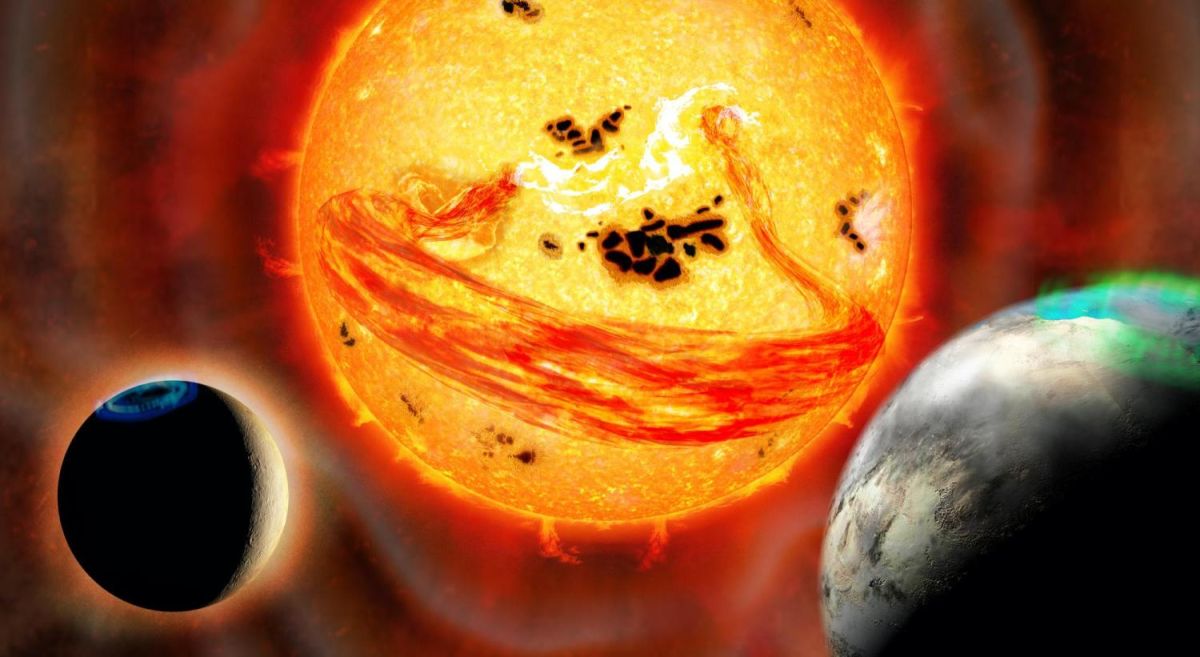

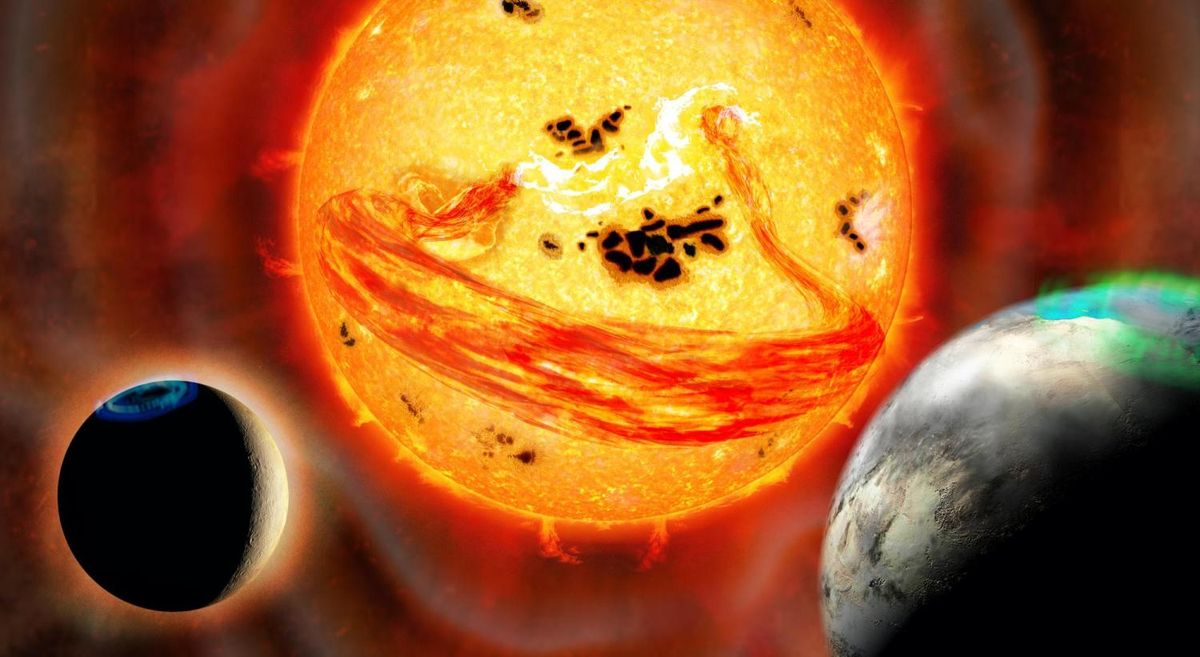

Astronomers may have, for the first time, detected a sunlike star erupting with a giant outburst 10 times larger than anything similar ever seen from our sun, a new study finds.

The new results may shed light on the effects such powerful outbursts may have had on the early Earth when life was born, and could have on modern Earth and our societies, researchers said.

Our sun often unleashes flares that can each pack as much energy as millions of hydrogen bombs exploding at the same time. Solar flares are often accompanied by giant bright tendrils of solar plasma known as filaments, which can unleash magnetic bubbles of superhot plasma called coronal mass ejections that hurtle through space at millions of miles per hour.

The sun’s wrath: The worst solar storms in history

When coronal mass ejections hit Earth, they can fry satellites in orbit and trigger major disturbances known as geomagnetic storms that can wreak havoc on electrical grids. For example, in 1989, a coronal mass ejection blacked out the entire Canadian province of Quebec within seconds, damaging transformers as far away as New Jersey and nearly shutting down U.S. power grids from the mid-Atlantic through the Pacific Northwest.

“Coronal mass ejections can have a serious impact on Earth and human society,” study co-author Yuta Notsu, an astrophysicist at the University of Colorado Boulder, said in a statement.

Previous research found that distant yellow dwarf stars could erupt with “superflares,” outbursts packing 10 times more energy than the largest known solar flares. Superflares could theoretically blast out equally super coronal mass ejections much more powerful than any produced by our sun, but until now astronomers had not seen any evidence that was true.

“Coronal mass ejections are the most important aspect when it comes to considering the effects of superflares on planets, especially our Earth,” Notsu told Space.com.

In the new study, the researchers analyzed EK Draconis, a star located about 111 light-years from Earth. EK Draconis is a yellow dwarf like the sun, but is much younger at only 50 million to 125 million years old. “It’s what our sun looked like 4.5 billion years ago,” Notsu said in the statement.

Prior work found that EK Draconis often erupted with flares, which suggested that astronomers monitoring it could get lucky in the hunt for superflares and giant coronal mass ejections. In the new study, the scientists observed EK Draconis from January to April 2020 using NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, Kyoto University’s Seimei telescope and the Nishi-Harima Astronomical Observatory’s Nayuta telescope.

On April 5, 2020, the research team’s hunch paid off — the scientists detected a superflare that was followed about 30 minutes later by what appeared to be a coronal mass ejection moving at about 1.1 million mph (1.8 million kph). They estimated its mass to be 10 times bigger than that of the largest known solar coronal mass ejection.

“This is the first detection of a possible coronal mass ejection from a solar-type star,” Notsu told Space.com.

Related stories:

Notsu noted that the team was only able to catch the initial phase of the coronal mass ejection, so it remains uncertain whether it fell back onto the star or got ejected into space. Future research should employ a range of telescopes in order to investigate the later phases of coronal mass ejections around other stars, he said.

These findings suggest the young sun may have also blasted out giant coronal mass ejections that could in turn have influenced the early Earth. “In other words, coronal mass ejections may be strongly related with the environment where life was born,” Notsu told Space.com.

Notsu noted that superflares on our sun do appear rare. Still, data from tree rings and other sources suggest the sun may have hit Earth with superflares multiple times in the past 10,000 years, he added.

“Discussions over the possibilities and effects of superflares and super coronal mass ejections on our society are important,” Notsu said.

The scientists detailed their findings online Dec. 9 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Originally published on Space.com. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.