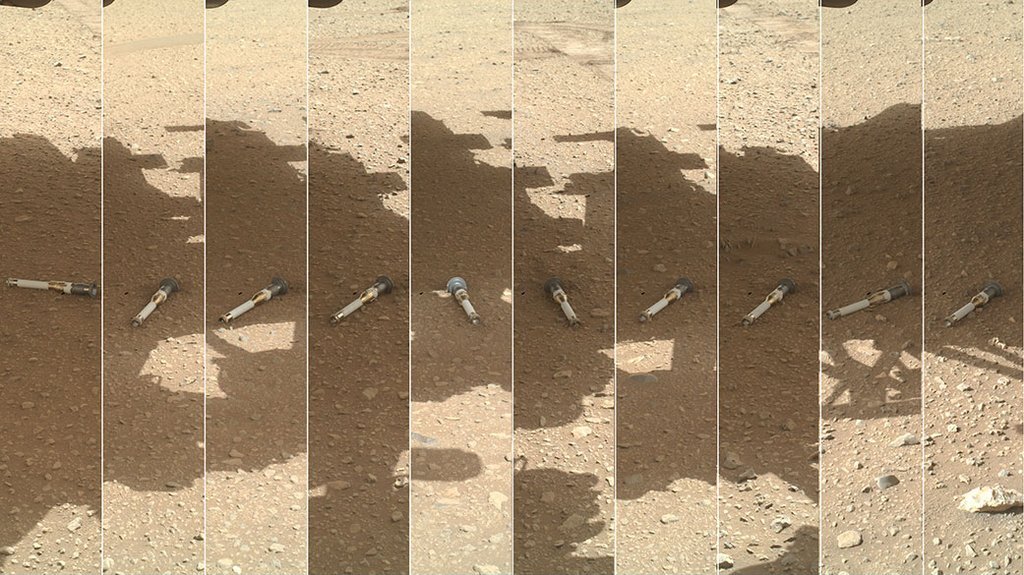

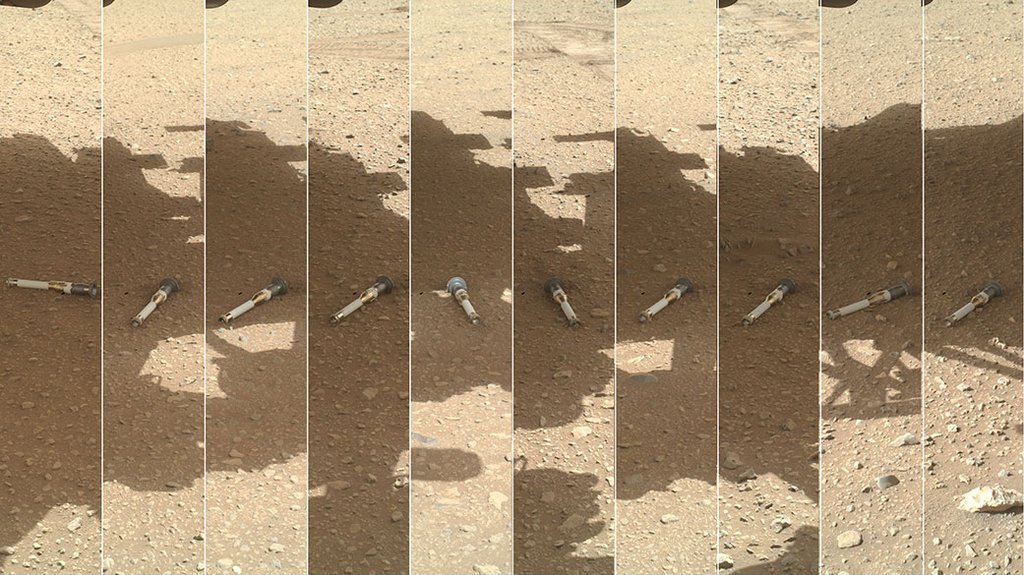

NASA’s Perseverance Mars rover has been on the prowl within Jezero Crater following its touchdown in February 2021. That car-sized robot has been devotedly picking up select specimens from across the area, gingerly deploying those sealed pick-me-ups on the Red Planet’s surface, as well as stuffing them inside itself. Those collectibles may well hold signs of past life on that enigmatic, dusty and foreboding world.

NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) have for years been intently plotting out plans to send future spacecraft to Mars and haul those Perseverance-plucked bits, pieces, and sniffs of atmosphere to Earth for rigorous inspection by state-of-the-art equipment.

But President Trump’s Fiscal Year 2026 proposed budget blueprint issued on May 2 by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) calls for a 24.3 percent reduction to NASA’s top-line funding and could slashing the space agency’s science budget by 47 percent. A casualty stemming from this projected budget bombshell is the Mars Sample Return (MSR) venture.

In fact, MSR is tagged in the White House’s proposed 2026 budget as “grossly over budget and whose goals would be achieved by human missions to Mars,” explaining that MSR is not scheduled to return samples until the 2030s.

The preliminary White House budget says its intent is in line with the Administration’s objectives of “returning to the moon before China and putting a man on Mars,” with the budget reducing lower priority research and terminating unaffordable missions such as MSR.

But some experts say that the mission still has a wealth of scientific and spaceflight returns to offer that are in line with the administration’s push to put humans on Mars.

Sticker shock

To understand why that mission got so costly, we must look to spaceflight history courtesy of John Connolly, a 36-year NASA veteran that directed human lunar and Mars mission designs. He is now professor of practice at Texas A&M University’s Department of Aerospace Engineering.

Mars Sample Return has been on NASA’s radar since mid-1970’s studies to modify a Viking Mars lander to perform a relatively simple sample return, Connolly told Space.com. “It has always been thought of as the Holy Grail of Mars robotic missions, and has been studied extensively now for five decades.”

Over those decades, MSR has also grown more complex, Connolly said. The original 1970’s concepts did not address the most recent requirements for planetary protection or the need for carefully selected samples.

“The growth of the MSR requirements set has naturally increased the complexity and cost at each iteration of the MSR mission concept until we reached the current design of a multi-launch, multi-spacecraft, multi-sample-handoff mission,” said Connolly.

Indeed, over recent years, multiple reviews of the MSR project by independent groups have flagged MSR sticker shock.

A last estimate was about $11 billion, with samples being returned to Earth in 2040, deemed by NASA itself as too costly and not being accomplished within an acceptable time frame.

Last year, yet another appraisal group ended up finding it feasible to return Mars samples as early as 2035 for a cost of some $8 billion.

Risk reduction

“Our understanding of Mars has gotten to the point that the questions we’re asking can best be addressed with returned samples,” said Bruce Jakosky, a senior research scientist and professor emeritus at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado Boulder.

“To decide not to return them, or to put it off to an indefinite future time with human missions would be to take a major step back in exploring the solar system and the universe and in continuing to develop our scientific understanding of the world around us,” Jakosky said.

Returning samples from Mars will enable “risk reduction” for human missions, Jakosky added. It would allow us to determine the risk to human health from Martian dust and from chemicals that might be present in the dust that could be harmful, he added, such as toxic perchlorates that have been previously identified on Mars.

Jakosky also emphasized that returning Mars samples to Earth would resolve technical problems in advance of sending humans. “It would demonstrate the first round-trip travel to Mars,” he said, “and it would allow us to solve important problems in planetary protection so that we don’t put the Earth at risk from possible Martian microbes.”

Of like mind is John Rummel, a former and founding chair of the panel on planetary protection of the COSPAR, an international confab of experts. He previously worked at NASA Headquarters (1986 to 1993 and 1998 to 2008) as the space agency’s senior scientist for astrobiology and as NASA’s Planetary Protection Officer.

“There is much we would like to know about the environment of Mars — dust, for example — before bathing people in it. Mars Sample Return is one way of getting that information, while proving we can do a safe round-trip. Doing something similar with a crew in the loop could provide for a faster progression to a safe stay on Mars — but safety needs to be a strong consideration for both the crew and their eventual return to Earth,” said Rummel.

Forward thinking

“The Mars dream is back,” views Robert Zubrin, founder of the Mars Society. He views the MSR cancellation differently, attaching his forward thinking vision to Elon Musk’s still-in-the-works SpaceX Starship launch system.

Zubrin envisions initial use of lots of robotic Mars scouts, then a robotic expedition, followed by humans to Mars.

“I think that’s possible, but would require total focus by NASA, SpaceX, Musk, and the Trump administration,” Zubrin said. That said, however, he contends the Trump budget for NASA as it now stands is already moving to wreck the first two stages of the plan by trying to wreck NASA’s Mars Exploration Program.

“They need to change course,” Zubrin advised. “If they do, a wave of robotic scouts in 2028, a robotic expedition in 2031 followed by a human mission in 2033 could still be pulled off,” he said.

Underlying rationale

RELATED STORIES:

For Jakosky, he recognizes that “science” is not the only reason to send humans to Mars.

“NASA also identifies national posture and inspiration as compelling means. But all of these fall apart if we end up sending people as a publicity stunt, to just to what has been called ‘flags and footprints.’ The underlying rationale for sending people has to be compelling enough to justify the risk to those people and the cost of the missions,” Jakosky said.

Science can provide much of that rationale, concludes Jakosky. “We have the opportunity today to implement the science in a way that makes sense from a programmatic, budgetary, and risk perspective. And isn’t that what space exploration is all about?”