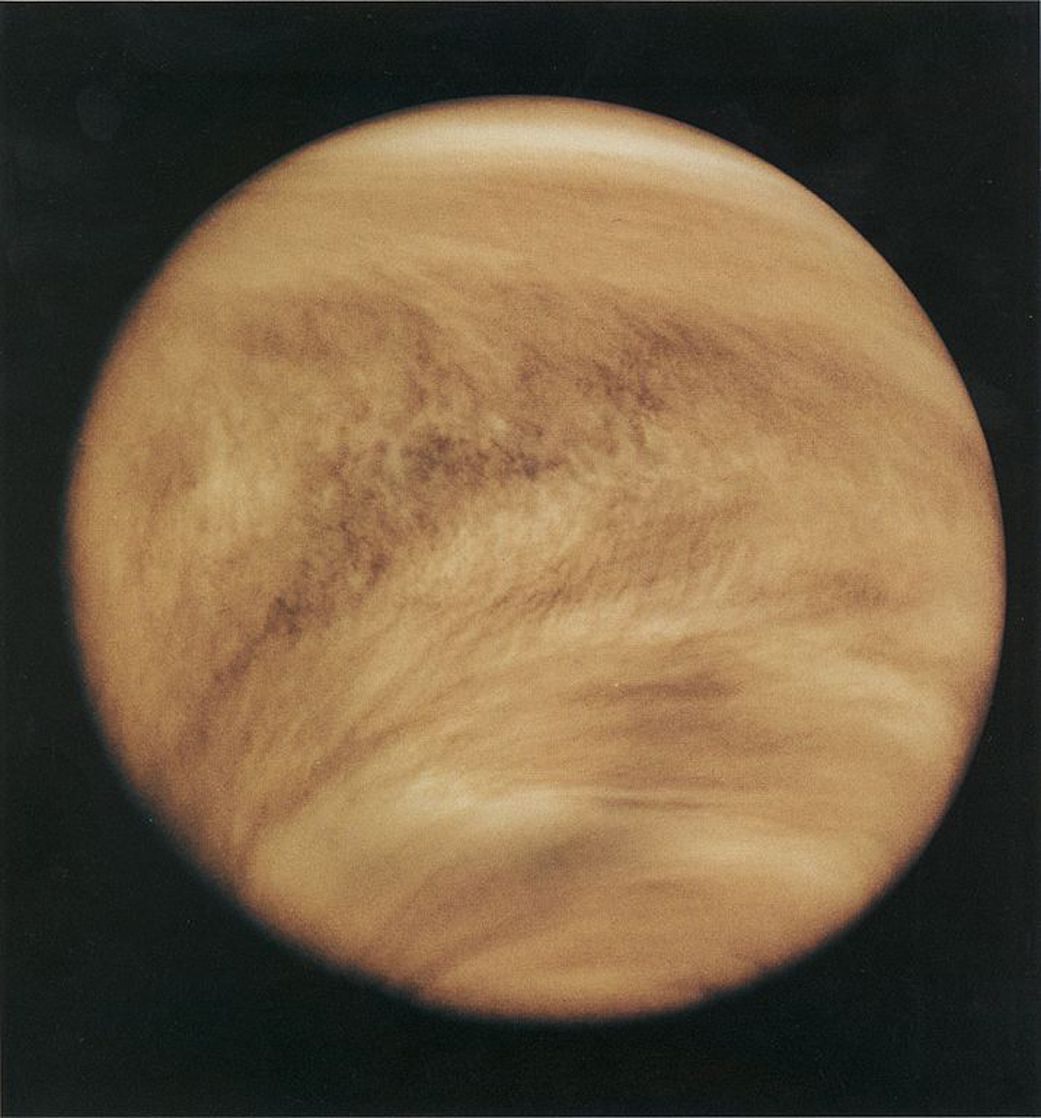

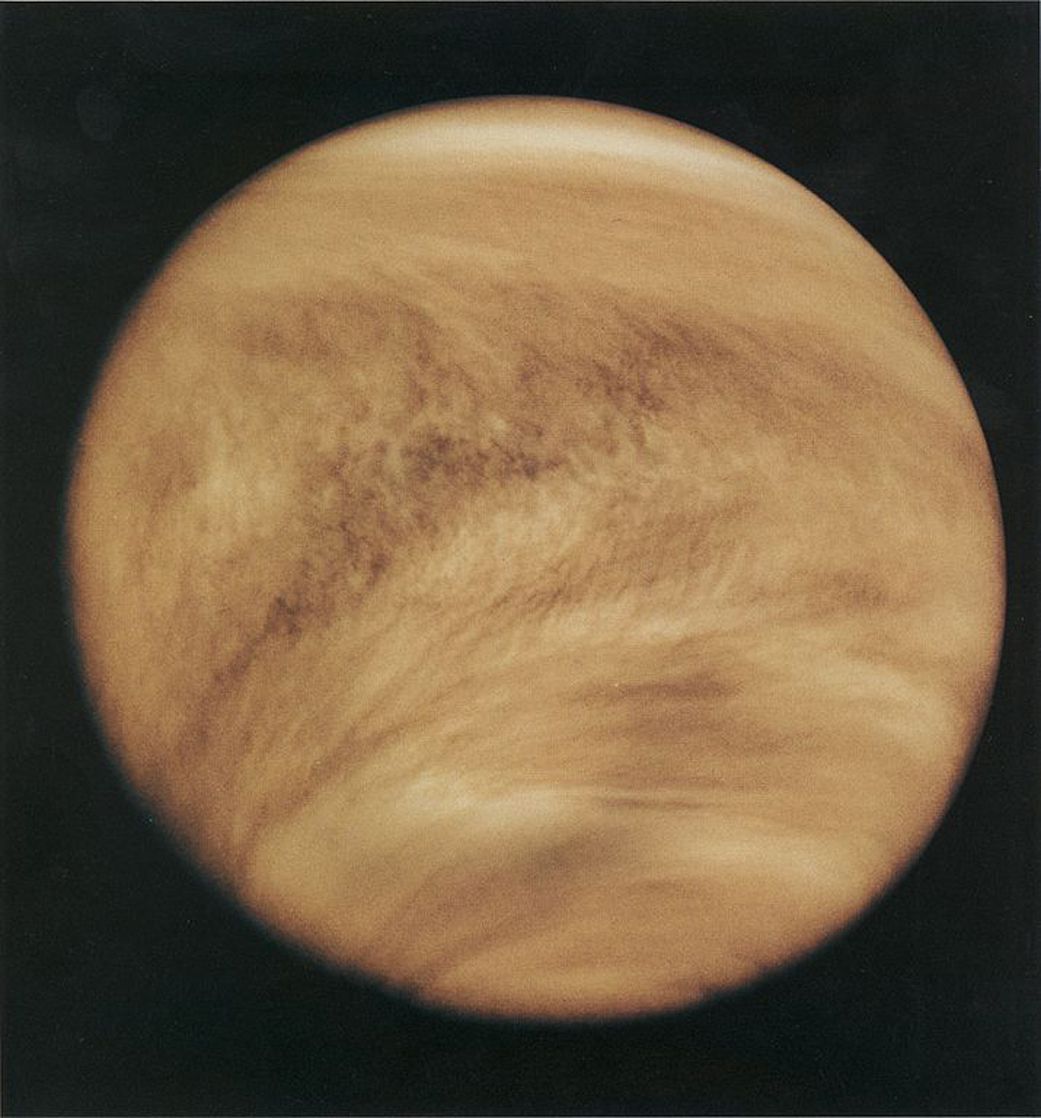

Right now, the two planets getting the most attention in our evening sky are the gas giants of the solar system: Saturn, which through even a small telescope boasts a spectacular system of rings, and Jupiter, which features a large disk crossed by gaseous bands and a retinue of four, bright satellites that change their positions relative to each other from hour to hour and night to night. Both planets are readily visible in the southwestern evening sky soon after nightfall.

And yet both of these behemoths are far inferior in brightness to the brightest planet in the sky: Venus.

Indeed, Venus is the first planet you’ll spot — maybe even before sunset, if you know where to look in the south-southwest sky. Venus is gaining altitude in the twilight, boldly showing itself off after six months of hiding behind any inconvenient obstructions near the southwestern horizon. And Venus is brightening, too, since it’s speeding toward Earth as it catches up to us in its faster orbit around the sun.

The brightest planets in October’s night sky: How to see them (and when)

A double identity

As Venus travels around the sun inside Earth’s orbit, it alternates regularly from evening to morning sky and back, spending about 9.5 months as an “evening star” and about the same length of time as a “morning star.”

Some ancient Greek astronomers actually thought these “stars” were two different celestial bodies. They named the morning object after Phosphorus, the harbinger of light, and the evening object for Hesperus, the son of Atlas. It was the Greek philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras (570-495 BC) who first realized that Phosphorus and Hesperus were one and the same object.

Such behavior was puzzling to the ancients and was not really understood until the time of Galileo. After moving to Pisa in the autumn of 1610, Galileo started observing Venus through his crude telescope. One evening, he noticed that a small slice seemed to be missing from Venus’ disk. After several more months, Venus appeared in the shape of a crescent — in other words, it seemed to display the same phases as the moon. This was a major discovery, which ultimately helped deliver a deathblow to the long-held concept of an Earth-centered universe.

Related: Photos of Venus, the mysterious planet next door

Like watching an auto race

Venus wanders only a limited distance east or west of the sun, since, like Mercury, it is an “inferior” planet (orbiting the sun more closely than Earth does). Watching its movement is akin to watching an auto race from the grandstand: all the action takes place in front of you, and it’s necessary to turn only a limited amount either way to see it. In contrast, for “superior” planets (those located in orbits beyond Earth), viewers on Earth are like the pit crews inside the racetrack, who must turn in all directions to follow the cars.

When Venus is on the opposite side of the sun from us, it appears full (or nearly so) and rather small because it is far from us. But because Venus moves with a greater velocity around the sun than Earth, it gradually gets closer and looms progressively larger in apparent size; the angle of sunlight striking it as seen from our Earthly vantage point also appears to change as well.

Ultimately, as Venus prepares to pass between Earth and the sun, it appears as a thinning crescent. And since at this point in its orbit it is nearly six times closer to us compared to when it was on the opposite side of the sun, it appears much larger to us as well.

Here, then, is a schedule of how Venus’ appearance will change during the coming weeks:

Oct. 29 — Greatest eastern elongation: Venus arrives at that point in the sky where it attains its greatest angular distance from the sun (47 degrees) and sets about 2.5 hours after sundown. (Reminder: Your clenched fist held at arm’s length covers about 10 degrees of sky.) In our solar system geometry, Venus now makes a right angle with both the sun and Earth. Venus now appears more than twice as large as it was at the end of July and is a dazzling silvery-white “half-moon” when viewed with a small telescope. In the nights that follow, it gradually becomes a fat crescent while growing ever larger as it swings around in its orbit closer to Earth.

Nov. 7 — Venus and the crescent moon will make for an eye-catching sight in the southwest sky right after sunset. Venus will shine to the upper left of the slender sliver of the moon. You should also be able to see the full globe of the moon, its darkened portion glowing with a bluish-gray hue interposed between the sunlit crescent and not much darker sky. This sight is sometimes called “the old moon in the young moon’s arms.” Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) was the first to recognize it as earthshine. That dim bluish-gray light was reflected off Earth and onto the moon. Earth’s light, of course, is reflected sunlight, so earthshine is really sunlight that’s reflected off Earth to the moon and then reflected back to Earth again. Another, similar pairing of the moon and Venus will take place on the evening of Dec. 6.

Dec. 3 — Greatest brilliance: Venus is now truly dazzling, shining at a magnitude of -4.9 and setting two hours and 45 minutes after the sun. It is so bright now that it can be seen easily with the naked eye in a deep blue, haze-free afternoon sky. It continues to approach Earth while appearing to curve back in toward the sun in our sky. In a telescope, it is now a big, beautiful crescent that grows larger and thinner with each passing night. The crescent can now be glimpsed even in steadily held binoculars. Venus now stands 38 million miles (61 million kilometers) from Earth, and its disk appears 26% illuminated and is now about 47% larger compared to just one month ago.

Related stories:

Dec. 19 — Disk 12% illuminated: The crescent of Venus continues to narrow, but because it also continues to approach Earth, it appears to greatly lengthen as well. It’s now 29 million miles (47 million km) away from us but is also in a rapid plunge down the sky toward the sun; it’s now setting two hours and 10 minutes after sunset. Compare the appearance of its two cusps. Can you make out the crescent’s “cusp extensions” — threadlike wisps of light extending beyond the crescent’s points?

Dec. 26 — Disk just 6% illuminated: It is now critical to try and locate Venus as early as possible when it is still high in the sky in a steady atmosphere. Well before sunset is best. At sunset, as seen from mid-northern latitudes, Venus stands about 15 degrees above the southwest horizon and sets about 100 minutes later. Now less than 27 million miles (43 million km) from Earth, Venus is becoming more and more aligned between us and the sun and as such is turning more and more of its dark side toward us. A week from now, it will be all but gone from the evening sky.

Jan. 8 — Inferior conjunction: Venus will finally transition from an evening to a morning star and will appear to pass between Earth and the sun on this day. By the morning of Jan. 14, Venus is emerging as a new morning “star” rising in the east-southeast at mid-dawn. After another week you should see it easily from anywhere with an open east-southeastern view, 45 minutes to an hour before sunrise.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers’ Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.