Two prominent space advocacy groups are cheering the new generation of Mars explorers.

While NASA’s newly landed Perseverance rover is getting the lion’s share of coverage in the United States, both the United Arab Emirates and China also entered Mars orbit successfully in February.

The Planetary Society’s CEO Bill Nye expressed optimism that China’s Tianwen-1 mission might open up opportunities for collaboration between the country and the United States, which have had tricky international relations for decades over matters ranging from intellectual property to security concerns and human rights. Notably, Tianwen-1 is a planned triple mission — an orbiter, lander and rover — that hopes to touch down on Mars this spring.

Related: The boldest Mars missions in history

“Here is an example where the collaboration is going to be between scientists,” Nye told Space.com. “Yes, I understand the concern of the military. The technology, they don’t want to transfer it without [addressing] pirating, abuse of intellectual property rights and so on. But just that people are talking — that scientists in China and scientists in the West are talking about Mars — is really significant.”

The Mars Society’s president, Robert Zubrin, called the Chinese effort “a remarkable thing” after other recent achievements by the program, including the first lunar farside landing in 2019 and a lunar sample return mission in 2020. “It’s now merging into its rightful place with the world’s leading countries, and certainly this will encourage a lot of Chinese to become scientists and engineers. I think that’s why they did it,” Zubrin told Space.com.

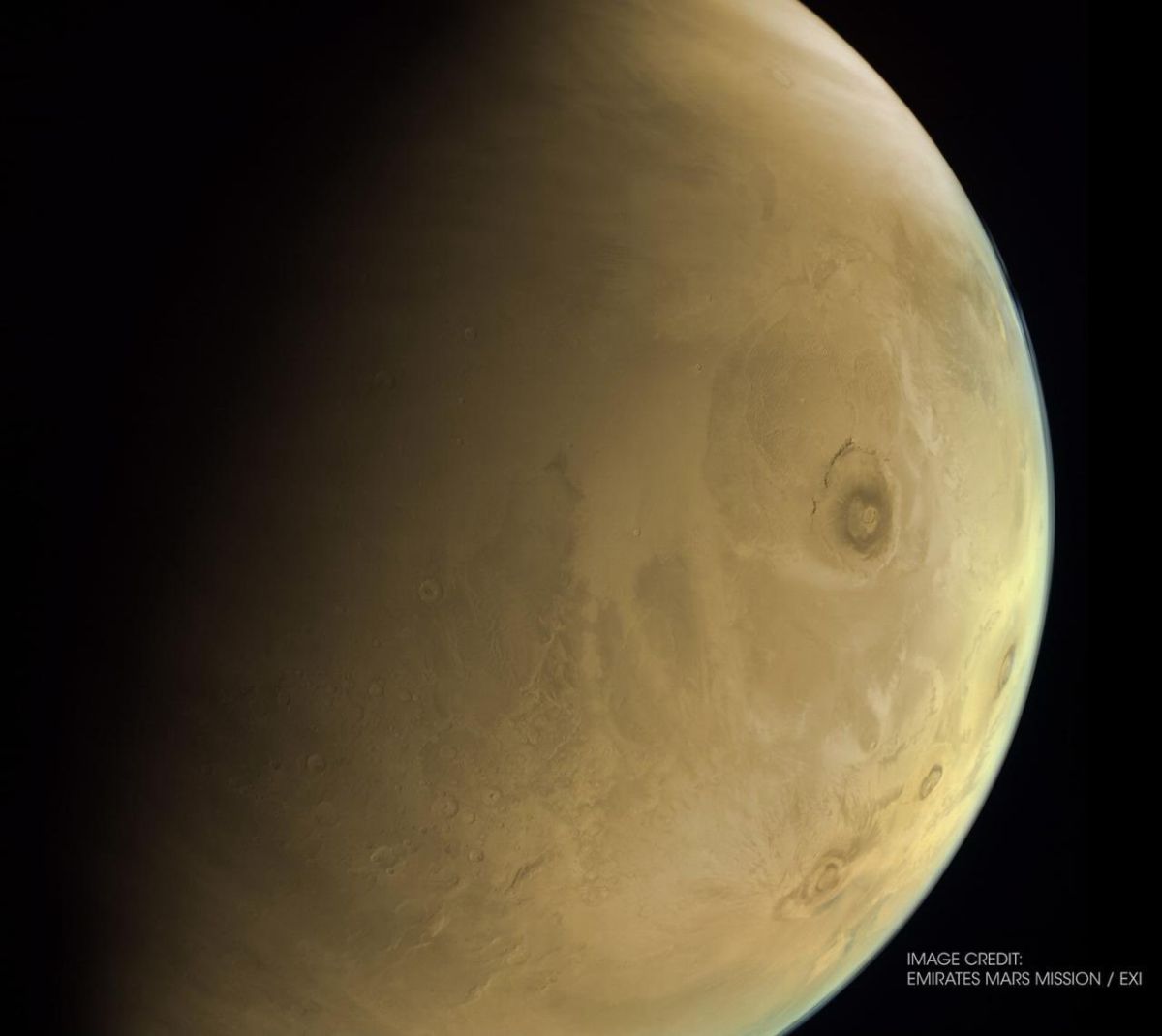

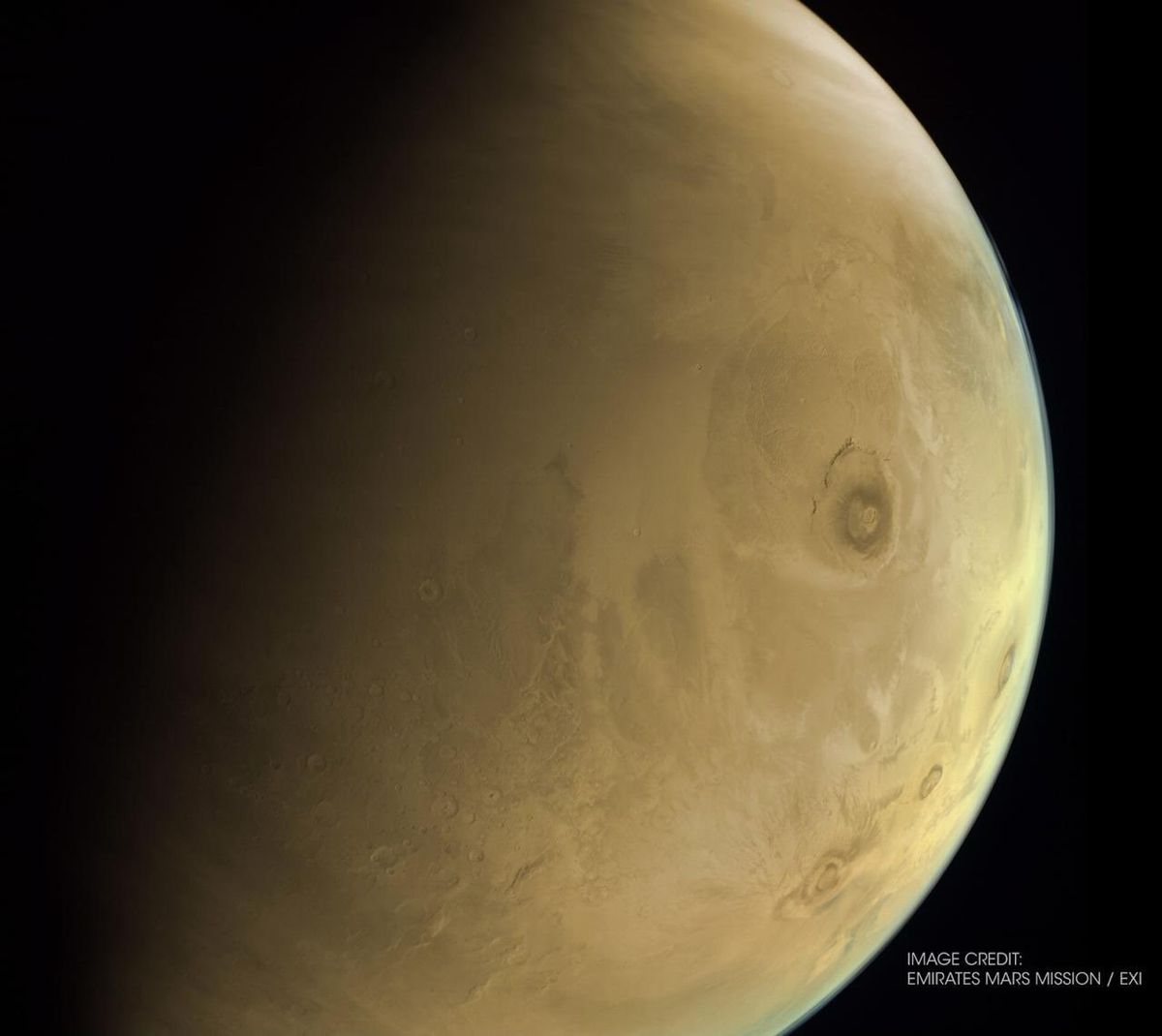

The UAE’s Hope mission is also attracting attention for its emphasis on bringing science and engineering expertise to the tiny Arab country, which is investing heavily in education in preparation for a post-oil economy. Nye said that the old joke about the complication of rocket science applies in Hope’s case, calling the achievement “not trivial” because the UAE made it to orbit on the first try. “It’s not easy, man. And they done it. It’s really fantastic,” he said.

The UAE, China and previously India (whose Mars Orbiter Mission arrived at the Red Planet in 2014) represent a new generation of planetary explorers. Traditionally, Mars has been the province of large space agencies from the United States, the Soviet Union and Europe.

But changes in spacecraft technology such as miniaturization and cheaper rockets are enabling smaller space agencies to shoot much further into space than ever before. Satellites are smaller and more powerful thanks to advances in computing; the first-ever cubesats reached Mars in 2018 with NASA’s InSight mission. Rockets are also lighter and cheaper, due to the number of companies and countries manufacturing them in the past decade and ongoing improvements in metrics such as mass and materials.

Both Nye and Zubrin pointed to the context in which these newer space missions are happening, too. When NASA and the Soviet Union were slinging early missions to Mars in the 1960s, the two countries were competing in a political- and military-driven “space race” for dominance, which also fueled much of the push behind the Apollo moon landings between 1969 and 1972. While national pride is still on the line with these newer Mars missions, Nye and Zubrin acknowledged, they see a new emphasis on bringing the softer benefits of science and engineering to the public with each successful launch.

“What we’re striving for here is not dominance, but who can achieve the most expansive human knowledge,” Zubrin said, adding that as each smaller country makes it to Mars, it inspires other countries to go. “If you were to say in Chile right now, ‘Why don’t you do a Mars mission?’ it seems more possible because the UAE did it.”

The likelihood of these missions learning new things abut the cosmos is also exciting. “They’re doing it because it brings out the best in people, it brings out the best in their scientists and engineers and inspires the country, and you’re going to make discoveries that you didn’t anticipate,” Nye said of the new countries’ achievements. “You’re going to learn more about the cosmos. Then there’s the practical things — predicting the [Martian] weather and [testing] communication.”

Both the Mars Society and the Planetary Society advocate for space regularly among politicians and the American public, looking to gain more support for their individual mandates. The Mars Society, established in 1998, calls for exploring Mars and “creating a permanent human presence on the Red Planet,” according to its website. The Planetary Society blends in goals of space technology and giving individual humans worldwide a voice in planning through a mandate of “empowering the world’s citizens to advance space science and exploration.”

The Planetary Society’s short-term goals on Mars includes supporting ongoing planning for the sample-return mission and parsing early results from the NASA Ingenuity helicopter, which made the first-ever powered flights on Mars this year.

Related: Mars helicopter Ingenuity spots Perseverance rover from the air (photo)

“We have a helicopter sitting on Mars, everybody, this is not trivial,” Nye pointed out. Although he spoke with Space.com before the landmark flights, he noted the importance of the sorties and the project as a whole.

Adding a helicopter capability will be “really extraordinary” not only for the sheer value of flying, but also to give valuable context to geologists. “Rather than relying on orbiting cameras — which are extraordinary and give you amazing detail of the Martian surface — [you will] be this close to [the surface] with this drone … Come on. It’s just going to be fantastic.”

Zubrin added that he wouldn’t be surprised if SpaceX’s Elon Musk brings people to Mars in the near future. That said, he isn’t quite in agreement with Musk’s methodology, although they do share some elements such as using Mars resources in-situ for spacecraft fuel.

Simply put, Zubrin’s “Mars Direct” mission calls for an Earth Return Vehicle (ERV) that launches uncrewed to Mars and arrives at the Red Planet six months later; subsequently, a new ERV and astronaut habitat would fly to the Red Planet every 26 months to bring people and supplies to Mars. Musk’s Starship, by contrast, will zoom off to Mars by itself and then lift off itself at the end of the mission; there are no plans for a separate Mars base and Musk hopes to go quickly, as soon as 2024.

Zubrin says he doesn’t feel Starship is suited for a Mars takeoff due to its sheer size, but he did express admiration for Musk’s vision; the two men met early last year in Boca Chica, Texas, nearby where Starships typically launch. Zubrin says his impression is Musk wants to “get to it” with Mars exploration rather than waiting for a space agency like NASA to support him. “He is purpose-driven and he doesn’t do anything in order to please someone else,” Zubrin said.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.