Dark energy, the mysterious force apparently driving the accelerating expansion of the universe, is spread evenly through space and time, new results suggest.

The findings also better constrain how much of the universe’s energy and matter content dark energy accounts for, the study team said.

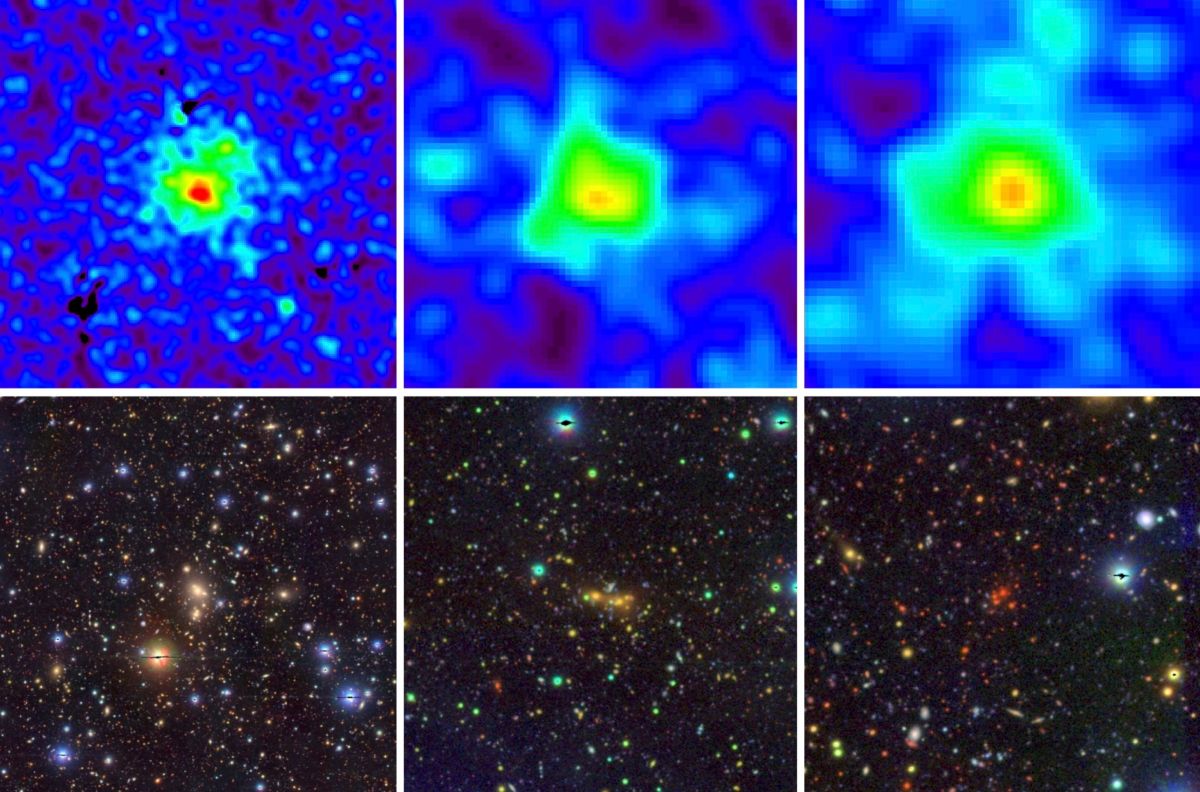

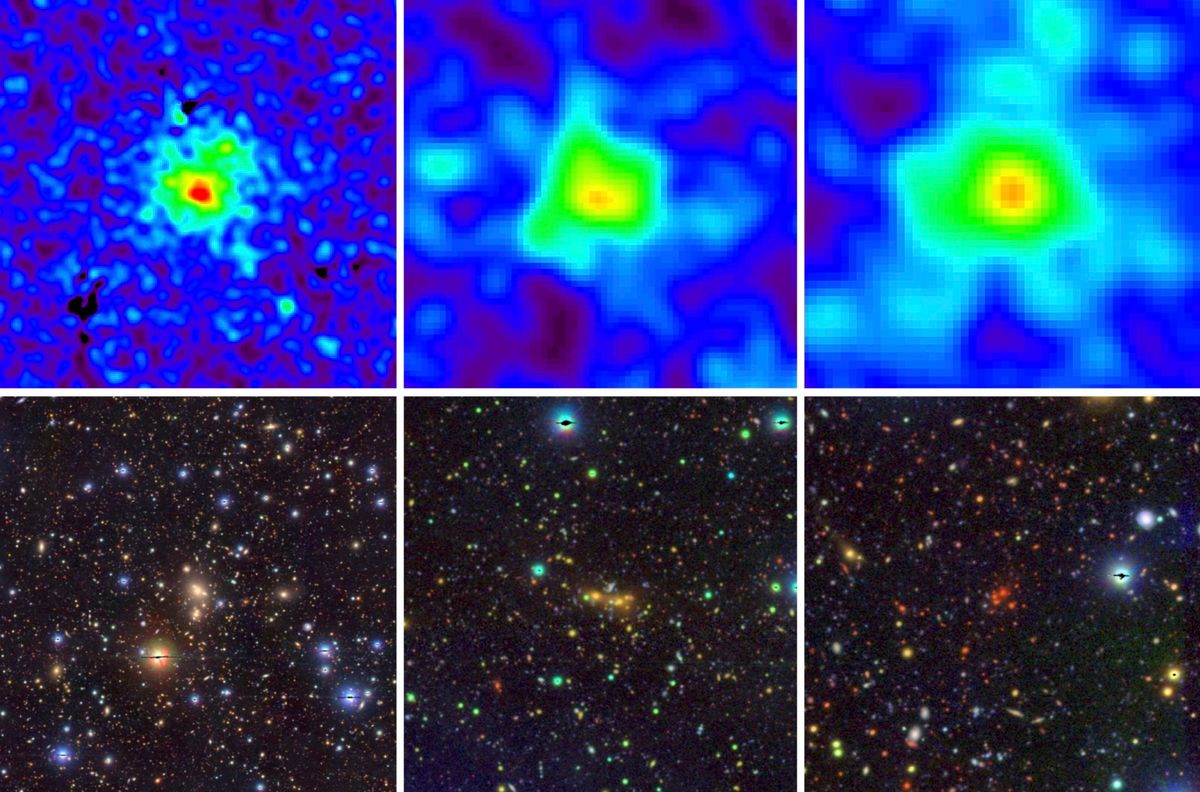

They reached their conclusions after analyzing observations of galaxy clusters made by the eROSITA X-ray instrument, which searches the entire sky over Earth for these find-to-find collections of galaxies. eROSITA is mounted on Spektr-RG, a Russian-German space telescope that launched to Earth orbit in 2019.

Related: Dark matter and dark energy: The mystery explained (infographic)

Galaxy clusters are useful for understanding dark energy because, on large scales, this odd repellant “anti-gravity” force should suppress the formation of enormous cosmic structures. That means dark energy determines how and where galaxy clusters, the largest objects in the universe, can form.

“We can learn a great deal about the nature of dark energy by counting the number of galaxy clusters formed in the universe as a function of time,” study co-author Matthias Klein, an astrophysicist at Ludwig-Maximillians-Universitat Munchen in Germany (LMU), said in a statement (opens in new tab).

The eROSITA Final Equatorial-Depth Survey (eFEDS) found about 500 galaxy clusters, one of the largest samples of low-mass galaxy clusters discovered to date. The observed clusters cover roughly the past 10 billion years of the 13.8 billion-year-old universe’s evolution.

The study team combined the eROSITA observations with optical data from the Hyper Suprime-Cam Subaru Strategic Program. This enabled the first cosmological study performed using galaxy clusters detected by eROSITA.

The results of the study were then compared to theoretical predictions, confirming that dark energy accounts for around 76% of the total energy density of the universe. The findings also suggest that this energy density is uniform in space and constant in time.

The team’s results agree well with other independent approaches to the investigation of dark energy, such as previous galaxy cluster studies as well as those using an effect of gravity on light called weak gravitational lensing. Yet, while the new findings shed more light on dark energy, this force remains a mystery that physicists are eager to get to the bottom of.

Why is dark energy so problematic?

In the 1920s, American astronomer Edwin Hubble made observations of distant galaxies that showed they are receding from us. In addition, the farther away a galaxy lies, the quicker it’s moving away, which led scientists to discover that the universe is expanding.

This was shocking enough, overturning the commonly held idea at the time that the universe existed in a stable steady state. Things got weirder in 1998, when observations of distant supernovas showed that, not only is the universe expanding, but this expansion is accelerating.

“To explain this acceleration, we need a source, and we refer to this source as ‘dark energy,’ which provides a sort of ‘anti-gravity’ to speed up cosmic expansion,” said study co-author Joe Mohr, an LMU astrophysicist.

Yet, despite knowing what dark energy does and being able to calculate that it comprises around 76% of the energy and matter in the universe, scientists still are in the dark about what it actually is, or why it started acting on the universe in its later epochs.

The effect of dark energy causing accelerating expansion in the later universe, after the initial rapid expansion of the universe as a result of the Big Bang ended, is something like applying an initial push to a child on a swing. As the child slows toward a halt, the swing starts to pick up speed again, without any further push. Not only that, but it accelerates faster and faster and reaches increasingly greater heights.

Just like the swing analogy, the accelerating expansion of the universe tells scientists that something is missing from their picture of the cosmos.

RELATED STORIES:

“Although the current errors on the dark energy constraints are still larger than we would wish, this research employs a sample from eFEDS that, after all, occupies an area less than 1% of the full sky,” added Mohr. “The nature of dark energy has become the next Nobel Prize-winning problem.”

The team’s research was published last month in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (opens in new tab).

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) and on Facebook (opens in new tab).