The largest asteroid to zoom past Earth this year will do so on March 21, NASA says.

Astronomers will get a valuable opportunity to observe a space rock up close as asteroid 2001 FO32 swoops past our home planet on March 21, but the rock won’t come closer than 1.25 million miles (2 million kilometers), NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory announced today (March 11) in a statement.

“There is no threat of a collision with our planet now or for centuries to come,” the statement read.

Related: Scientists prepare for their last good look at asteroid Apophis before 2029 flyby

“We know the orbital path of 2001 FO32 around the sun very accurately, since it was discovered 20 years ago and has been tracked ever since,” Paul Chodas, director of the Center for Near Earth Object Studies (CNEOS), which is managed by JPL, said in the same statement. “There is no chance the asteroid will get any closer to Earth than 1.25 million miles.”

The asteroid, which is estimated to be 1,300 feet to 2,230 feet (440 to 680 meters) wide, will zoom past us at a whopping 77,000 mph (124,00 kph), which is faster than most asteroids travel near Earth. Its unusual speed is due to its elongated and highly inclined orbit around the sun, according to JPL. As the rock nears the inner solar system, it picks up speed before whipping back around toward deep space before turning back towards the sun, orbiting once every 810 days.

The rock is deemed a “potentially hazardous asteroid,” or PHA, by the CNEOS. The CNEOS monitors PHAs like 2001 FO32 using ground-based radar and telescopes, tracking their movement in case they get close enough to Earth to pose an impact risk.

Related: Huge asteroid Apophis revealed in photos

While the asteroid orbits the sun once about every 2.25 years, 2001 FO32 won’t come this close to our planet again until 2052, when it will pass by at 1.75 million miles (2.8 million km), according to JPL.

Although the upcoming “close” pass doesn’t pose a risk for those of us living on planet Earth, the flyby does provide an opportunity for astronomers to get a good look at 2001 FO32.

The proximity will allow astronomers to better observe the asteroid’s size and brightness and give them a better idea of its composition, essentially doing “geology with a telescope,” Vishnu Reddy, an associate professor at the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory in Tucson, said in the same JPL statement.

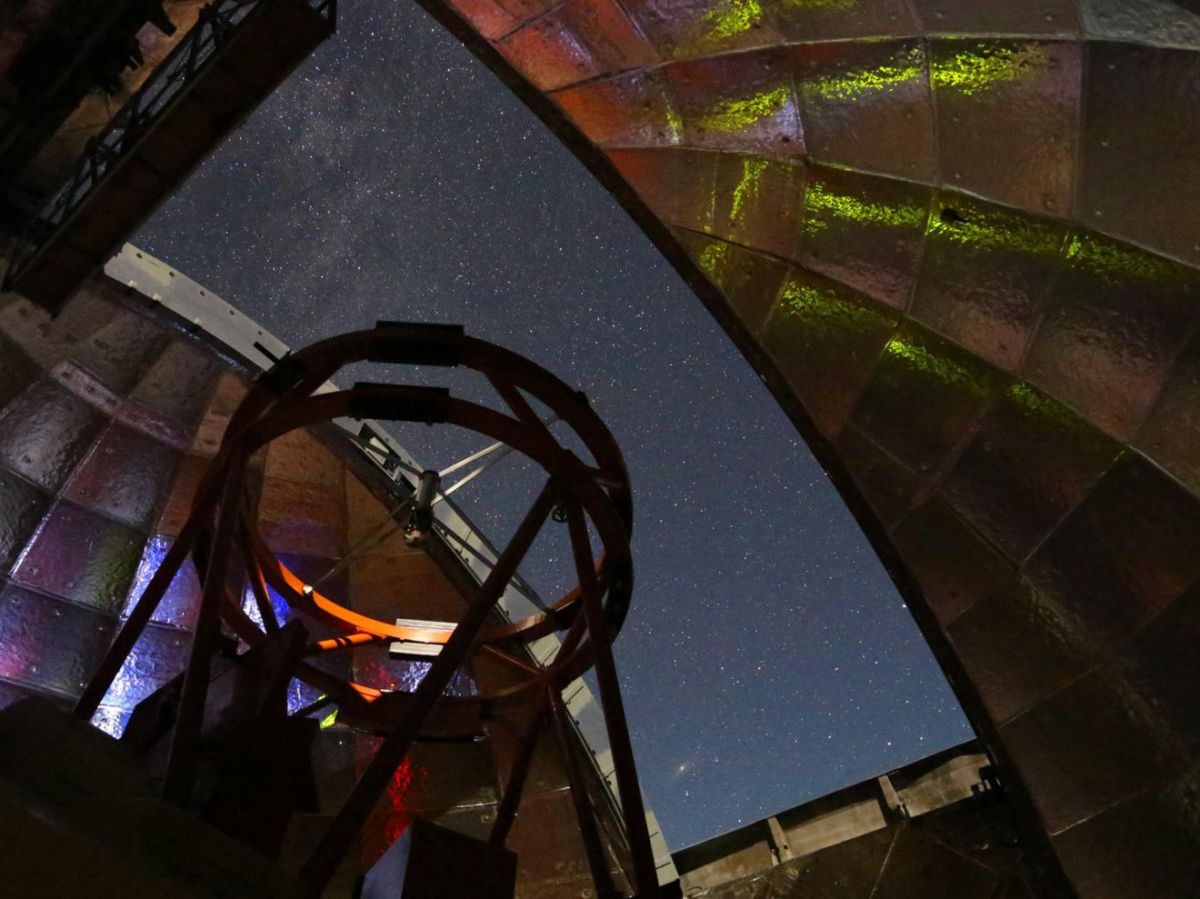

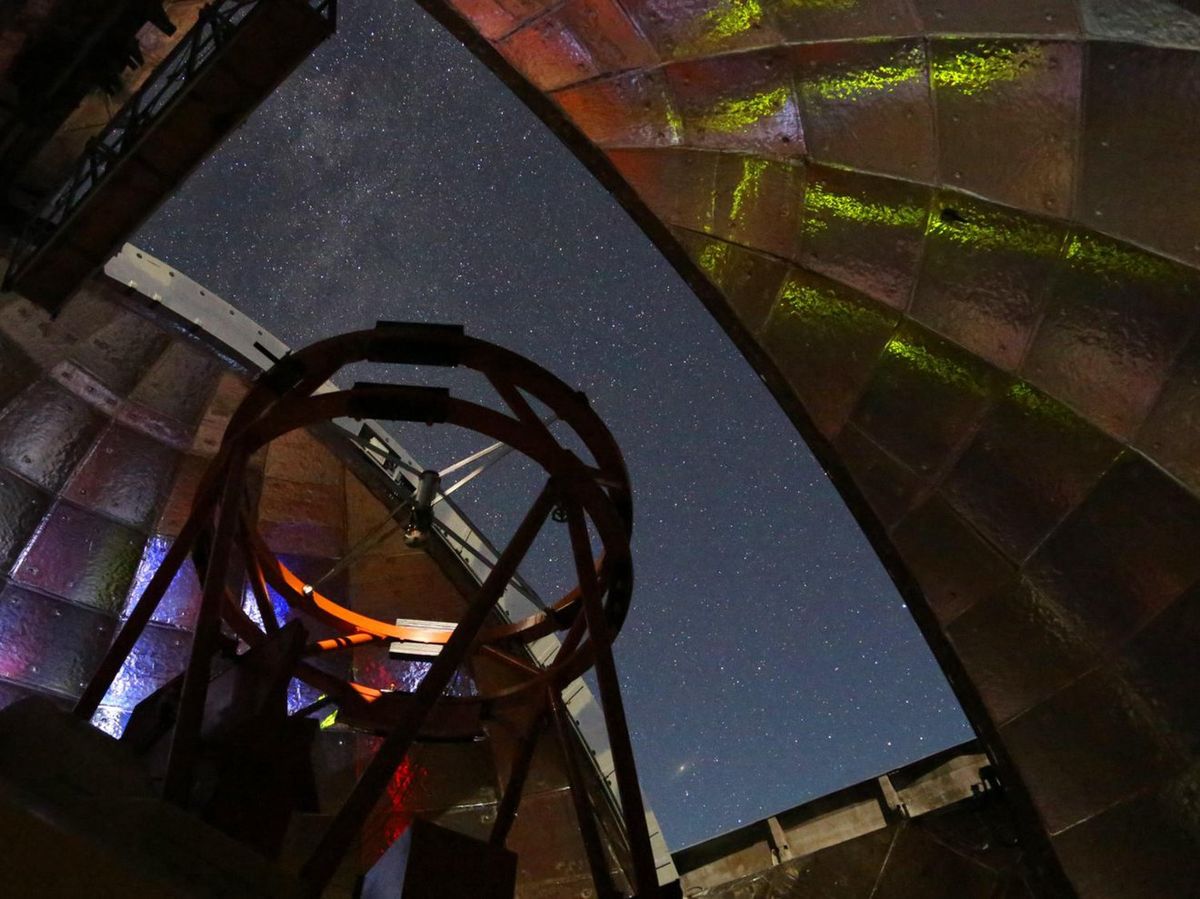

Now, while professional astronomers are planning their observations for the flyby with telescopes like NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility (IRTF) in Hawaii, “amateur astronomers in the Southern Hemisphere and at low northern latitudes should be able to see this asteroid using moderate-size telescopes with apertures of at least 8 inches in the nights leading up to closest approach, but they will probably need star charts to find it,” Chodas said.

Email Chelsea Gohd at cgohd@space.com or follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.