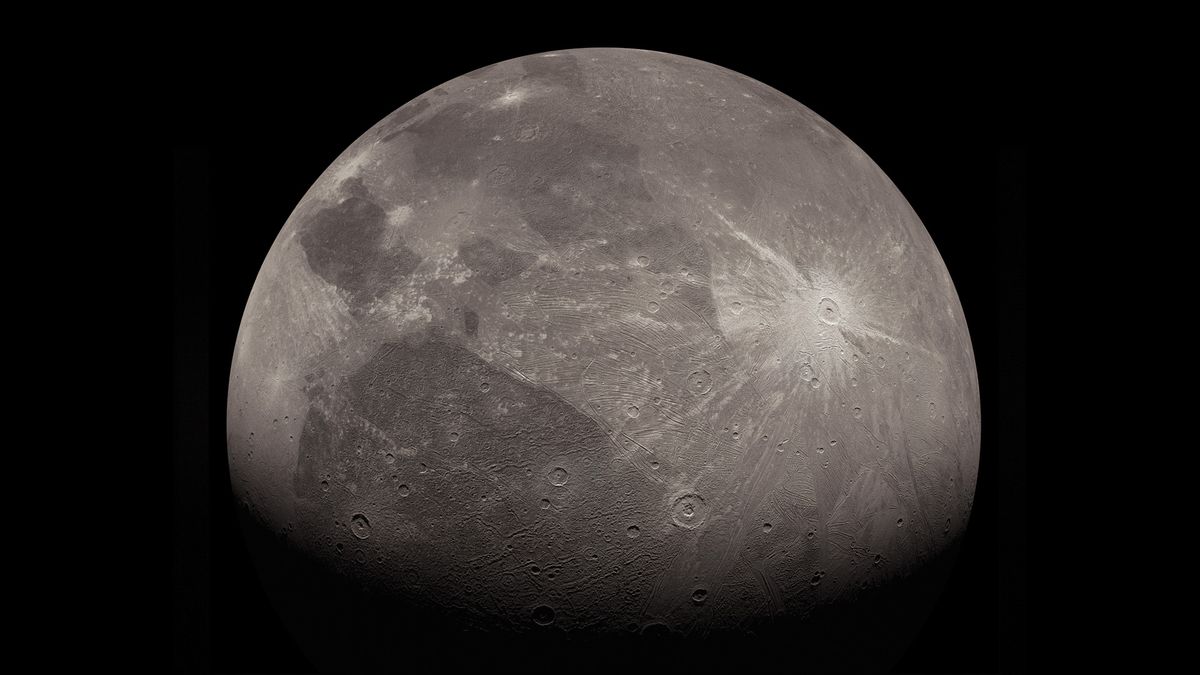

After a NASA mission passed within 620 miles (1,000 kilometers) of Jupiter’s largest moon Ganymede in June 2021, scientists are still decoding what the encounter can teach us about the strange world.

Two missions have previously imaged Ganymede, the largest moon in the solar system, Voyager 1 mission in 1979 and the Galileo spacecraft in the mid 1990s. Some of those images, however, were taken at a less than ideal angle, leaving large blank spots that scientists knew nothing about; technology has also improved dramatically since those missions launched. So scientists were thrilled when NASA’s Jupiter explorer Juno revealed the moon’s crater-covered surface in the greatest detail ever and spotted shimmering auroras stretching between Ganymede’s poles and equator.

These images outlined a plethora of new features on Ganymede’s surface, including impact craters as large as 60 miles (100 kilometer) wide, Goeffrey Collins, a geologist at Wheaton College in Massachusetts, said at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference that took place March 7 to 11 in Texas.

Related: Hear Jupiter’s moon Ganymede, the largest in the solar system, sing in new squeaky Juno video

“We missed some really big impact craters that we just couldn’t see in the Voyager data,” Collins said. “This should be a cautionary tale for trying to map things off just one image with one lighting angle, one viewing angle. We missed this big 100 kilometer crater that’s really obvious in the JunoCam data. And another, a little less obvious crater that is about 110 kilometers [68 miles] wide.”

The images also revealed several smaller craters, 25 to 30 miles (40 to 50 km) wide, and multiple features that the scientists believe might be a result of Ganymede’s volcanic activity.

“We have found caldera-like features, similar to those that we have seen previously in other parts of Ganymede,” said Collins. Calderas are volcanic craters that in the case of Ganymede were likely created by cryovolcanoes that spout frozen water and gas from the moon’s interior.

The number of these features seen in the Juno images suggests a much more intense volcanic activity on the moon than scientists expected previously.

“This actually bumps up the number of total caldera-like features that we found on all of Ganymede by 30%,” said Collins. “It definitely makes us think that we have undercounted these so far. There might be a lot more of these to be found on Ganymede as we get new data.”

Not only is Ganymede the largest moon in the entire solar system, 26% larger than the planet Mercury, it is also the only moon that we know has its own magnetic field. The variations in this magnetic field led scientists to conclude that the moon must have a massive underground ocean of salty water, which is up to 60 miles deep and hidden underneath a 95-mile-thick (150 km) crust of ice and rock. The ocean makes Ganymede a prime candidate for the existence of primitive forms of life.

Orbiting 665,000 miles (1.07 million km) away from the gas giant Jupiter, Ganymede is embedded within Jupiter’s magnetic field and enormous gravity, which attracts passing asteroids and comets.

The interplay between the magnetic fields of Ganymede and Jupiter gives rise to bright auroras on the former, the only such displays ever observed on a moon. Ganymede’s auroras were discovered in images from the Hubble Space Telescope, but the recent Juno flyby enabled scientists to gain more insights into these shimmering spectacles.

Related stories:

“We were now able to see the exact locations of the [auroral] emissions,” Pippa Molyneaux, a researcher at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas, said at the conference. “We were able to see the latitudinal extent of the aurora for the first time and we see that there are very sharp boundaries at the poleward edges of both [aurora] ovals, whereas when you move towards the equator, the emissions fall off more gradually, so future models would have to explain this.”

Ganymede will be the main target of the upcoming European Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE), which is expected to launch next year.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.