Strong winds and rain at the European spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana, were responsible for the latest delay of the James Webb Space Telescope launch. But there is also another type of weather that might interfere with the grand telescope’s journey to orbit: space weather. So what does the space weather forecast look like for the upcoming big day of international astronomy?

NASA experts are keeping a close eye on three aspects of space weather to greenlight James Webb Space Telescope‘s launch: the global index of geomagnetic activity (also known as the Kp index), the state of the Van Allen Belts (the two regions around Earth where high-energy particles get trapped by the planet’s magnetic field), and solar energetic particles that sometimes escape from the sun.

“Impacts of space weather come in many forms and can cause problems for what we’re doing,”Jim Spann, space weather lead at NASA Headquarters in Washington, said in a statement. “We’re going to have to pay a lot of attention to space weather.”

Related: How the James Webb Space Telescope works in pictures

How can each of the three aspects of space weather affect the James Webb Space Telescope? And what does the space weather forecast hold for tomorrow?

The Kp index, carefully observed by those wishing to glimpse the northern lights, is a measure of the disturbance to Earth’s magnetic field caused by the solar wind, the stream of charged particles emanating from the sun. Its value ranges from 0 to 9. A rating above 4 is considered a geomagnetic storm. If that was on the cards, the James Webb Space Telescope would probably have to stay put as the magnetic disturbances could affect the spacecraft’s ability to communicate with Earth.

So far it seems that the Kp index won’t halt the (already heavily delayed) launch. The current forecast for tomorrow, Dec. 25, expects values between 1 and 3, according to SpaceWeatherLive.com.

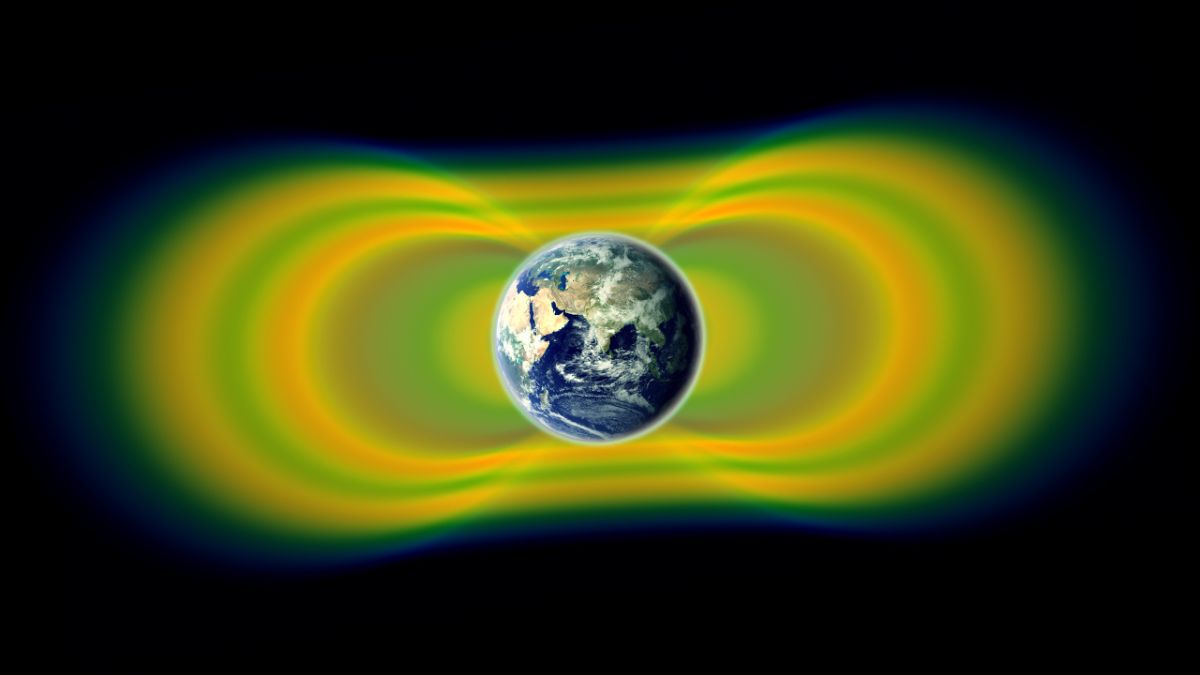

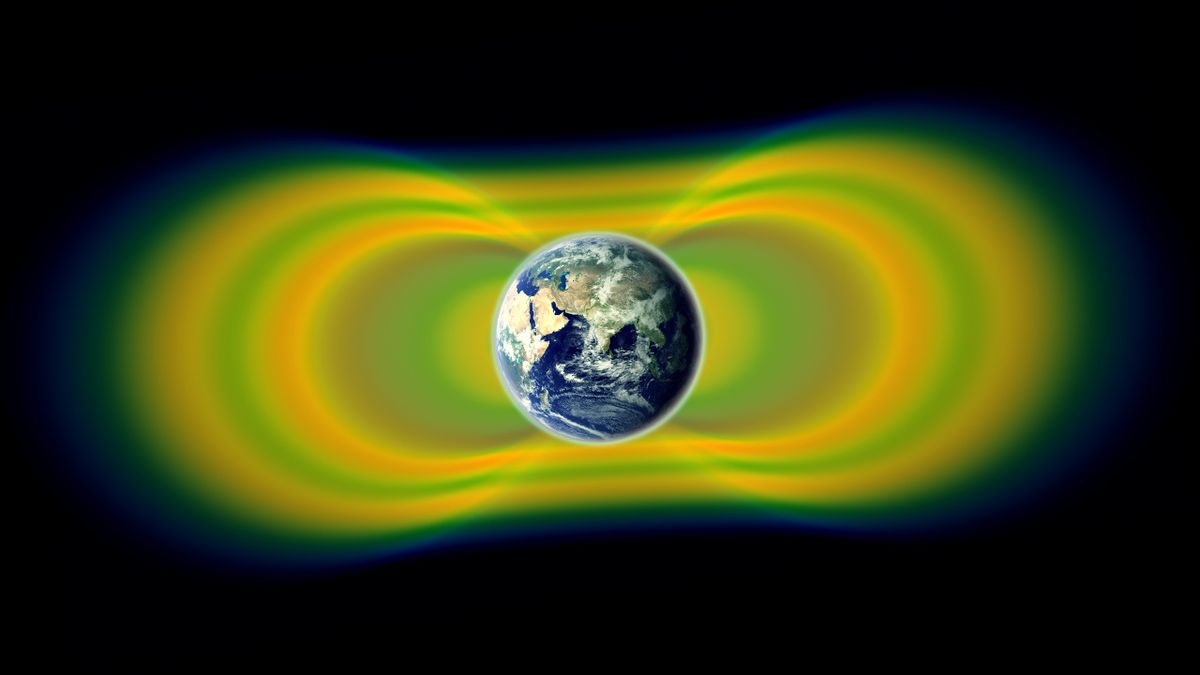

The James Webb Space Telescope launch teams also carefully monitor the amount of electrons trapped in the Van Allen Belts. These two doughnut-shaped regions extend above Earth at altitudes of 400 to 6,000 miles (650 to 9,660 kilometers) and 8,400 to 36,000 miles (13,500 to 60,000 km) respectively.

Earth’s magnetic field traps particles from the sun in the Van Allen Belts. When a solar storm hits the planet, the belts get re-energized, which could possibly cause problems to a passing spacecraft by building up electric charge on its surface.

“You know when you take something out of the dryer, and if you touch somebody you get that zap?” Spann said. “That’s what can happen when you charge the surface of a spacecraft.”

During these zaps, excess currents run through the spacecraft’s circuits, which could possibly cause a short circuit or affect the performance of solar panels.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite-17 (GOES-17) measures electron content in the outer Van Allen Belt so the James Webb Space Telescope teams will understand the risks very well.

Related content:

The final problem are the so called solar energetic particles (SEPs), extremely fast electrons and photons ejected from the sun at speeds of thousands of miles per second. Scientists still can’t reliably predict their presence in space around Earth, but they seem to be more common when there are active regions on the sun, the spots from which solar flares can erupt.

If a spacecraft gets hit by an SEP, its computer can get all confused, mixing up 0s for 1s in its binary code. According to NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center, there are currently no risks forecasted for the Christmas Day launch of the James Webb Space Telescope.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.