New X-ray observations of the sun could help crack the mystery of the star’s inexplicably hot outer atmosphere, the corona.

The sun is an unmistakable and unmissable feature in the sky over Earth, bathing our planet with light. Yet, not all of this light is visible to our eyes, which see only a relatively narrow band of the electromagnetic spectrum. New observations by NASA’s Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR) have revealed high-energy light from our star that our eyes are incapable of spotting.

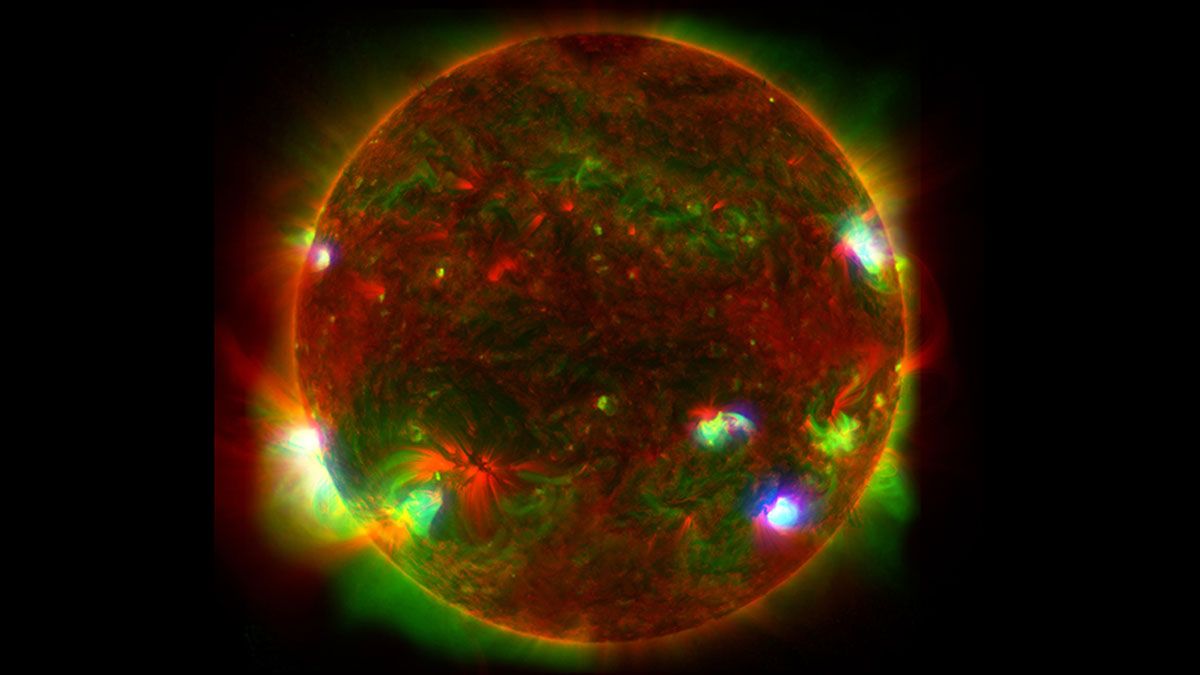

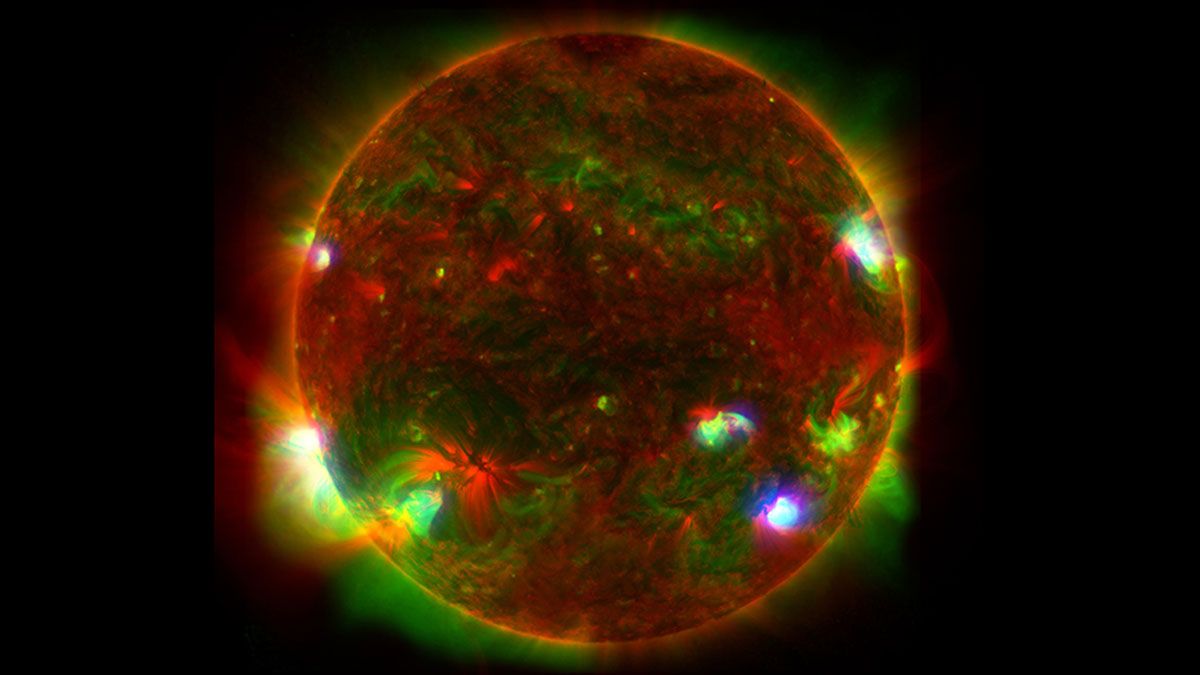

In an image, released by NASA (opens in new tab) on Friday, Feb. 10, patches of high-energy X-ray radiation captured by the NuStar telescope can be seen as bright blue spots. NuStar’s data is combined with observations of low-energy X-rays, made by Japan’s Hinode spacecraft , displayed in shades of green, and ultraviolet views taken by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), which appear in red colors.

Related: The sun as you’ve never seen it: European probe snaps closest-ever photo of our star

Solving the sun’s coronal heating mystery

NuStar’s observations are particularly valuable, as they reveal the hottest areas on the sun’s surface. Scientists think that these super hot regions, scattered randomly across the sun’s surface, could help find the solution to one of the oldest and most pressing solar mysteries: why the sun’s upper atmosphere, the corona, is so much hotter than its surface.

Common theories of star composition suggest that deeper layers should be hotter, and this is true everywhere throughout the sun except when passing from the upper atmosphere, the corona, which can reach temperatures of up to 3.6 million degrees Fahrenheit ( 2 million degrees Celsius), to the photosphere below, which, at about 6,200 degrees F (3,700 degrees C) is up to 500 times colder.

NASA says (opens in new tab) that because heat from the sun passes out from its core, this is as surprising as the air around a fire being 100 times hotter than the flames of the fire itself.

The source of this unexpected heating may be nanoflares, small bursts of heat, and light in the sun’s atmosphere. These are smaller than regular solar flares but like their larger cousins, also produce material hotter than the average temperature of the corona.

Regular flares don’t happen frequently enough to heat the corona, but nanoflares may happen more regularly, perhaps often enough to cause this excess heating.

Individual nanoflares are too faint to spot amongst the sun’s light output, but NuSTAR can spot radiation from high-temperature material created by a lot of nanoflares happening in the same location at the same time. This could eventually allow solar physicists to see the frequency of nanoflares, how they release energy, and thus whether they are responsible for coronal heating.

The data for this new mosaic image was collected as NASA’s sun-touching spacecraft, the Parker Solar Probe, made its 12th close pass of the star, racing through the outer limits of its corona and coming closer to the sun than any other craft ever had done before.

Related stories:

By linking NuSTAR’s observations of the sun with data gathered during the up close and personal visits of the Parker Solar Probe, researchers can connect visible activity on the sun with samples of the solar atmosphere collected by the spacecraft.

The observation of these tiny areas of extreme heating demonstrates that while NuSTAR was primarily designed to spot distant objects and events outside the solar system such as collapsed stars and black holes, it could also reveal lots of information regarding the sun. Because this telescope can only see part of the sun from its orbit around Earth, the image consists of 25 images taken in June 2022 stitched together.

Follow us on Twitter@Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or onFacebook (opens in new tab).