Scientists are using infrared to better explore Jupiter’s moon Ganymede, the largest moon in our solar system.

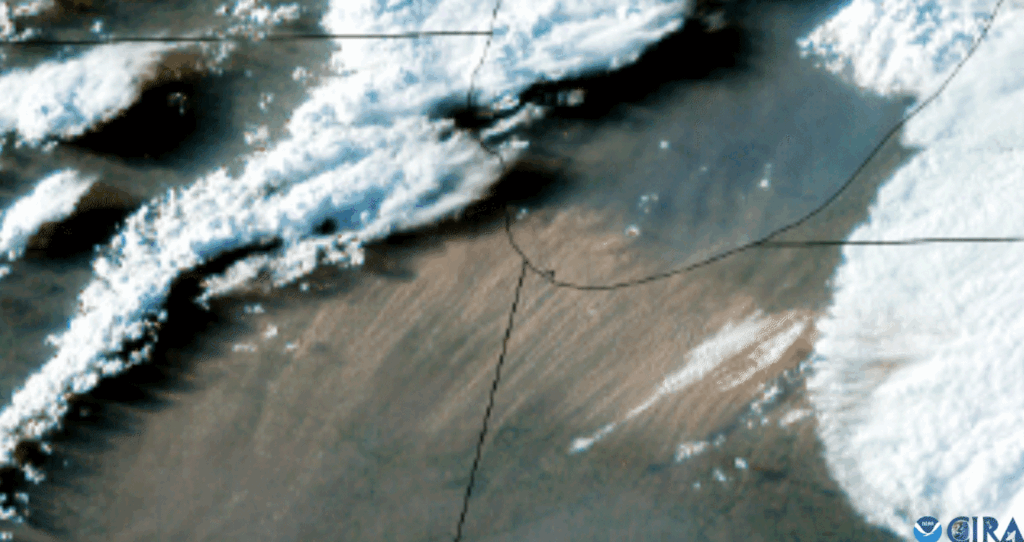

As we mark 10 years since NASA’s Juno mission launched from Earth, the craft has delivered stunning images from its orbit around Jupiter, including new infrared views of Ganymede captured during its latest flyby of the Jovian moon on July 20.

Using Juno’s Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) instrument, which detects in infrared light that is not visible to the human eye, the Juno science team has created a new infrared map of Ganymede, which they hope will help them to better understand the Jupiter moon’s ice crust and the ocean lurking beneath, according to NASA.

“Ganymede is larger than the planet Mercury, but just about everything we explore on this mission to Jupiter is on a monumental scale,” Juno Principal Investigator Scott Bolton, a researcher at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, said in a NASA statement. “The infrared and other data collected by Juno during the flyby contain fundamental clues for understanding the evolution of Jupiter’s 79 moons from the time of their formation to today.”

In photos: NASA’s Juno Mission to Jupiter

During Juno’s most recent encounter with Ganymede, which followed a much closer flyby on June 7, the spacecraft swung within 31,136 miles (50,109 kilometers) of Ganymede’s surface.

With this close pass, Juno’s JIRAM instrument was able to see Ganymede’s north polar region for the first time. The instrument also collected data about the different compositions of material at both low and high altitudes on the alien moon, according to the statement.

The data that Juno collected during this flyby adds to its previous close encounters as well as observations by previous probes like NASA’s Voyager mission as well as the agency’s crafts Galileo, New Horizons and Cassini. By observing the moon in infrared, the team was able to learn more about what really makes up Ganymede to better understand not just this moon but worlds like it as well.

“We found Ganymede’s high latitudes dominated by water ice, with fine grain size, which is the result of the intense bombardment of charged particles,” Alessandro Mura, a Juno co-investigator from the National Institute for Astrophysics in Rome, said in the same statement.

“Conversely, low latitudes are shielded by the moon’s magnetic field and contain more of its original chemical composition, most notably of non-water-ice constituents such as salts and organics,” Mura added. “It is extremely important to characterize the unique properties of these icy regions to better understand the space-weathering processes that the surface undergoes.”

As Juno continues to explore the entire Jovian system — NASA has extended Juno’s mission through September 2025 so that the probe can explore Jupiter’s moons and rings — other upcoming space missions could catch their own views of the large moon. For example, the European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) mission scheduled to launch next year will study all of Jupiter’s four largest moons, known as the Galilean moons.

Email Chelsea Gohd at cgohd@space.com or follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.