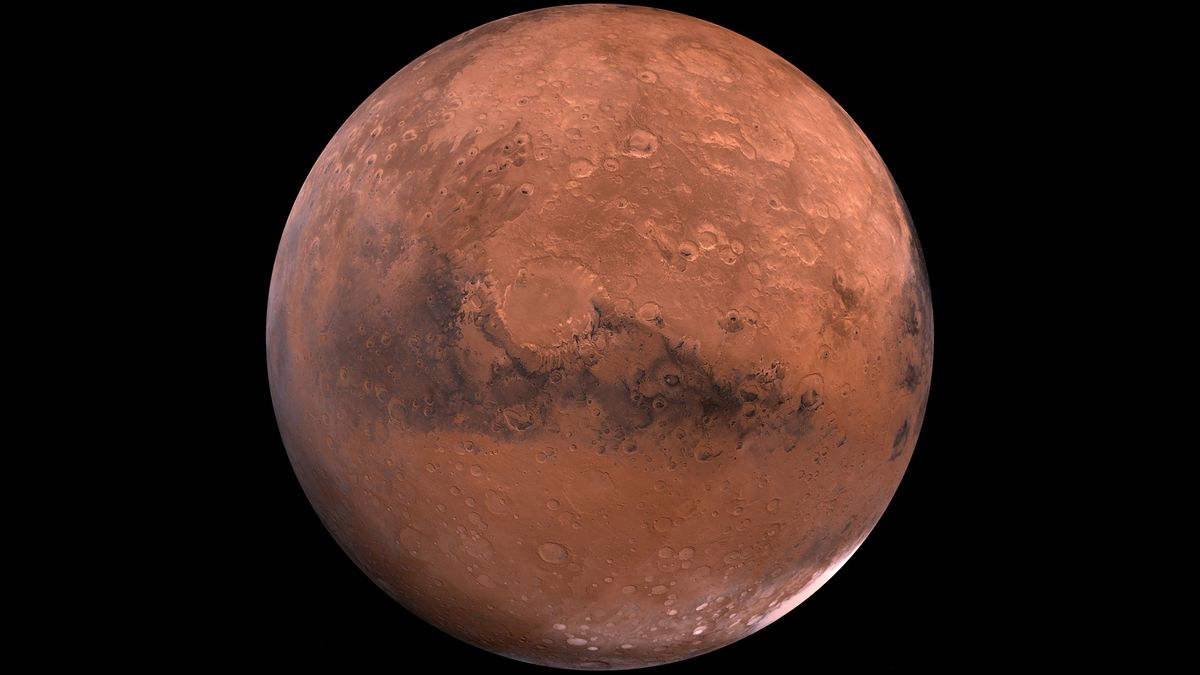

As regularly happens in science, new information has challenged a long-held theory — this time as it relates to the crust on Mars.

Previously, scientists thought the origin of the Martian crust was relatively straightforward. Because the crust is uniformly basaltic (basalt is an igneous rock), it was theorized that its formation occurred when a planet-wide ocean of magma cooled. But new research indicates that certain areas of the Martian crust have a higher silica content than expected, and that changes the story.

“There is more silica in the composition that makes the rocks not basalt, but what we call more evolved in composition,” Valerie Payré, an assistant professor at the University of Iowa who led the study, said in a statement. “That tells us how the crust formed on Mars is definitely more complex than what we knew.”

Related: What is Mars made of?

Payré and her team used data from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter to study the composition of the Martian crust in the southern hemisphere, where they discovered the mineral feldspar. Feldspar is associated with silica-rich lava flows rather than basaltic ones.

This discovery promotes a different theory of Martian crust evolution — one that suggests that the crust formed in multiple phases, which would be a more complex process than the cooling of a huge magma ocean.

“There have been rovers on the surface that have observed rocks that were more silicic than basaltic,” said Payré. “So, there were ideas that the crust could be more silicic. But we never knew, and we still don’t know, how the early crust was formed, or how old it is, so it’s kind of a mystery still.”

Related stories:

More research is needed to help unravel those mysteries, which, in turn, could help scientists determine more about crust formation on Earth, too. Because of tectonic activity, our planet’s crust has a far more complicated history than Martian crust — or so we think right now.

“We don’t know our planet’s crust from the beginning; we don’t even know when life first appeared,” said Payré. “Many think the two could be related. So, understanding what the crust was like a long time ago could help us understand the whole evolution of our planet.”

The new study (opens in new tab) was published online last month in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Follow Stefanie Waldek on Twitter @StefanieWaldek (opens in new tab). Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or Facebook (opens in new tab).