Humanity’s return to the moon could open up new windows on the universe.

NASA is working to establish a permanent human presence on and around the moon by the end of the 2020s, via a program known as Artemis. That presence may eventually include radio telescopes on the moon’s exceptionally quiet far side — and, perhaps, even more ambitious off-Earth science facilities.

For example, a recent study makes the case for building a gravitational-wave observatory on the moon.

Hunting gravitational waves: The LIGO laser interferometer project in photos

[embedded content]

Gravitational waves are ripples in space-time created by the acceleration of massive objects. They were predicted by Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity in 1915 and first directly detected a century later, by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) consortium.

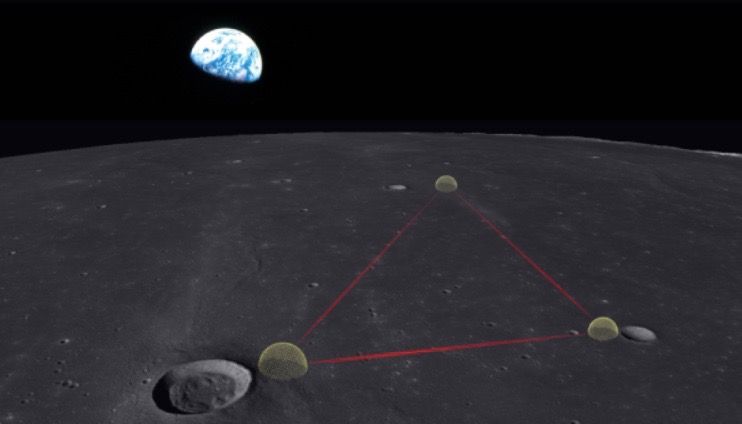

LIGO has detectors at two sites, one in Louisiana and one in Washington state. Each detector is an L-shaped structure with arms 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) long, with a laser at the center of the array. The laser shines light down each arm, and mirrors reflect the light back. If the light from one arm comes back a bit late, it’s evidence of a possible gravitational-wave-induced distortion.

The LIGO team has detected dozens of gravitational-wave events to date, most of them caused by mergers between two black holes. But this is exacting work, and our noisy, active Earth makes spotting signals tough.

The moon, on the other hand, is an exceptionally quiet place, the new study notes.

“The moon offers an ideal backdrop for the ultimate gravitational wave observatory, since it lacks an atmosphere and noticeable seismic noise, which we must mitigate at great cost for laser interferometers on Earth,” co-author Avi Loeb, an astronomer at Harvard University, said in a statement.

“A lunar observatory would provide unprecedented sensitivity for discovering sources that we do not anticipate and that could inform us of new physics,” Loeb said. “GLOC could be the jewel in the crown of science on the surface of the moon.”

Lunar timeline: Humanity’s explorations of the moon

“GLOC” is short for the Gravitational-wave Lunar Observatory for Cosmology, the name Loeb and study lead author Karan Jani propose for the moon facility. GLOC would be huge compared to LIGO and other detectors on Earth, featuring arms 25 miles (40 km) long. And it would be incredibly sensitive, capable of spotting gravitational-wave events in nearly 70% of the observable volume of the universe, the researchers calculated.

“By tapping into the natural conditions on the moon, we showed that one of the most challenging spectrum of gravitational waves can be measured better from the lunar surface, which so far seems impossible from Earth or space,” Jani, an astrophysicist at Vanderbilt University in Tennessee, said in the same statement.

GLOC is just an idea at the moment, but Jani and Loeb said they hope to develop a pathfinder mission on the moon that would test GLOC’s required technologies in the coming years. And if GLOC or something like it does end up getting built, it will pay scientific dividends for decades to come, the researchers said.

“Unlike space missions that last only a few years, the great investment benefit of GLOC is it establishes a permanent base on the moon from where we can study the universe for generations, quite literally the entirety of this century,” Jani said in the statement.

The new study was published last month in the Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. You can read it for free at the online preprint site arXiv.org.

Mike Wall is the author of “Out There” (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.