The Red Planet’s harsh dust has claimed another spacecraft.

NASA announced Wednesday (Dec. 21) that its InSight lander, designed to understand the geologic life story of Mars, has completed its mission on the Red Planet. The spacecraft relied on solar power, and after four years on Mars, its sunlight-collecting panels have built up too much dust to generate enough power to run the lander. For months now, the InSight team have been expecting the lander to fall silent. Now, the robot has missed two calls home; scientists last heard from the robot on Dec. 15. NASA will keep listening, but doesn’t expect to hear anything more from the lander.

“We’ve actually been able to do a whole lot more than what we claimed and promised to do,” Bruce Banerdt, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California and principal investigator of the InSight mission, told Space.com earlier this year. “I feel like, looking back, this has been an enormously successful mission.”

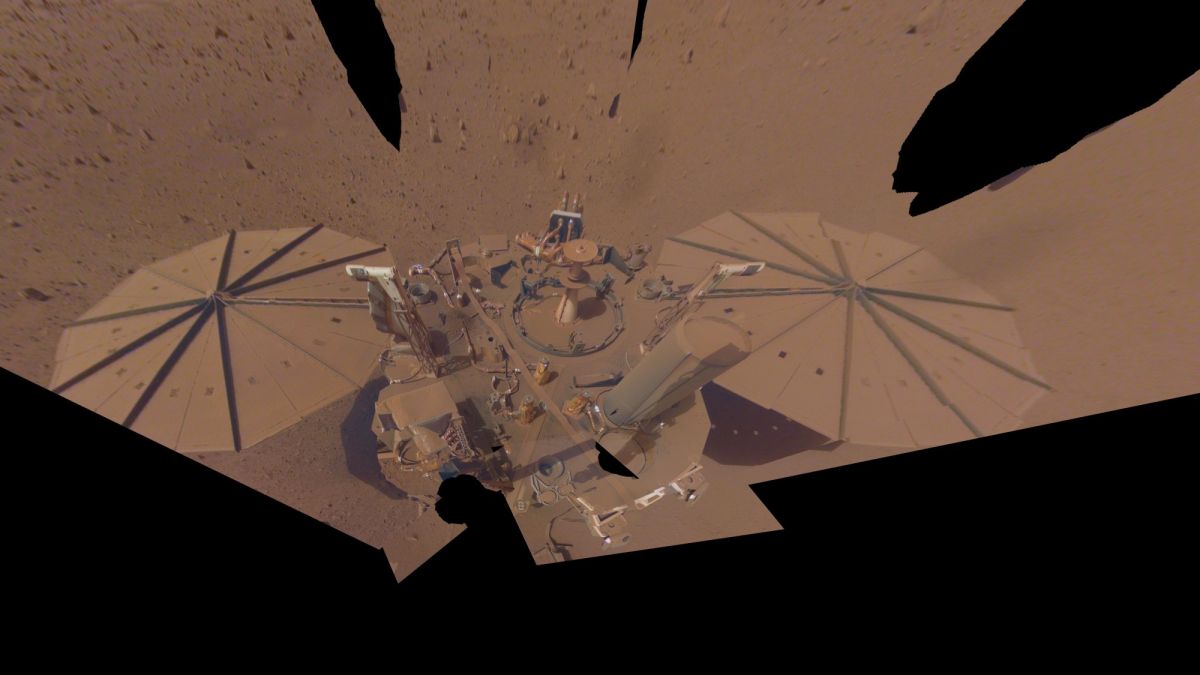

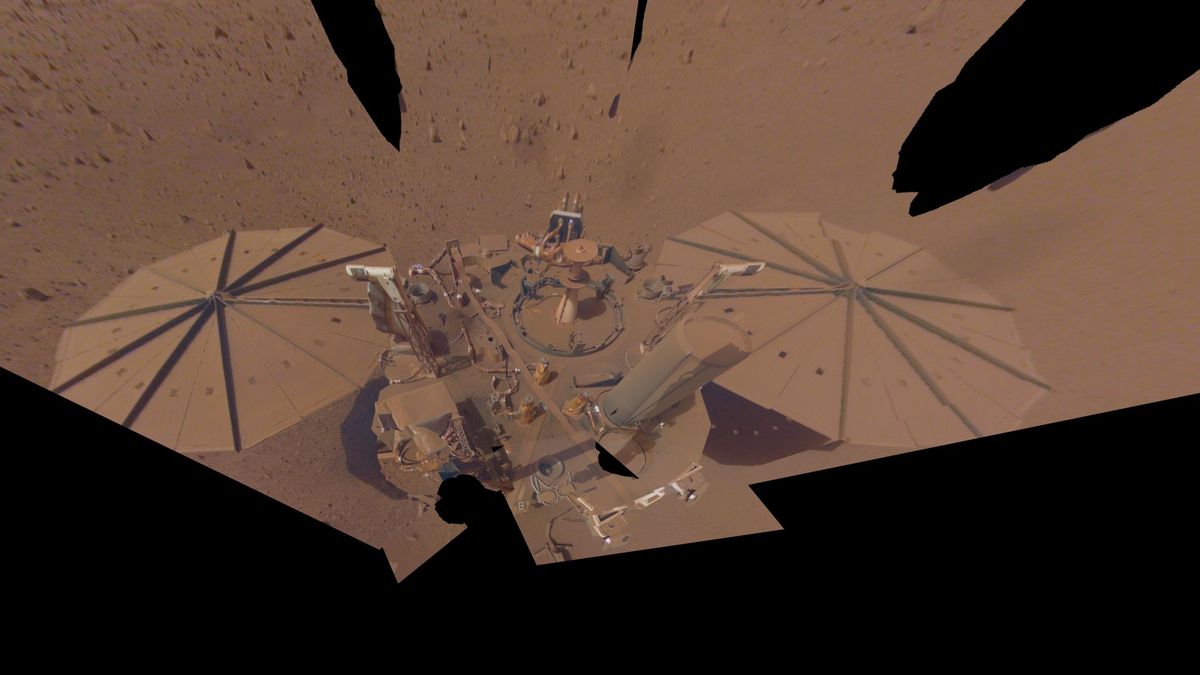

Related: NASA’s Mars InSight lander snaps dusty ‘final selfie’ as power dwindles

InSight launched in May 2018 and landed six months later; for four years, the $814 million robot quietly listened to the Red Planet’s rumblings.

Unlike its rover siblings Curiosity and Perseverance, which focus on evaluating the Red Planet’s habitability over time, InSight was designed to peer deep inside the planet, measuring the layers from the surface down to the molten core. The mission was also meant to track current geologic activity by feeling for marsquakes.

And InSight found success on both fronts, even when things didn’t go precisely according to plan.

“Mars itself has been surprising: It’s been more difficult in some ways and it’s been more forthcoming in some ways,” Banerdt said. “The places that were difficult, we were still able to eke out the information that we were looking for by getting more clever about the analysis and so forth. And the places where Mars was generous to us, we had things fall in our lap that we weren’t expecting.”

Unable to dig

Mars was particularly challenging when it came to the InSight instrument nicknamed “the mole,” officially known as the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package. The device was meant to hammer itself down 16 feet (5 meters) and measure how much heat is rising up from the deep core of Mars. But no matter what scientists tried, the mole couldn’t get a grip on the soil at InSight’s landing site, leaving it stuck near the surface.

The difficulty suggests that the ground below InSight is different than at locations NASA’s rovers have previously explored, according to Sue Smrekar, a planetary scientist at JPL and deputy principal investigator for InSight.

“Based on our understanding of what we saw elsewhere, yes, it should have worked,” Smrekar told Space.com earlier this year. She said she believes that the mole would have worked in one of those locations and that an adapted version could work even where InSight landed.

Even without digging properly, the mole still gathered limited data — but nothing like what scientists had hoped for. “It’s not the heat flow that we were really after, the big prize, and that’s been, for me personally, super frustrating,” Smrekar said.

The InSight team abandoned efforts to get the mole digging properly in January 2021, after troubleshooting the issue for nearly two years. “We knew from the beginning that this was a little bit of a tricky experiment,” Banerdt said.

Shaking up science

But where the mole’s patch of the Red Planet stymied InSight, another region of Mars was surprisingly generous: Cerberus Fossae. The region, which is scarred by faults and lies about 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) away from InSight,, has produced far more of the marsquakes the lander has detected than any other region.

“As far as we understand, there’s this one super-active area, and it defies the prediction of how cold Mars is, how inactive Mars is,” Smrekar said. “It allows us to see Mars as not a uniform and old and dead planet.”

InSight also gave scientists a better view inside Mars than any previous mission has managed, to great effect. “A lot of things are different than we imagined,” Smrekar said. “Based on the data that we had available, we had to make a lot of assumptions about the interior. Now we have this hard data, which gives us a much clearer picture of what’s going on inside the planet.”

InSight’s data has told scientists that the Martian crust, at least at the robot’s near-equatorial landing site, consists of two different layers: a top layer about 6 miles (10 km) thick that has been battered by impacts atop a deeper layer about 25 miles (40 km) thick. “We really didn’t have a clear picture about these multiple layers in the crust,” Smrekar said. Even now, she and her colleagues aren’t sure whether the two-layer structure occurs globally or only in particular regions.

In addition, InSight found that the core of Mars is much larger than scientists had expected; the finding also means that the core must contain greater amounts of lighter elements than scientists thought — in particular, more sulfur, perhaps as much as 15% to 20%, Banerdt said.

“That’s kind of broken our models of the core,” Banerdt said. “When you do an experiment and get data that breaks the models, that’s a real advance.”

(No one is sad to see the models go. “Planets are much more interesting than our models,” Smrekar said; after all, finding the strengths and weaknesses of current models is the point of any space mission.)

End of the line

The InSight team has spent recent months eking as much data out of the lander as possible. As the robot’s power production fell, mission personnel arranged for the seismometer to run in eight-hour chunks, buffered by time for the lander to recharge its battery.

“Every different kind of marsquake, every additional quake, it just adds another piece of the story of what’s going on inside Mars,” Smrekar said, noting that the lander caught its largest marsquake in early May, just two weeks before NASA announced that the mission was nearing its end. “It would be just fantastic if we could keep on.”

Related stories:

But no mission lasts forever — especially not a solar-powered Mars mission. The Red Planet’s dust is brutal for these spacecraft, piling up on solar panels and dramatically reducing the arrays’ power production. And the dust is a double whammy, since it also seasonally fills the skies, reducing the amount of sunlight that reaches the Martian surface.

The combination similarly did in NASA’s Opportunity rover in 2018, and now dust has ended InSight’s mission as well.

“It’s been an amazing spacecraft. It’s done everything that we’ve asked it to do and more,” Banerdt said. “It’s earned its retirement — I like to think of it as retiring and not dying. And it’s going to sit on Mars and enjoy the Martian sunsets for a while after it stops talking to us.”

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.