As space agencies plan for future crewed missions to Mars, with NASA hoping to have humans step foot on the Red Planet as soon as the 2030s, scientists warn that astronauts themselves could be carrying a threat to these missions.

This threat may very well live within their bodies.

New research using simulated Mars conditions — such as the planet’s lack of water, harsh ultraviolet radiation and exposure to toxic salts — suggests four strains of bacteria that can be carried in the human gut may not only survive in Martian soil, or “regolith,” but, under the right conditions, thrive.

Worryingly, these bacteria — including Burkholderia cepacia, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Serratia marcescens — have the potential to cause disease in humans. For instance, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says that even though B. cepacia can cause wildly varying symptoms, exposure to the bacteria can result in serious respiratory infections and is already resistant to common antibiotics.

“We looked at four different bacterial species, which are associated with humans and had not really been investigated in a Mars-like environment,” research team member and German Aerospace Center scientist, Tommaso Zaccaria, told Space.com. “We were able to see that these species of bacteria were able to survive, to an extent, in certain Mars conditions — under desiccation [loss of moisture], UV radiation and in Mars’ atmosphere.”

Related: Life on Mars could have thrived near active volcanoes and an ancient mile-deep lake

The bacteria’s survival surprised the team. Particularly, the researchers weren’t expecting how the bacteria took to toxic Martian regolith, which was simulated here on Earth to represent global conditions on the Red Planet rather than a specific area of the planet.

“We thought that the regolith would actually have more of a toxic effect on the bacteria and that it would limit the growth in such a way,” Zaccaria said. “We didn’t think it would completely kill them all, but we thought it would be more limiting. Instead, it seemed regolith was supplementing the bacteria’s growth.”

The team also found that not only can the bacteria survive for several days, with P. aeruginosa lasting for a period of up to 21 days, but in certain conditions, they could prosper in Martian soil. These conditions included access to liquid water and protection from UV light — exactly the conditions human habitats on Mars will have to establish for astronaut survival.

Zaccaria added that this means missions to Mars will have to take medical precautions, such as carrying extra antibiotics, to protect humans on the Red Planet from bacterial threats brought from home.

Skewing the hunt for life on Mars

Despite the survival of the bacteria in Mars-like conditions, the dependence on very specific conditions to survive means it is unlikely that the organisms will colonize the Red Planet after being carried from Earth. “Growth would be very limited,” Zaccaria assured.

That doesn’t mean there isn’t cause for concern, however.

“We still think it’s quite important to protect Mars, and we want to highlight the fact that there should be some mission planning to take into account also these kinds of bacteria,” Zaccaria said. “We don’t want to contaminate Mars with human-related bacteria.”

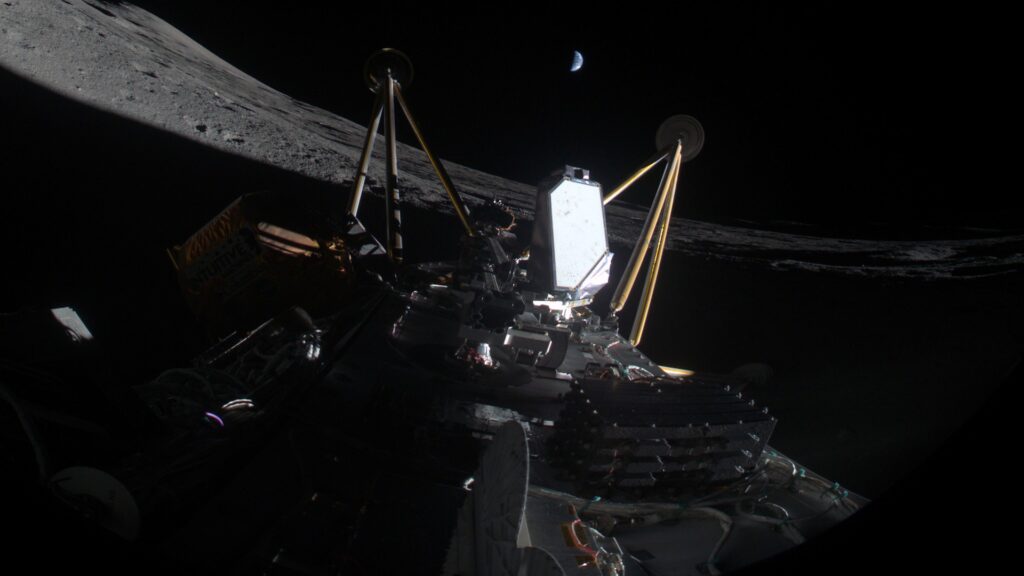

Currently, NASA rovers Curiosity and Perseverance are exploring ancient, dried lake beds on Mars to search for signs that simple life, like bacteria, could have once existed on the presently arid world.

This new research suggests, however, that if humans were to explore regions like this in person, they may carry unwanted bacteria with them and potentially cause contamination. This bacteria could also change under the conditions of Mars, making it hard to identify as having come from Earth. And this could result in some confusion that prevents us from determining whether signs of life discovered on Mars originated on the Red Planet or hitched a ride from our own home.

“If there would be some interesting astrobiological interest on a specific location of Mars, perhaps only easily sterilized robotic missions less contained with human bacteria should be allowed to go there,” Zaccaria said. “This could involve classifying certain areas of Mars as regions like national parks that we have here on Earth.”

RELATED STORIES:

Zaccaria added that, because the human immune system functions differently in the microgravity of space, he can’t currently predict the precise effect the four studied bacteria would have on human health on Mars. This is an investigation that he and his colleagues at the German Aerospace Center will undertake in the future.

Additionally, the researchers will investigate how other bacteria deal with Mars-like conditions.

“Perhaps some bacteria would be more tolerant to the conditions on Mars, and they will resist for longer periods of time, or maybe they’re less resistant,” Zaccaria concluded. “It will be interesting to evaluate other types of bacteria which are human-associated, which do not necessarily cause disease, but can be transported by the human microbiome either on the skin or inside the human body, to Mars.”

The team’s research was published in January in the journal Astrobiology.