The new year of 1969 dawned with optimism that NASA would meet President John F. Kennedy’s goal of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth. The previous year saw four Apollo missions, two uncrewed and two carrying three astronauts each, test different components of the lunar landing architecture, culminating with Apollo 8’s December flight around the Moon. Challenges remaining for the new year included testing the Lunar Module (LM) with a crew, first in Earth orbit, and then in lunar orbit, a flight that served as a dress rehearsal for the Moon landing that could take place on the following mission. With flights occurring every two months, engineers at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida processed three spacecraft and launch vehicles in parallel.

Recovering from the fire

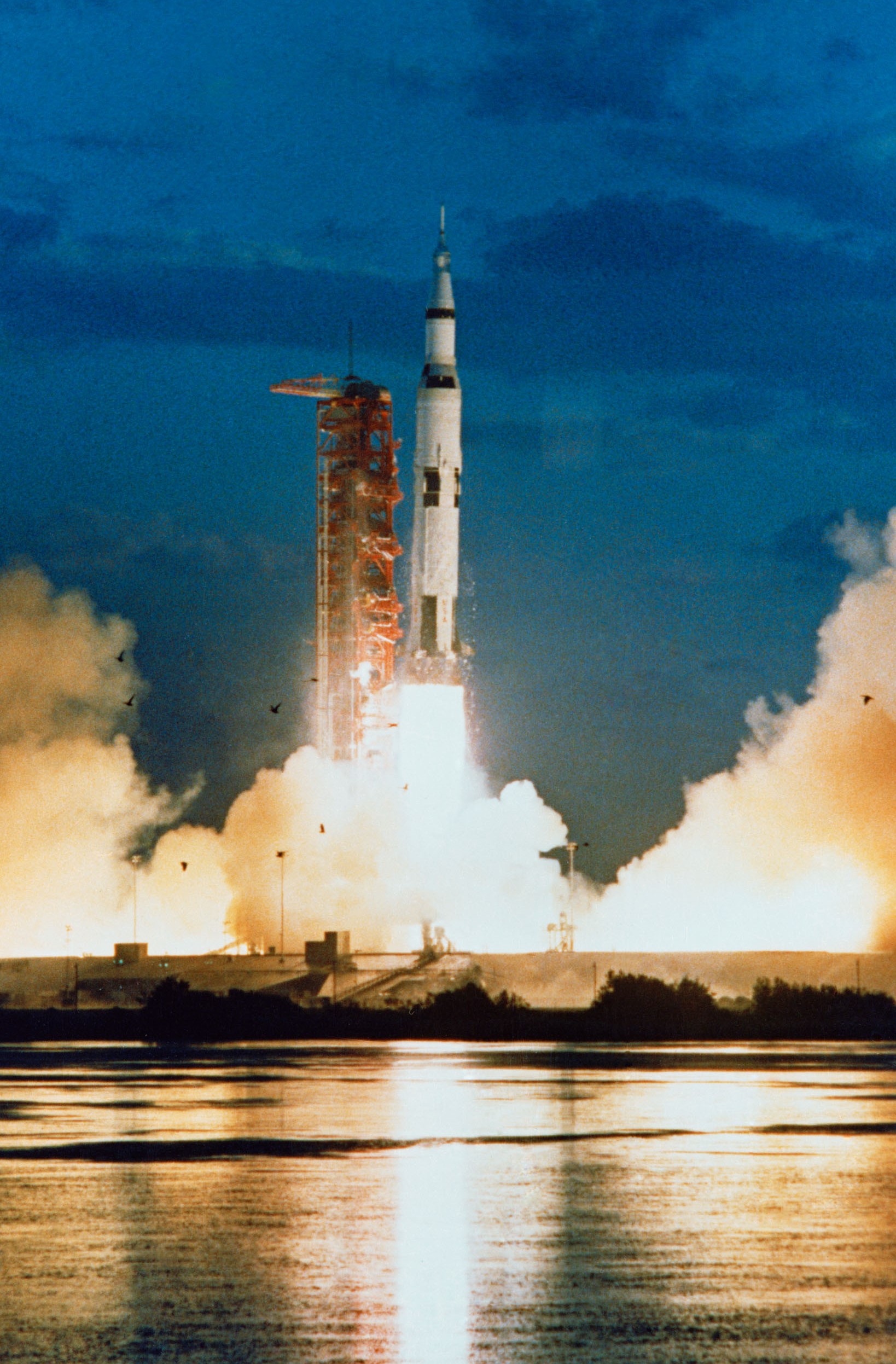

Left: The Apollo 1 crew of Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom, left, Edward H. White, and Roger B. Chaffee. Middle left: Liftoff of the first Saturn V on the Apollo 4 mission. Middle right: The Lunar Module for the Apollo 5 mission. Right: Recovery of the Apollo 6 Command Module.

The years 1967 and 1968 proved turbulent for the world. For NASA, the focus remained on recovering from the tragic Apollo 1 fire in time to meet President Kennedy’s fast approaching end of the decade deadline. The fire resulted in a thorough redesign of the Command Module (CM) to reduce flammability risks and to include an easy to open hatch. Engineers also removed flammable materials from the Lunar Module (LM). In November 1967, the first flight of the Saturn V carried Apollo 4 on a nine-hour uncrewed mission to test the CM’s heat shield. Apollo 5 in January 1968 completed an uncrewed test of the LM so successful that NASA decided to cancel a second test. Although fraught with problems, the April 1968 flight of Apollo 6 tested the CM heat shield once again. Managers believed that engineers could solve the problems encountered during this mission and declared that the next Saturn V would carry a crew.

Apollo 7 and 8

Left: Apollo 7 astronauts Walter M. Schirra, left, Donn F. Eisele, and R. Walter Cunningham on the recovery ship USS Essex following their 11-day mission. Right: The famous Earthrise photograph from Apollo 8.

By October 1968, thorough ground testing of the Apollo spacecraft enabled the first crewed mission since the fire. Apollo 7 astronauts Walter M. Schirra, Donn F. Eisele, and R. Walter Cunningham successfully completed the 11-day test flight, achieving all mission objectives. In August, with LM development running behind schedule, senior NASA managers began discussions of sending Apollo 8 on a circumlunar flight, pending the outcome of Apollo 7. With that hurdle successfully cleared, astronauts Frank Borman, James A. Lovell, and William A. Anders orbited the Moon 10 times during Christmas 1968, taking a giant leap toward achieving the Moon landing.

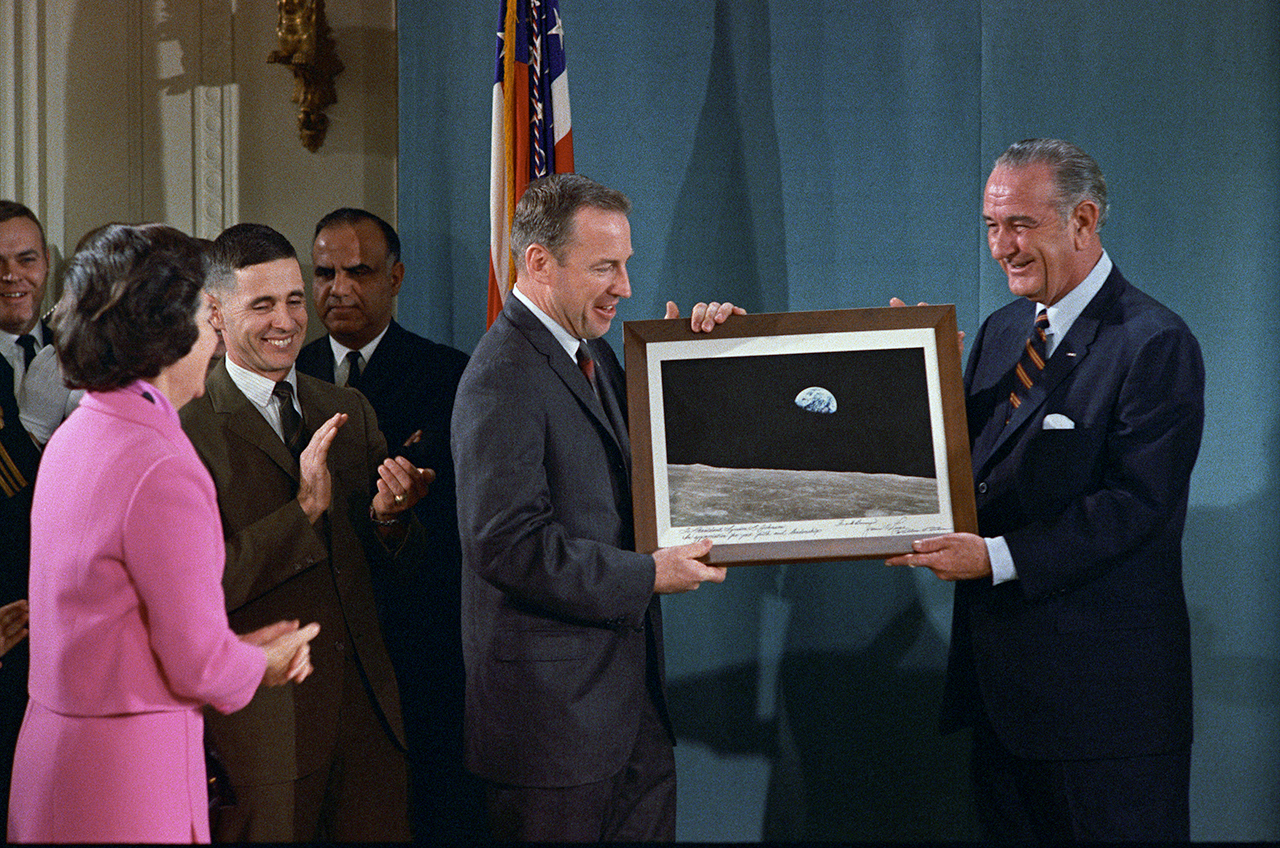

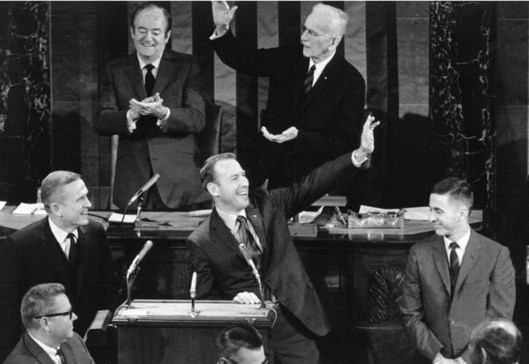

Left: At the White House, Apollo 8 astronauts Frank Borman, James A. Lovell, and William A. Anders present a copy of the Earthrise photograph to President Lyndon B. Johnson. Middle: Accompanied by Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey, Borman, Lovell, and Anders take a motorcade from the White House to the Capitol. Right: Borman, left, Lovell, and Anders address a joint meeting of Congress.

With their space missions completed, the Apollo 7 and 8 crews remained busy with events celebrating their successes. On Jan. 3, 1969, TIME magazine named Apollo 8 astronauts Borman, Lovell, and Anders their Men of the Year for 1968. Kicking off a whirlwind of events, on Jan. 9, outgoing President Lyndon B. Johnson welcomed them to the White House, where he presented them with NASA Distinguished Service Medals. They in turn presented him with a copy of the famous Earthrise photograph. Accompanied by Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey, Borman, Lovell, and Anders rode in a motorcade down Pennsylvania Avenue to the Capitol where the astronauts addressed a joint meeting of Congress. From there, they proceeded to the State Department for a press conference, their day ending with a dinner in their honor at the Smithsonian Institution.

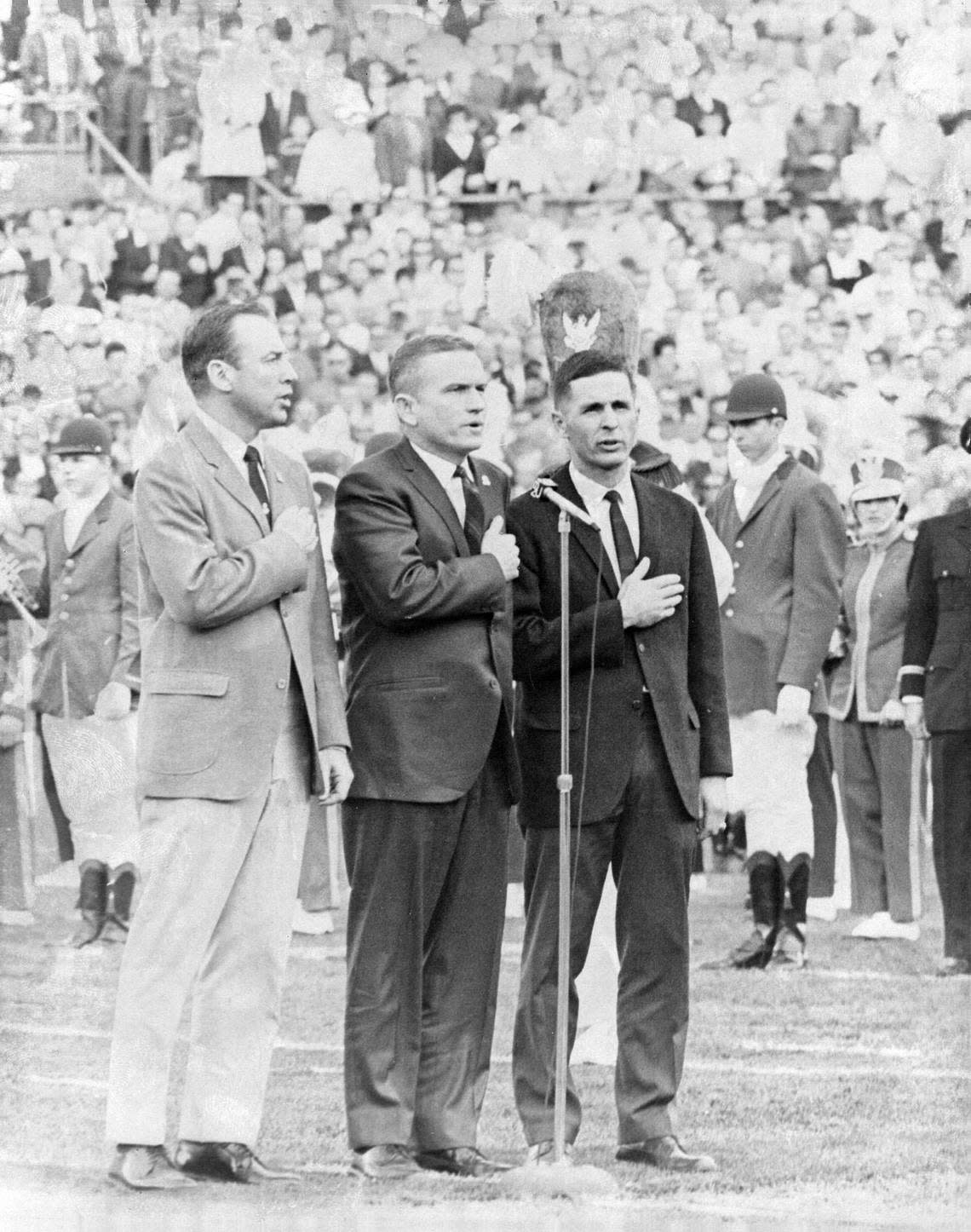

Left: Apollo 8 astronauts James A. Lovell, left, Frank Borman, and William A. Anders wave to the crowds assembled along their parade route in New York City. Middle: Borman, Lovell, and Anders address a crowd at Newark airport. Right: In Miami’s Orange Bowl Lovell, left, Borman, and Anders lead the fans in the Pledge of Allegiance at Super Bowl III.

On Jan. 10, New York City held a tickertape parade for Borman, Lovell, and Anders. Mayor John V. Lindsay presented them with Medals of the City of New York, after which they attended a luncheon at Lincoln Center, a reception at the United Nations, and dinner at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. The next day, in 15-degree weather, they spoke to a crowd of about 1,500 people at Newark Airport before boarding a plane for much warmer Miami, where on Jan. 12 they attended Super Bowl III, and led the Orange Bowl crowd in reciting the Pledge of Allegiance.

Left: In Houston, Apollo 8 astronauts William A. Anders, left, Frank Borman, and James A. Lovell present an Earthrise photograph and flags of Texas to Governor John B. Connally, far right, and Mayor Louie Welch, hidden behind the photograph. Middle: Borman and his family in the parade through downtown Houston, with Lovell and Anders and their families following behind. Right: Lovell, Borman, and Anders wave to the crowds in the parade in Chicago.

A crowd estimated at about 250,000 welcomed Borman, Lovell, and Anders home to Houston on Jan. 13. In a ceremony outside the Albert Thomas Convention Center, Mayor Louie Welch presented them with bronze medals for heroism, and the astronauts presented Welch and Texas Governor John B. Connally with plaques bearing Texas flags they had flown to the Moon as well as a framed copy of the Earthrise photograph. The astronauts took part in the largest parade in the city’s history. The next day, the city of Chicago welcomed Borman, Lovell, and Anders. An estimated 1.5 million people cheered them on their parade route to a reception where they received honors from city council.

Left: The Apollo 7 Command Module and a Lunar Module mockup on a float in President Richard M. Nixon’s inauguration parade; Apollo 7 astronauts Walter M. Schirra, R. Walter Cunningham, and Donn F. Eisele preceded the float in an open-air limousine. Image credit: courtesy Richard Nixon Library. Right: Apollo 8 astronauts Frank Borman, left, James A. Lovell, and William A. Anders with President Nixon at the White House.

On Jan. 20, Apollo 7 astronauts Schirra, Eisele, and Cunningham rode in President Richard M. Nixon’s inauguration parade in Washington, D.C. Their spacecraft and a LM mockup rode on a float behind them. Ten days later, the new President invited Apollo 8 astronauts Borman, Lovell, and Anders to the White House where he announced that Borman and his family would embark on an 18-day goodwill tour of eight European nations, starting on Feb. 2.

Apollo 9

The LM remained the one component of the lunar landing architecture not yet tested by astronauts in space. That task fell to James A. McDivitt, David R. Scott, and Russell L. Schweickart, the crew of Apollo 9. They and their backups Charles “Pete” Conrad, Richard F. Gordon, and Alan L. Bean spent many hours in the LM simulators and training for the spacewalk component of the mission.

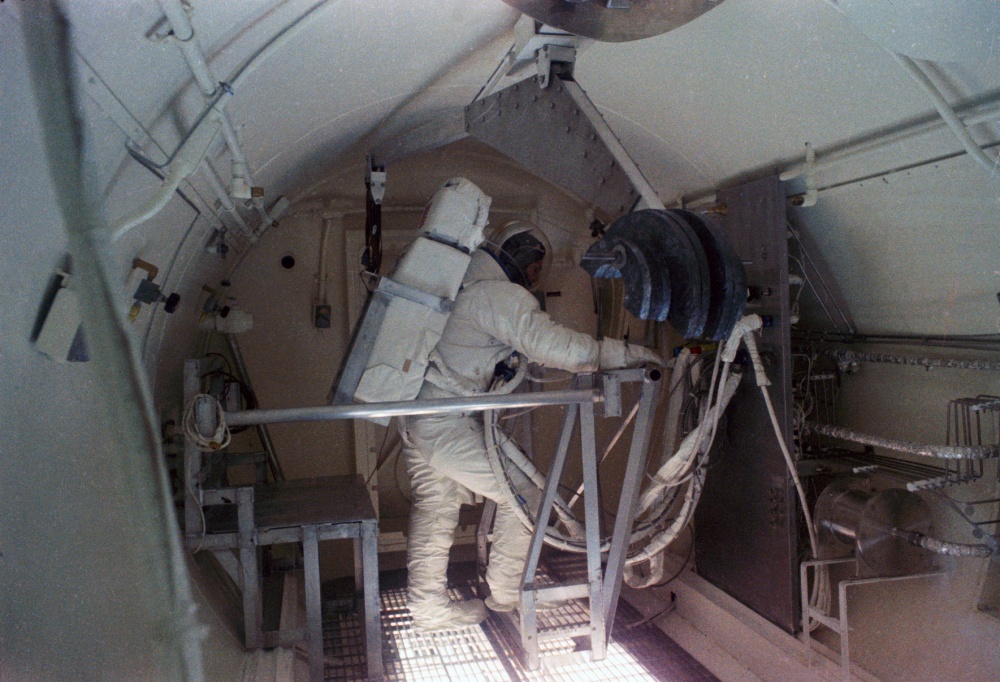

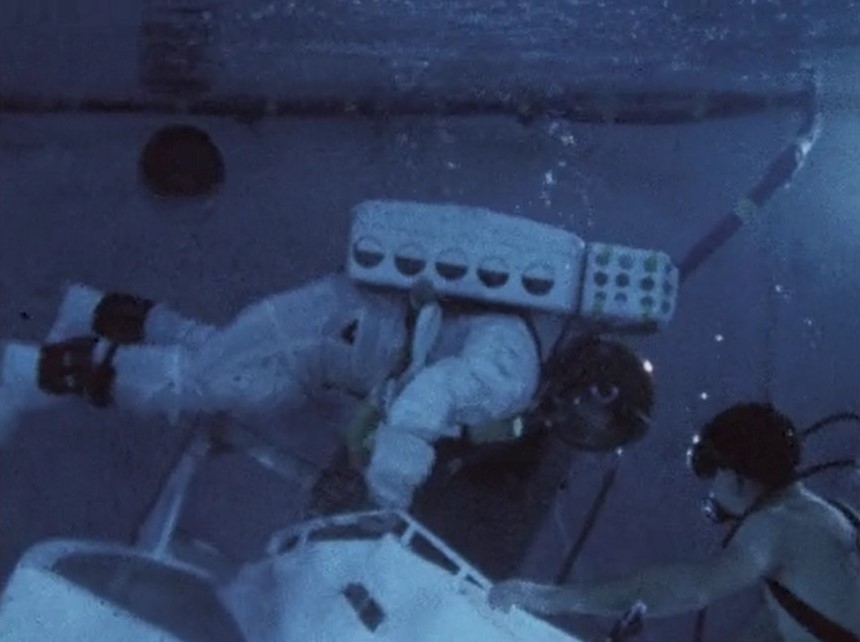

Left: In preparation for the Apollo 9 spacewalk, astronaut Russell L. Schweickart tests the Portable Life Support System backpack in an altitude chamber at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. Middle: Schweickart trains for his spacewalk in MSC’s Water Immersion Facility. Right: Apollo 9 backup astronauts Richard F. Gordon, left, and Alan L. Bean train for the spacewalk in the KC-135 zero-gravity aircraft.

Apollo 9’s 10-day mission would take place in the relative safety of low Earth orbit. After docking with the LM, the crew’s first major task involved the first spacewalk of the Apollo program and the only in-space test of the new A7L spacesuit before the Moon landing. McDivitt and Schweickart planned to enter the LM, leaving Scott in the CM. Schweickart and Scott would each perform a spacewalk from their respective spacecraft. Scott would only stand in the open CM hatch while Schweickart would exit via the LM’s front hatch onto its porch, translate over to the CM using handrails, retrieve materials samples mounted on the spacecraft’s exterior and return back to the LM, spending two hours outside. This spacewalk tested the ability of crews to transfer through open space, in case a malfunction with the tunnel or hatches between the two spacecraft prevented an internal transfer. The day after the spacewalk, McDivitt and Schweickart planned to undock the LM, leaving Scott in the CM, fly it up to 100 miles away, testing its descent and ascent stages before returning to Scott in the CM who would perform the rendezvous and docking.

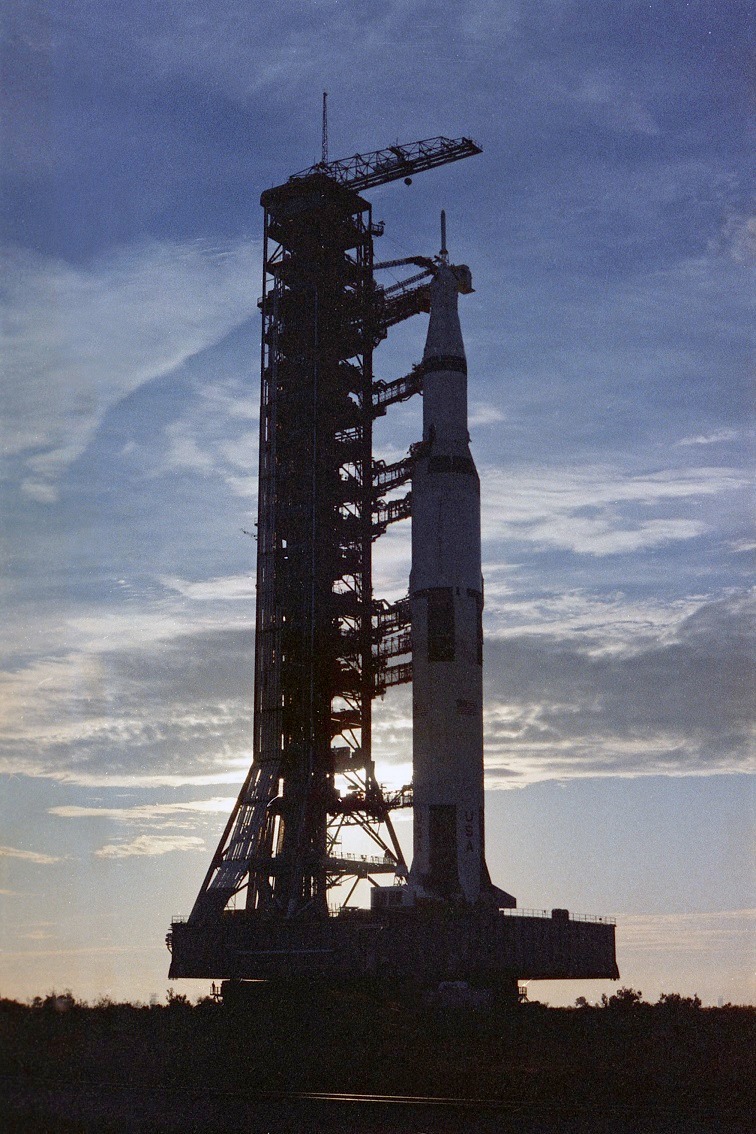

At NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, three views of the Apollo 9 rollout from the Vehicle Assembly Building to Launch Pad 39A.

The first of the three vehicles in processing flow at KSC, Apollo 9 rolled out from High Bay 3 of the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) to Launch Pad 39A on Jan. 3, just 13 days after Apollo 8 launched from the same facility, causing relatively minor damage. Stages of the Apollo 9 Saturn V had arrived at KSC during the spring and summer of 1968, the LM arrived in June and the Command and Service Modules (CSM) in October. Workers completed stacking of the Saturn V in October, adding the Apollo spacecraft in early December. On Jan. 8, NASA announced Feb. 28, 1969, as the planned launch date for Apollo 9.

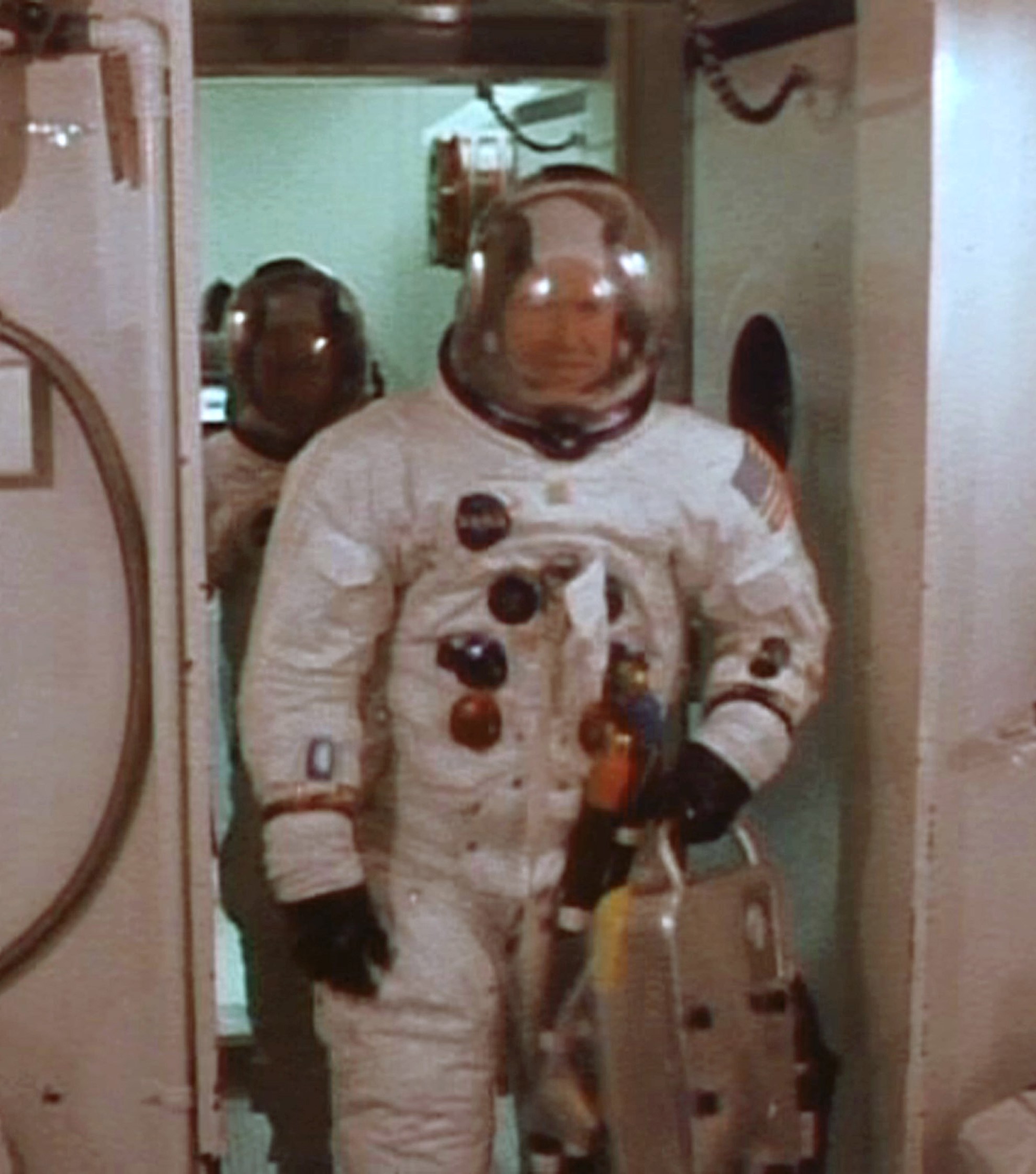

Left: Apollo 9 astronauts James A. McDivitt, front, David R. Scott, and Russell L. Schweickart depart crew quarters for the ride to Launch Pad 39A for emergency escape training. Middle: Scott, left, Schweickart, and McDivitt in the White Room during the pad emergency escape drill. Right: Scott, left, McDivitt, and Schweickart pose with their mission patch following a press conference at Grumman Aircraft and Engineering Corporation in Bethpage, New York.

Workers at the pad immediately began to prepare the vehicle for flight, including software integration tests with the Mission Control Center at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. On Jan. 15, the prime and backup crews conducted emergency egress training from their spacecraft at Launch Pad 39A. Launch controllers at KSC successfully completed the Flight Readiness Test, the final major overall test of the vehicle’s systems, between Jan. 19 and 22. During a Jan. 25 press conference at the Grumman Aircraft and Engineering Corporation in Bethpage, New York, manufacturer of the LM, the Apollo 9 astronauts provided reporters with an overview of their mission.

Apollo 10

Assuming Apollo 9 met its objectives and the LM proved space worthy in Earth orbit, in May Apollo 10 would repeat many of those tests in lunar orbit, including flying to within nine miles of the Moon’s surface.

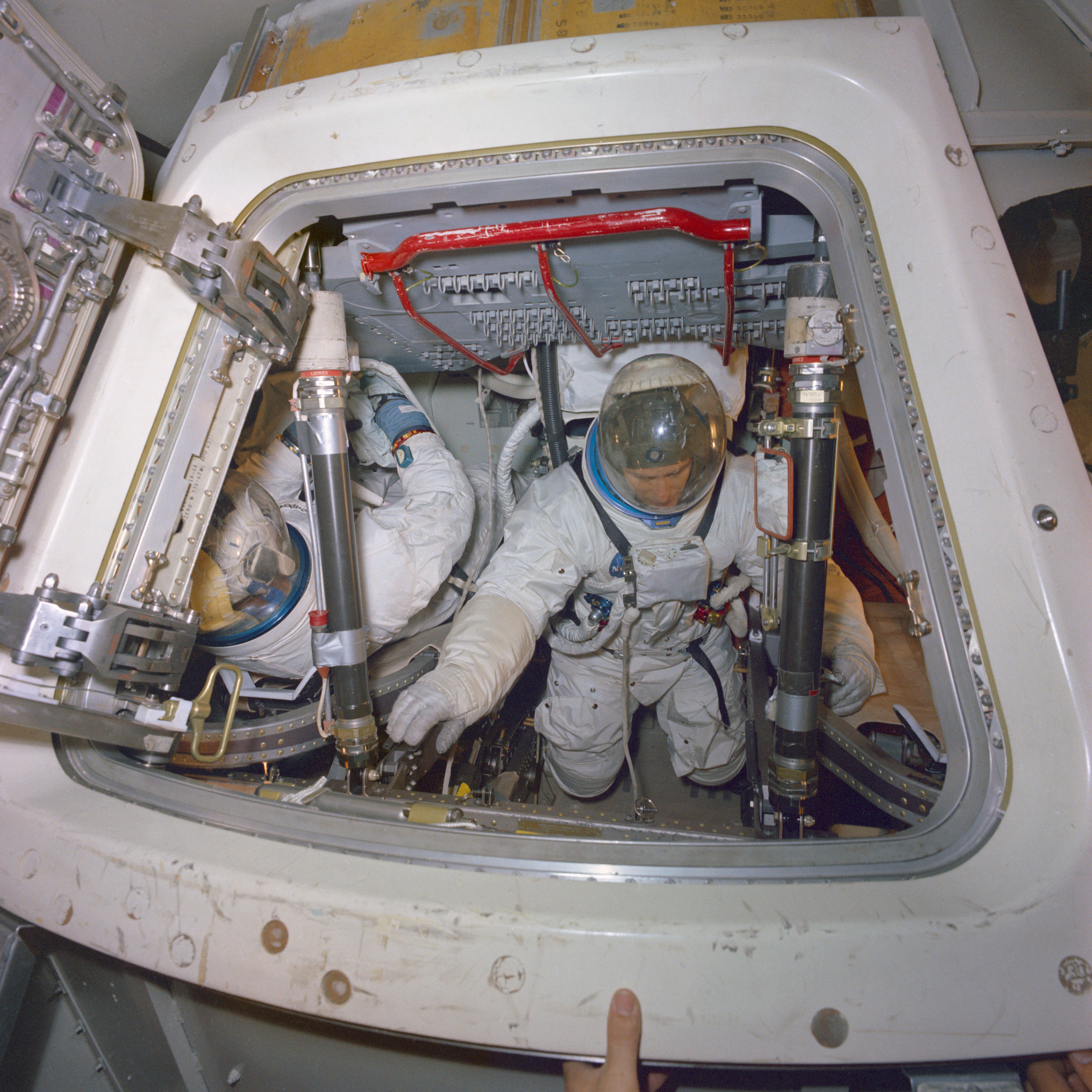

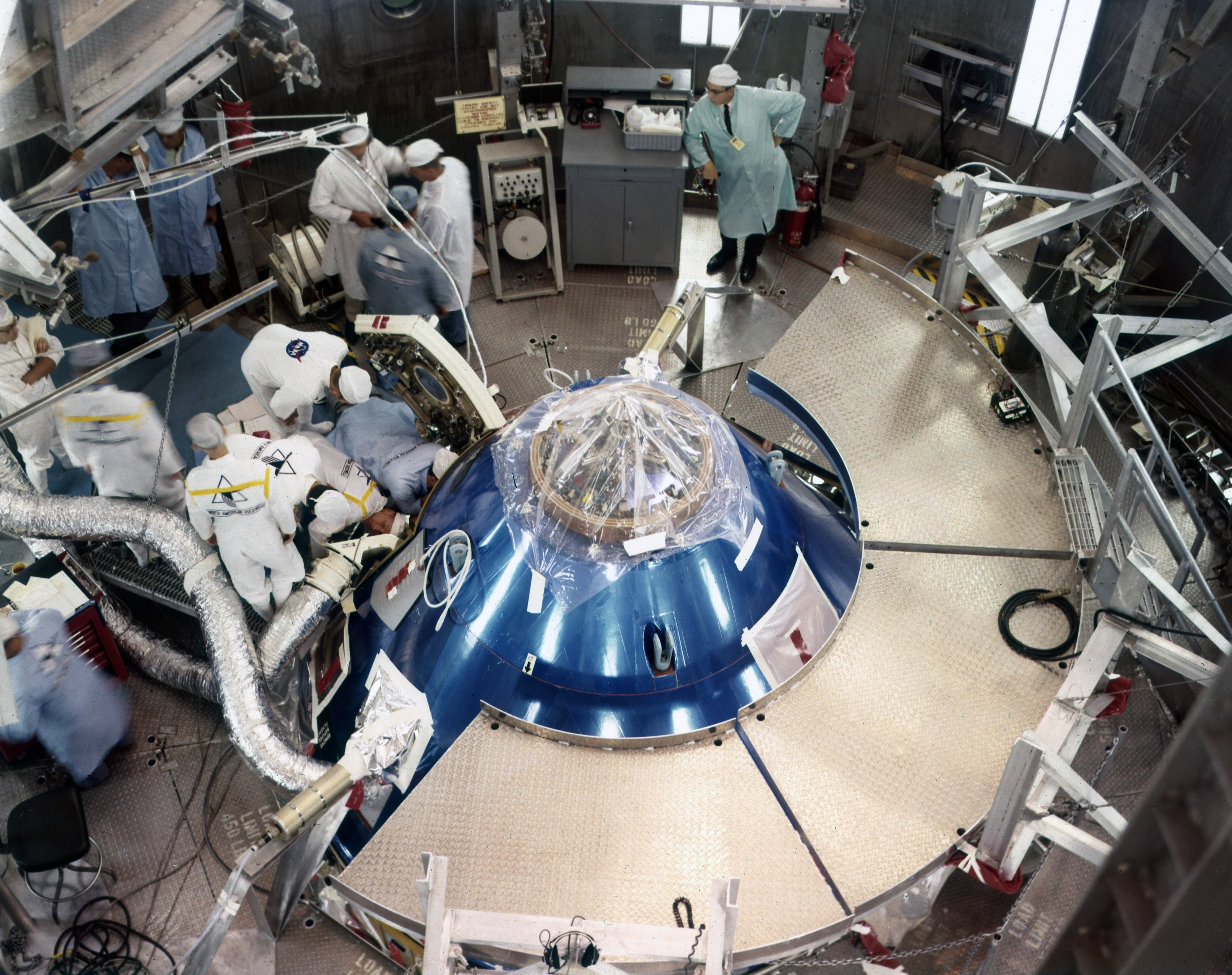

Left: Apollo 10 backup astronauts L. Gordon Cooper, front, and Edgar D. Mitchell arrive in the vacuum chamber in the Manned Spacecraft Operations Building (MSOB) at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida for a Lunar Module (LM) altitude test. Middle: Engineers in the MSOB conduct a docking test between the LM and the Command Module (CM) docking test. Right: Engineers prepare the CM for an altitude test.

In November 1968, just six months before the planned launch date, NASA officially named the Apollo 10 crew. The prime crew consisted of Thomas P. Stafford, John W. Young, and Eugene A. Cernan. All had flown Gemini missions and had recently served as the Apollo 7 backup crew. L. Gordon Cooper, Donn F. Eisele, and Edgar D. Mitchell served as their backups.

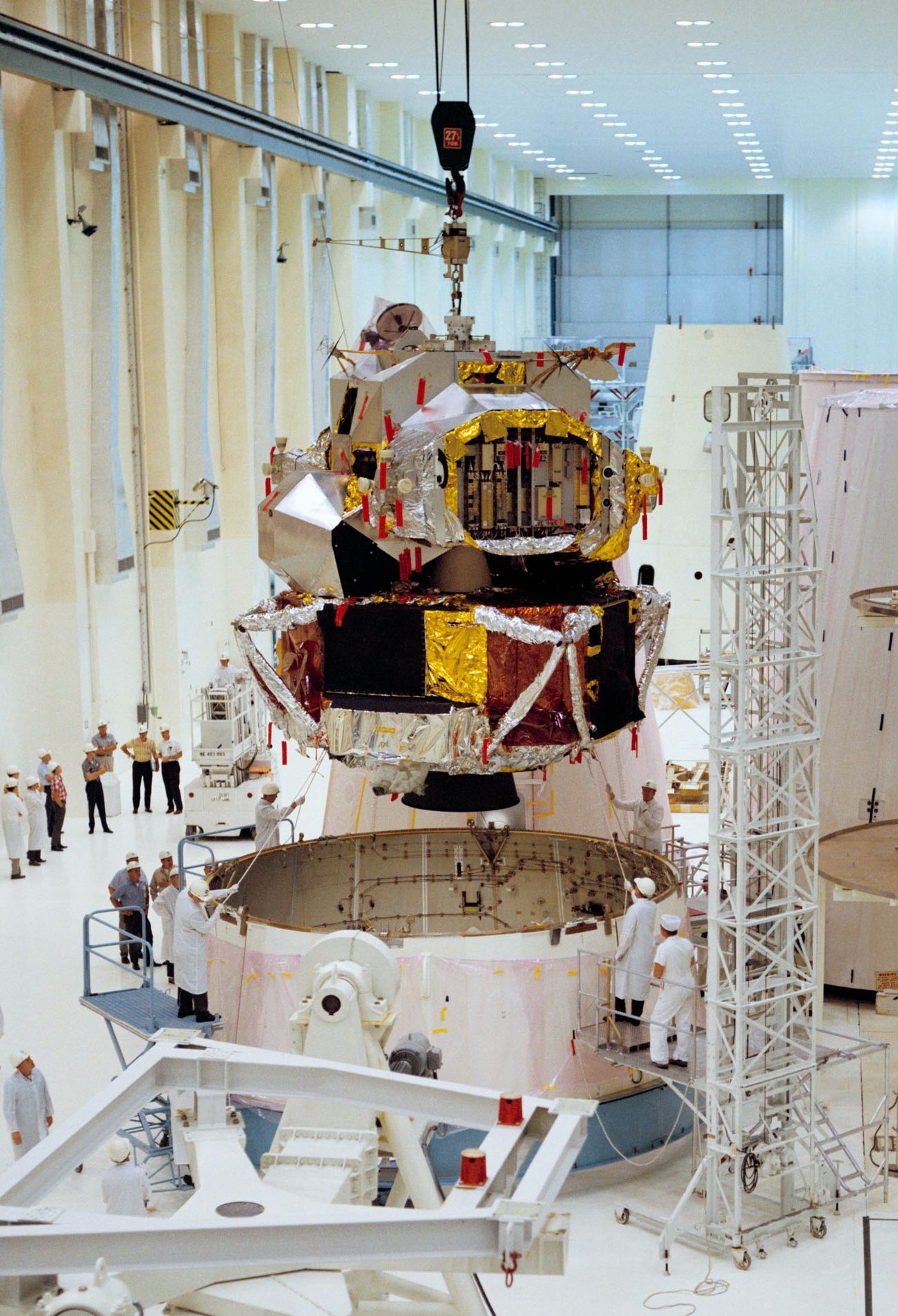

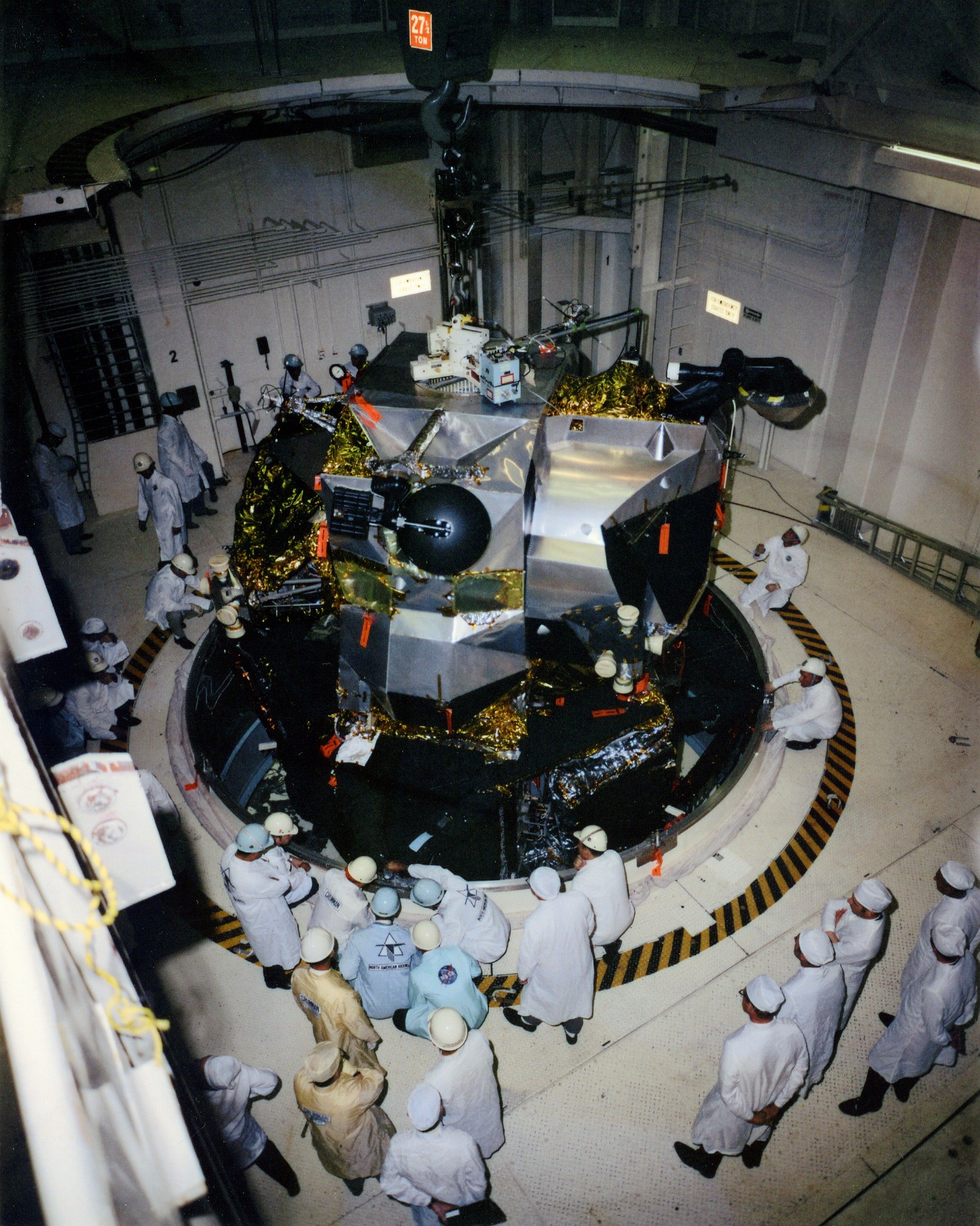

Left: In High Bay 2 of the Vehicle Assembly Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, the three stages of the Apollo 10 Saturn V await the arrival of the spacecraft. Middle left: In KSC’s Manned Spacecraft Operations Building (MSOB), workers remove the Lunar Module (LM) from an altitude chamber. Middle right: Workers in the MSOB lower the LM onto the base of the Spacecraft LM Adapter (SLA). Right: After installing the main engine bell, workers lift the Command and Service Module for mating with the SLA.

In the VAB’s High Bay 2, workers had completed stacking the Apollo 10 Saturn V’s three stages by the final days of 1968, while their colleagues prepared to roll Apollo 9’s rocket to the pad a few days later. In the nearby Manned Spacecraft Operations Building (MSOB), prime and backup crews completed altitude tests of the LM in December and workers conducted a docking test between the LM and the CM. On Jan. 16, Stafford, Young, and Cernan completed their altitude test of the CM, followed by Cooper, Eisele, and Mitchell the next day. Workers removed the spacecraft from the altitude chamber in preparation for its rollover to the VAB in early February for stacking onto the rocket.

Apollo 11

Assuming Apollo 9 and 10 accomplished their objectives, Apollo 11 would attempt the first Moon landing in July. Should Apollo 11 not succeed, NASA would try again with Apollo 12 in September and even Apollo 13 in November or December. Spacecraft and rocket manufacturers continued building components to meet that aggressive schedule.

Apollo 11 crew of Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin, left, Neil A. Armstrong, and Michael Collins.

On Jan. 9, a mere six months before the planned launch date, NASA formally announced the Apollo 11 crew, the second all-veteran three-person crew after Apollo 10 – and the last all-veteran crew until STS-26 in 1988. The next day, NASA introduced the Apollo 11 crew during a press conference at MSC. The prime crew consisted of Neil A. Armstrong, Michael Collins, and Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin. Each astronaut had flown one Gemini mission. Armstrong and Aldrin had served on the backup crew for Apollo 8 while Collins was initially a member of the prime Apollo 8 crew until a bone spur in his neck requiring surgery sidelined him. He fully recovered from the operation, and NASA included him in the Apollo 11 crew. The Apollo 11 backup crew consisted of James A. Lovell, William A. Anders, and Fred W. Haise. Lovell and Anders had just completed the Apollo 8 lunar orbit mission with Haise a backup crew member on that flight. When Anders announced that he would retire from NASA in August 1969 to join the National Space Council, Thomas K. “Ken” Mattingly began training in parallel with Anders in case the mission slipped past that date.

Left: The Lunar Module for Apollo 11 arrives at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. Middle: The Apollo 11 Command Module, left, and Service Module, in KSC’s Manned Spacecraft Operations Building shortly after their arrival. Right: The S-IVB third stage for Apollo 11’s Saturn V rocket arrives at KSC.

Hardware began to arrive at KSC for Apollo 11. With the Apollo 10 CSM still undergoing testing in the MSOB, the Apollo 11 LM’s ascent and descent stages arrived Jan. 8 and 12, respectively, followed by the CM and SM on Jan. 23. Workers in the MSOB prepared the spacecraft for vacuum chamber testing. The Saturn V’s S-IVB third stage arrived on Jan. 19. Workers trucked it to the VAB where it awaited the arrival of the first two stages, scheduled for February.

Lunar Receiving Laboratory

Left: Schematic of the Lunar Receiving Laboratory (LRL) showing its major functional areas. Right: A mockup Command Module in the spacecraft storage area, part of the Crew Reception Area, in the LRL.

With the Moon landing possibly just six months away, NASA continued to prepare key facilities designed to receive astronauts returning from the Moon. The 83,000-square-foot Lunar Receiving Laboratory (LRL), residing in MSC’s Building 37, was specially designed and built to isolate the astronauts, their spacecraft, and lunar samples to prevent back-contamination of the Earth by any possible lunar micro-organisms, and to maintain the lunar samples in as pristine a condition as possible. The building was completed in 1967, and over the next year, workers outfitted its laboratories and other facilities. A 10-day simulation in the facility in November 1968 found some deficiencies that NASA addressed promptly. On Jan. 23, 1969, workers brought a mockup Apollo CM into the LRL’s spacecraft storage area for fit checks.

Left: Workers at the Norfolk Naval Air Station in Virginia hoist the Mobile Quarantine facility (MQF) onto the USS Guadalcanal. Middle: The flexible tunnel set up between the MQF and a mockup Command Module. Right: Workers in Norfolk load the MQF onto a C-141 cargo plane for the return flight to Ellington Air Force Base in Houston.

An integral component of the back-contamination prevention process was the Mobile Quarantine Facility (MQF). Following lunar landing missions, the MQF housed astronauts and support personnel from their arrival onboard the prime recovery ship shortly after splashdown through transport to the LRL. Under contract to NASA, Melpar, Inc., of Falls Church, Virginia, converted four 35-foot Airstream trailers into MQFs, delivering the first unit in March 1968 and the last three in the spring of 1969. The first unit was used extensively for testing, with lessons learned incorporated into the later models. On Jan. 21, 1969, workers loaded the MQF aboard a U.S. Air Force C-141 cargo plane at Ellington Air Force Base near MSC to transport it to the Norfolk Naval Air Station in Virginia. Six recovery specialists from MSC spent 10 days inside the MQF, first aboard the helicopter landing-platform USS Guadalcanal (LPH-7), including attaching a flexible tunnel to a boilerplate Apollo CM, and then aboard the destroyer USS Fox (DLG-33). The overall exercise, successfully completed on Feb. 3, tested all MQF systems aboard ships and aircraft to simulate recovery operations after a lunar landing mission.

To be continued …

With special thanks to Ed Hengeveld for imagery expertise.

News from around the world in January 1969:

Jan. 7 – Congress doubles the President’s salary from $100,000 to $200,000 a year.

Jan. 9 – First test flight of the Franco-British Concorde supersonic jetliner in Bristol, U.K.

Jan. 12 – In Super Bowl III, played in Miami’s Orange Bowl, the New York Jets beat the Baltimore Colts 16 to 7.

Jan. 16 – The Soviet Union conducts the first docking between two crewed spacecraft and the first crew transfer by spacewalking cosmonauts during the Soyuz 4 and 5 missions.

Jan. 20 – Richard M. Nixon inaugurated as the 37th U.S. President.

Jan. 30 – The Beatles perform their last live gig, a 42-minute concert on the rooftop of Apple Corps Headquarters in London.