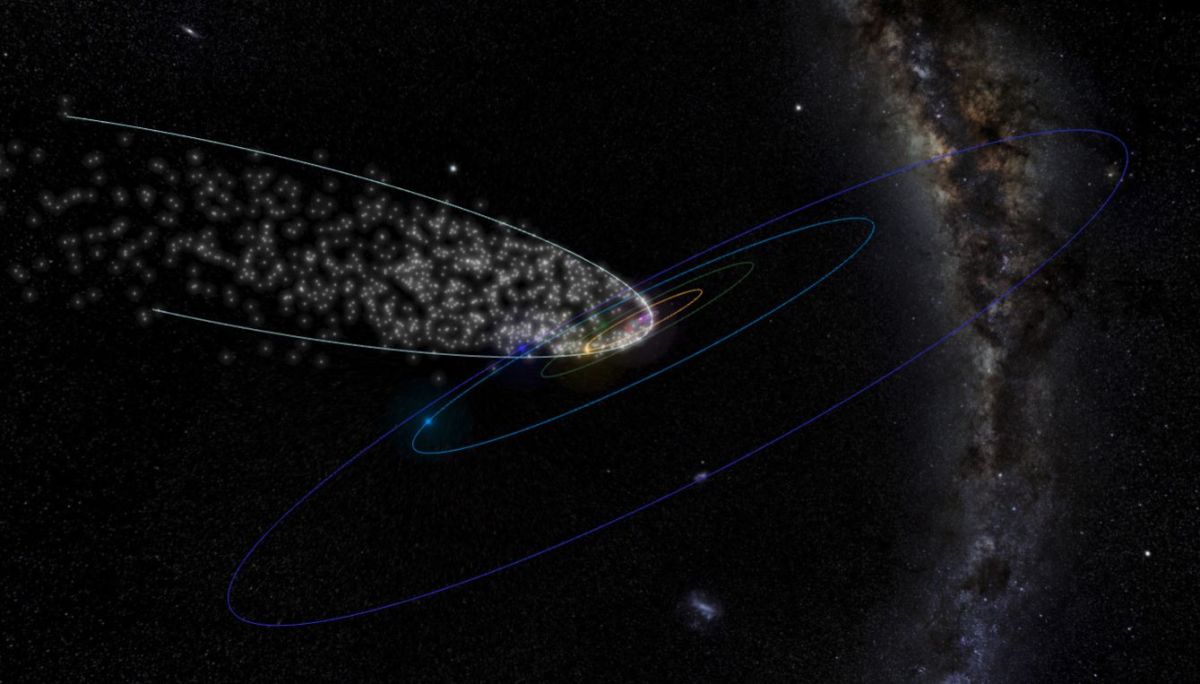

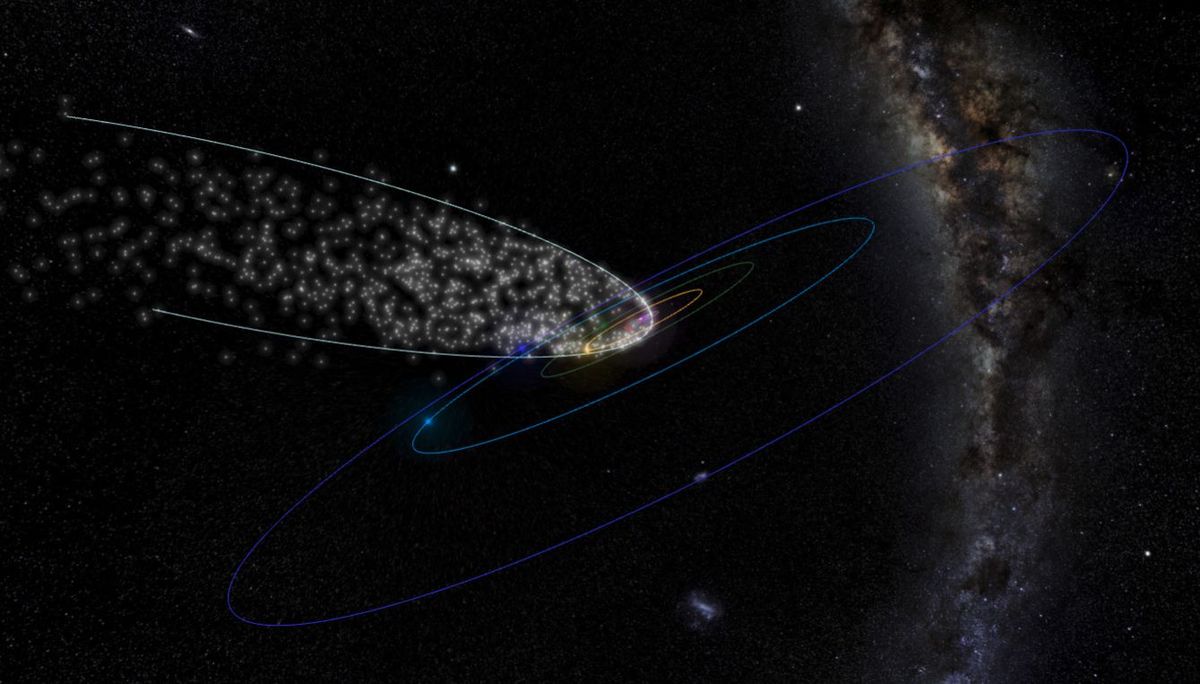

Meteor showers are the dazzling result of cometary debris building up along well-worn paths through the solar system, then burning up in Earth’s atmosphere as our planet crosses that dust trail.

It’s hard to call a path well-worn when something passes by only once every 3,967 years. But it turns out that type of long-period comet can still be tied to a specific meteor shower, as scientists have done with Comet C/2002 Y1 Juels-Holvorcem and the UY Lyncids shower. The research that connected the long haul ice ball and the shower triples the number of celestial displays that scientists have tied to specific comets that take more than 250 years to orbit the sun.

“Until recently, we only knew five long-period comets to be parent bodies to one of our meteor showers,” Peter Jenniskens, a meteor astronomer at the SETI Institute and the lead author of the new research, said in a statement. “But now we identified nine more, and perhaps as many as 15.”

Related: How to see the best meteor showers of 2021

For some perspective, Comet C/2002 Y1 Juels-Holvorcem most recently made a close approach of the sun in 2003 — which means its last such visit was around 2,000 B.C., when Egypt’s Great Pyramids were just a few hundred years old, and its next pass of the sun won’t occur until nearly the year 6,000.

Typically, a shorter orbit means a comet retraces its path more regularly, scattering more rubble that can become more “shooting stars” when Earth plows through the debris. That means it’s difficult for skywatchers to notice meteor showers caused by comets with orbits beyond about 250 years or so.

The best known long-period comet that triggers a meteor shower is comet C/1861 G1 Thatcher, which causes the April Lyrid meteor shower. Other long-period comets’ showers are less dramatic, even those scientists had previously identified, like the Aurigids (debris from C/1911 N1 Kiess) and the Leonis Minorids (from C/1739 K1 Zanotti).

The scientists behind the new study wanted to find more such connections, so they turned to a program called Cameras for Allsky Meteor Surveillance (CAMS), which includes observation stations across the United States and around the globe, including in New Zealand, Namibia, Chile and the United Arab Emirates — networks totalling more than 500 individual cameras all told, all watching for meteors.

“These are the shooting stars you see with the naked eye,” Jenniskens said. “By tracing their approach direction, these maps show the sky and the universe around us in a very different light.”

Related: Amazing photos of Comet NEOWISE from the Earth and space

Looking at such huge amounts of meteor sightings, scientists can pick out subtle meteor showers based on tracking only a few shooting stars to similar origin points in the sky, called radiants. So astronomers combined that analysis of a decade of observations with NASA’s database of comets and their orbits.

The scientists found at least nine new matches between meteor showers and long-period comets, and identified another six potential matches. The research tracks down the comets responsible for esoteric meteor showers, like December’s sigma Virginids and July’s Pegasids, caused by debris from C/1846 J1 Brorsen and C/1979 Y1 Bradfield respectively.

Most of the comets in the research swing past the sun every 400 to 800 years or so, a quite respectable calendar. Three comets joined Juels-Holvorcem is a bit of an outlier with orbits longer than 1,000 years. Scientists have tied a few other long-period comets to specific meteor showers, but can’t quite pin down their orbital periods.

Among the meteor showers studied, the researchers noticed an intriguing trend: Displays from long-period comets tend to last several days, and the radiant appears to move like a smudge on the sky. The scientists on the new research think the effect may be caused by a comet’s orbit shifting between loops, so that the rubble fields don’t align as cleanly as they do for short-period comets.

“This was a surprise to me,” Jenniskens said. “It probably means that these comets returned to the solar system many times in the past, while their orbits gradually changed over time.”

The research is described in a paper that will be published this autumn by the journal Icarus.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or fo