This article was originally published at The Conversation. (opens in new tab) The publication contributed the article to Space.com’s Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Cassandra Steer (opens in new tab), Deputy Director, Institute for Space (InSpace), Australian National University

NASA plans to launch the Artemis 1 lunar mission this Saturday (Sept. 3) after a first attempt earlier in the week was canceled at the last minute due to engine trouble.

The mission is an exciting step towards returning humans to the moon for the first time since 1972. But this time it’s not just about putting our footprints on lunar dust: it marks the beginning of a new space race for lunar resources. This time around, everybody wants to mine the moon.

Related: NASA’s Artemis 1 moon mission explained in photos

Return to the moon

Much about the Artemis program is noble and inspiring.

Artemis 1 is the program’s first mission, and it will carry out a 42-day uncrewed test flight to orbit the moon and return to Earth. The trip will use a new launch vehicle, the Space Launch System (SLS), which is the most powerful rocket currently operational in the world.

On board will be three mannequins made of materials replicating male and female biology (opens in new tab). NASA will use the mannequins to test the comfort and safety of the launch vehicle and spaceflight capsule for humans.

There are also many other experiments on board, and a series of small satellites will be launched to provide data when the capsule nears the moon.

The lessons from this mission will be applied to Artemis 2, the mission planned for 2024 (opens in new tab) that will see the first woman and the first person of color reach the moon.

A new space race?

However, humanity’s return to the moon is not all about exploration and the pursuit of knowledge. Just as the 1960s space race was driven by Cold War geopolitics, today’s space programs are underpinned by today’s geopolitics.

Artemis is led by the US, with participation by the European Space Agency (opens in new tab) and many other friendly nations including Australia.

China and Russia are collaborating on their own moon program (opens in new tab). They plan to land humans in 2026 and construct a moon base by 2035.

India too is working on robotic moon landers and a lunar spaceflight program. The UAE plans to launch a lunar lander in November this year (opens in new tab) as well.

All of these programs are aiming to do more than simply land astronauts for brief visits to the moon. The longer-term goal of the race is to acquire lunar resources.

Resources on the moon

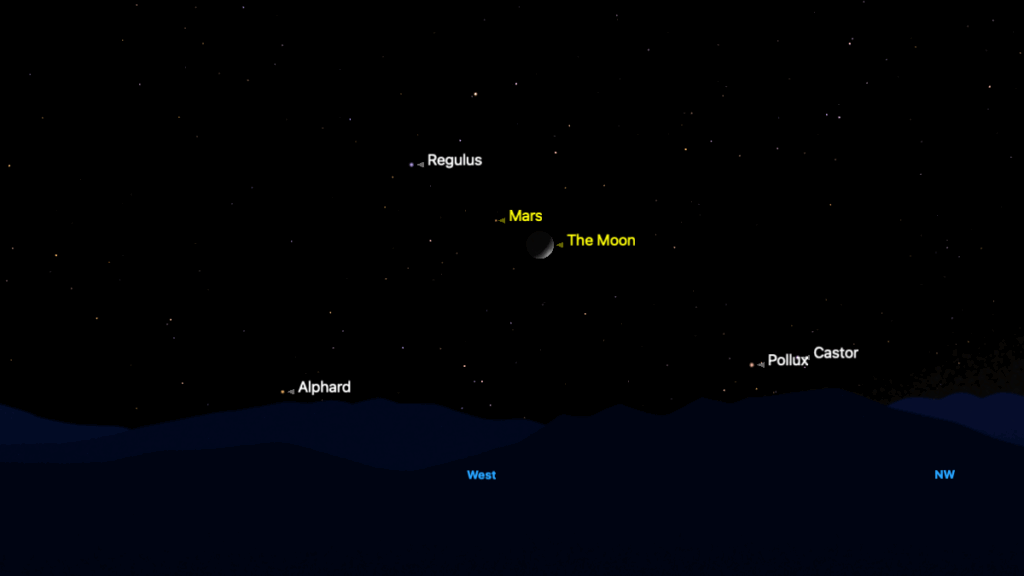

Water ice (opens in new tab) has been found in the southern regions of the moon, and it is hoped certain gases that can be used for fuels can also be mined.

These resources could be used to support long-term human habitation on and near the moon in lunar bases, as well as permanent space stations orbiting the moon, such as NASA’s planned Gateway.

The Australian Space Agency is supporting Australian industry (opens in new tab) to be part of the Artemis program and America’s planned later voyages to Mars. Australian scientists are also developing lunar rovers (opens in new tab) to assist lunar mining efforts.

Eventually, what we learn on the moon will be used to advance to Mars. But, in the near term, the countries and associated commercial entities that get to the best mining sites first will dominate an emerging lunar economy and lunar politics.

What are the rules?

In the next five years or so we can expect to see enormous political tensions rising around this new race to the moon.

One question that is yet to be answered: what laws will govern activities on the moon?

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty prohibits appropriation in space “by claims of sovereignty, occupation or by any other means (opens in new tab).” It is so far unclear whether mining or other forms of resource extraction fall under this prohibition.

The United Nations has a working group (opens in new tab) that aims to develop a multilateral consensus on legal aspects of space resource activities.

However, in 2020 the US got out in front of the UN process by establishing the Artemis Accords (opens in new tab), which state that resource extraction will occur and is lawful. Twenty-one countries (opens in new tab), including Australia, have signed these accords with the US, but they are far from universally accepted.

Another relevant treaty is the 1979 Moon Agreement, signed by 18 countries including Australia. This agreement states that no entity can own any part of the moon, and obliges us to establish a regulatory regime for lunar mining “at such a time as the technology is about to become feasible (opens in new tab).”

Australia is therefore between a lunar rock and a hard place as to what role we will play in developing these new laws. But international law-making and consensus-building are slow: most likely actual practice will be established in the next few years, and decisions on how to govern it will come after the fact.

Technical and political challenges

There is some poetic perfection in NASA having chosen the name “Artemis” for this new lunar endeavor. Artemis is the Greek goddess of the moon, and the twin sister of Apollo (the namesake of NASA’s 1960s moon spaceflight program).

Artemis declared she never wanted to be married (opens in new tab) because she didn’t want to become the property of any man.

Even if ownership of the moon cannot be claimed, we will see competition over whether parts of it can be mined. No doubt scientists and engineers will resolve the technical challenges of the return to the moon. Resolving the legal and political challenges may prove more difficult.

This article is republished from The Conversation (opens in new tab) under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article (opens in new tab).

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook and Twitter. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.