As you study the night sky and the constellations, you soon begin to realize that some star patterns come in pairs.

In several cases, the brighter constellation is recognized as “major” while the smaller or dimmer constellation is designated as “minor.” We see this with two bears (Ursa) and two dogs (Canis). The star pattern known as Leo (the Lion) is so prominent that there is no need to use the “major” designation, nonetheless, there is a much smaller and dimmer constellation nearby that goes by the name Leo Minor.

Then there are the star patterns that outline similar animals but go without the “major” and “minor” designations. There are the two water snakes (Hydra and Hydrus) and two horses (Pegasus and Equuleus). The creature for which the former constellation is named possesses the unusual ability to fly, while the latter is merely a foal.

Related: Constellations of the Western zodiac

Finally, there are similar constellations that are positioned in the northern and southern halves of the sky. In such cases, “borealis” refers to the northern star group, while “australis” refers to the south. There are two triangles, and a southern fish. (The zodiacal constellation of Pisces represents two fishes, but without any reference to their positions north of the celestial equator.)

And let’s not forget the crowns.

The Northern Crown

There are two star patterns representing crowns that are visible in our current late-summer evening sky: Corona Borealis (the Northern Crown) and Corona Australis (the Southern Crown).

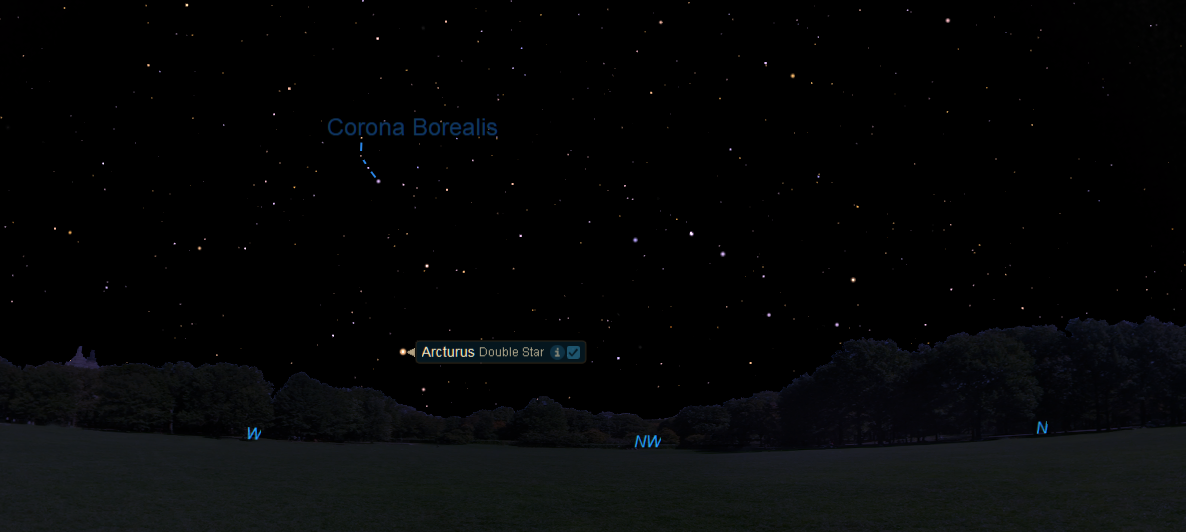

Corona Borealis is a small but graceful star pattern, just off to the east of Boötes (the Herdsman). In the sky it actually looks more like a tiara. For many years, I always enjoyed pointing out the Northern Crown to audiences at New York’s Hayden Planetarium during the month of September, commenting that it looked very much like the crown presented to the winner of the annual Miss America pageant. But since the pageant has been moved to December, I have to be a little more creative.

Nowadays, I link Corona Borealis with Boötes by pointing out that the latter star pattern looks like an ice cream cone. Start at the Big Dipper, then follow along the curve of its handle until you come to Arcturus, which marks the bottom of the cone.

As I’ve told my audiences, the cone is not actually holding ice cream but orange sorbet. We know that, because someone bit off the bottom of the cone, allowing some of this delicious concoction to dribble out — and that’s when I point to pumpkin-hued Arcturus.

I follow that up by noting that there were originally two scoops in this cone. We can see the bottom scoop embedded in the cone, but the top scoop has fallen off. That second, inverted, scoop, positioned just off to the left of the top of the cone, is Corona Borealis; an alternate rendition of the Northern Crown!

Whether you visualize it as a sorbet scoop or crown, here are a couple of other interesting facts about this beautiful little circlet of stars.

The brightest star of Corona Borealis is second-magnitude Alphecca, better known as Gemma, the jewel in the crown, perfectly placed in the middle of the bow. For positive identification, an imaginary line from Megrez, the star that joins the bowl with the handle of the Big Dipper, stretched to Alkaid, the star at the end of the handle, and then extended twice the distance between these two stars, will take you directly to the crown.

Sadly this is only a momentary formation, as the stars are moving helter-skelter in different directions. For instance, Gemma and Nusakan, a star immediately adjacent to it, have opposing motions, and in the past 75,000 years they have just about changed places.

Another rather amazing feature about the Northern Crown is that within its boundaries there is a very rich cluster of distant galaxies, referred to as a supergalaxy. It is one of the most remarkable of all such aggregations, composed of more than 400 galaxies. However, the cluster is extremely remote; estimates place it at 1.3 billion light-years away and receding from us at 13,000 miles per second (21,000 kilometers per second), or about 1/14th the velocity of light.

The Southern Crown

Corona Australis, the Southern Crown, is situated low above the southern horizon at nightfall this week, below the famous Teapot asterism of Sagittarius.

Unfortunately, this crown is positioned so low in the sky when viewed from mid-northern latitudes. More often than not this tight, striking semicircle of stars is hidden from view by low-lying haze near the horizon (its brightest stars are only of fourth magnitude). When seen from New York, it barely gets 10 degrees above the horizon. As we have mentioned before, 10 degrees is roughly the width of your fist held at arm’s length, so the southern crown never gets much higher than “one fist” above the southern horizon. You have to go to the southern U.S. or the tropics to get a really good view of it.

And in much the same way that I used Boötes with Corona Borealis, about a half a century ago the late astronomy popularizer George Lovi (1939-1993) pointed out that we could augment the Teapot with a teaspoon and lemon slice. Lovi’s teaspoon comprises stars in northern Sagittarius, while his lemon slice is an alternate rendition of Corona Australis.

The obsolete (third) crown

At this point, I think it fair to mention a third crown that once adorned some, but not all, star atlases during the late 18th century. It was conceived by the German astronomer Johann Bode in 1787 as his way of honoring Frederick the Great, the late king of Prussia who had died the previous year.

The constellation Bode created was composed of a jumble of dim stars that were taken from adjacent constellations of Andromeda, Lacerta, Cepheus, Pegasus and Cassiopeia. Known as Gloria Frederica or Frederici (the Glory of Frederick), it was an arcane, shapeless star pattern, which Bode described as a crown hovering above a sword, pen and olive branch, based on his perception of Frederick as a “hero, sage and peacemaker.”

But by the late 19th century, Gloria Frederica was all but forgotten, and in 1930, when official constellation boundaries were set, Frederici never made the cut.

Too bad! If it had survived, we might have had a version of the triple crown in the night sky.

Crown mythology

Both Corona Borealis and Australis are ancient constellations, part of Claudius Ptolemy’s (c. A.D. 87 to 150) list of 48 groupings.

Corona Borealis represents the gem-studded golden crown of Ariadne, a Cretan princess associated with mazes, who in Greek legend received the crown from Dionysus, the god of wine and fertility, upon marrying him.

The much dimmer Corona Australis, however, represented a crown of leaves that were sometimes worn by the ancients on ceremonial occasions. It has no particular story associated with it, although some write that it was another crown that Dionysus gave as a gift, this one to his mother Semele.

Think about that for a moment: Dionysus gave his future wife a magnificent jeweled crown of gold, while he gave his mom a mere crown of leaves!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers’ Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.