It took the Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, ocean Ecosystem (PACE) mission just 13 minutes to reach low-Earth orbit from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in February 2024. It took a network of scientists at NASA and research institutions around the world more than 20 years to carefully craft and test the novel instruments that allow PACE to study the ocean and atmosphere with unprecedented clarity.

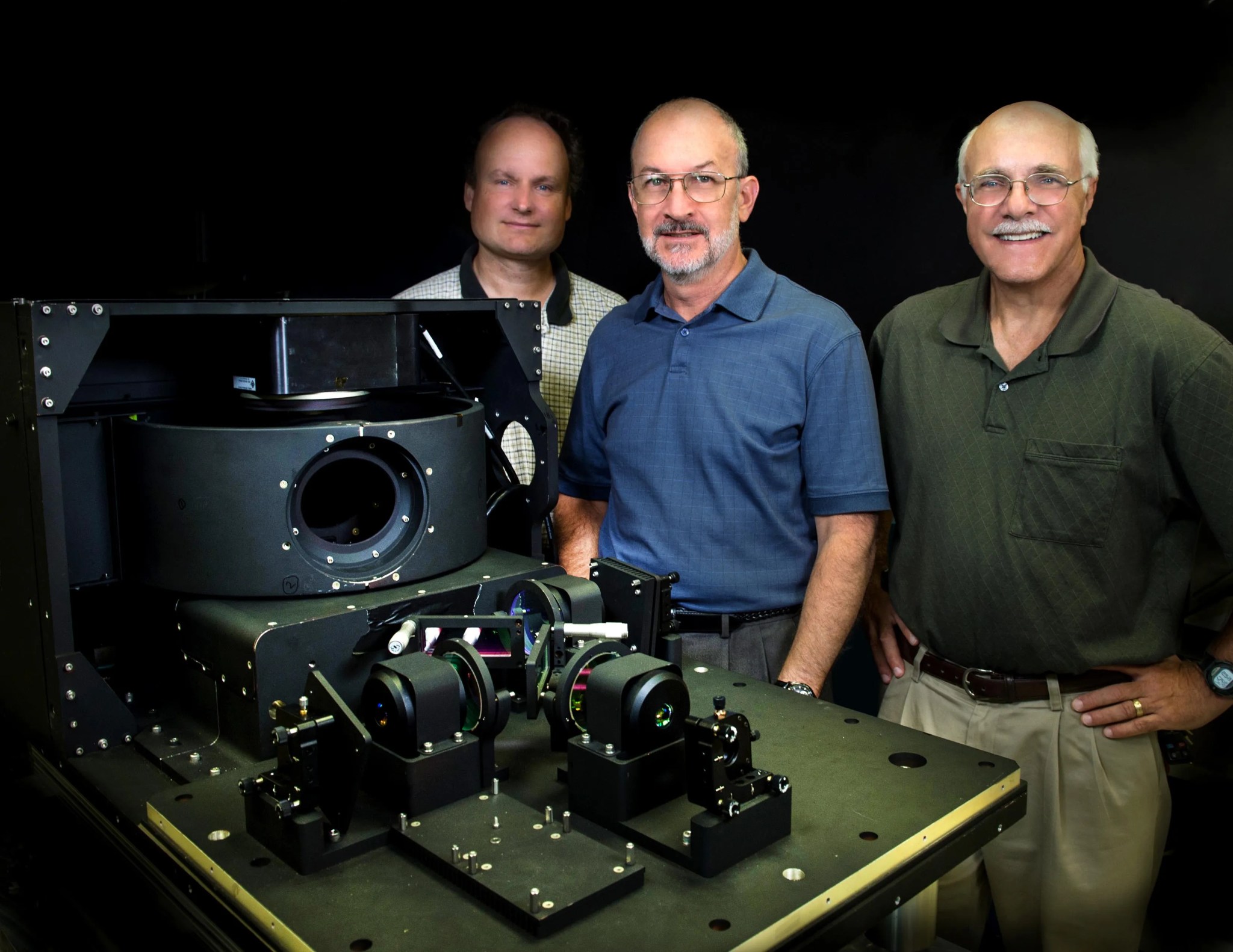

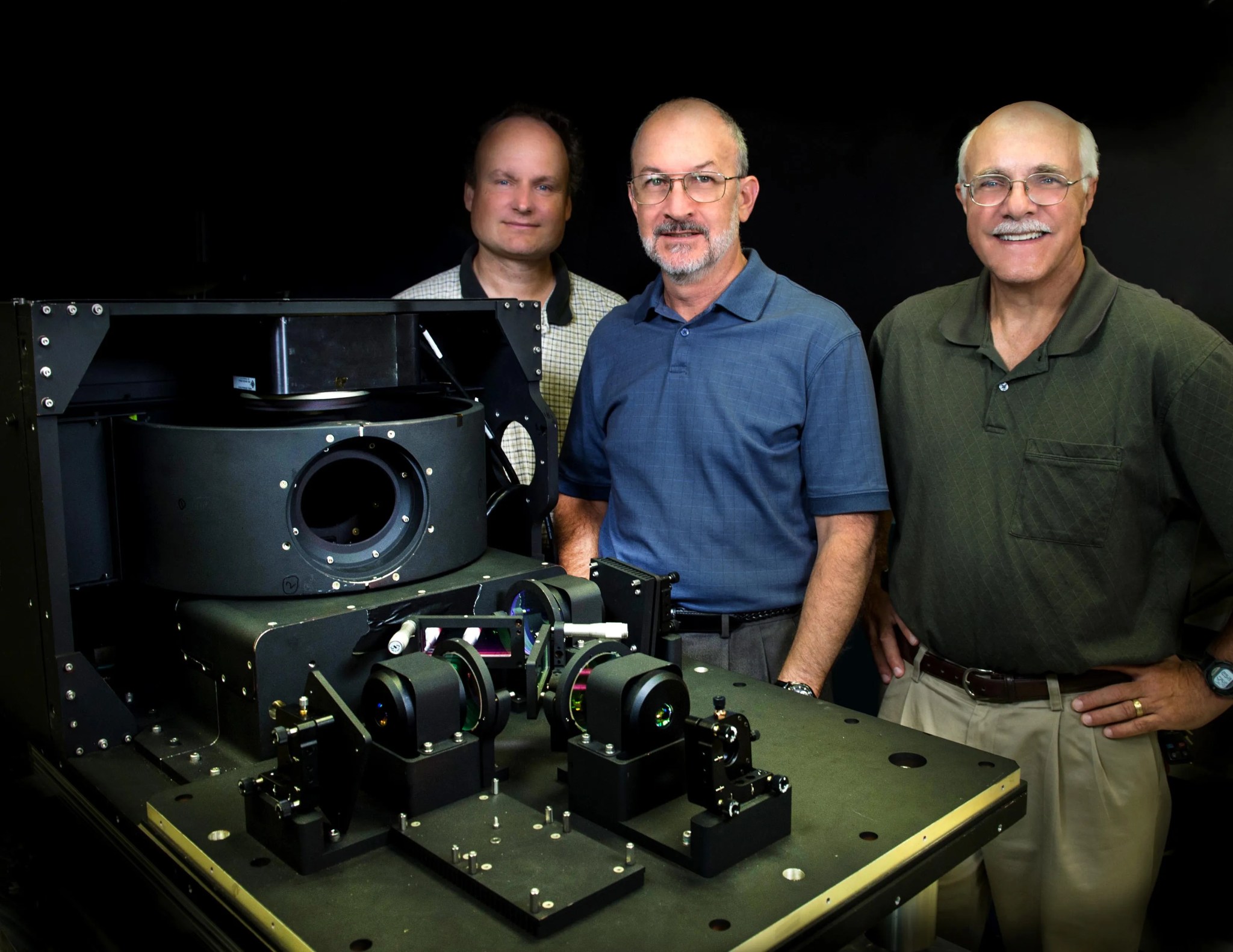

In the early 2000s, a team of scientists at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, prototyped the Ocean Radiometer for Carbon Assessment (ORCA) instrument, which ultimately became PACE’s primary research tool: the Ocean Color instrument (OCI). Then, in the 2010s, a team from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC), worked with NASA to prototype the Hyper Angular Rainbow Polarimeter (HARP), a shoebox-sized instrument that will collect groundbreaking measurements of atmospheric aerosols.

Neither PACE’s OCI nor HARP2 — a nearly exact copy of the HARP prototype — would exist were it not for NASA’s early investments in novel technologies for Earth observation through competitive grants distributed by the agency’s Earth Science Technology Office (ESTO). Over the last 25 years, ESTO has managed the development of more than 1,100 new technologies for gathering science measurements.

“All of this investment in the tech development early on basically made it much, much easier for us to build the observatory into what it is today,” said Jeremy Werdell, an oceanographer at NASA Goddard and project scientist for PACE.

Charles “Chuck” McClain, who led the ORCA research team until his retirement in 2013, said NASA’s commitment to technology development is a cornerstone of PACE’s success. “Without ESTO, it wouldn’t have happened. It was a long and winding road, getting to where we are today.”

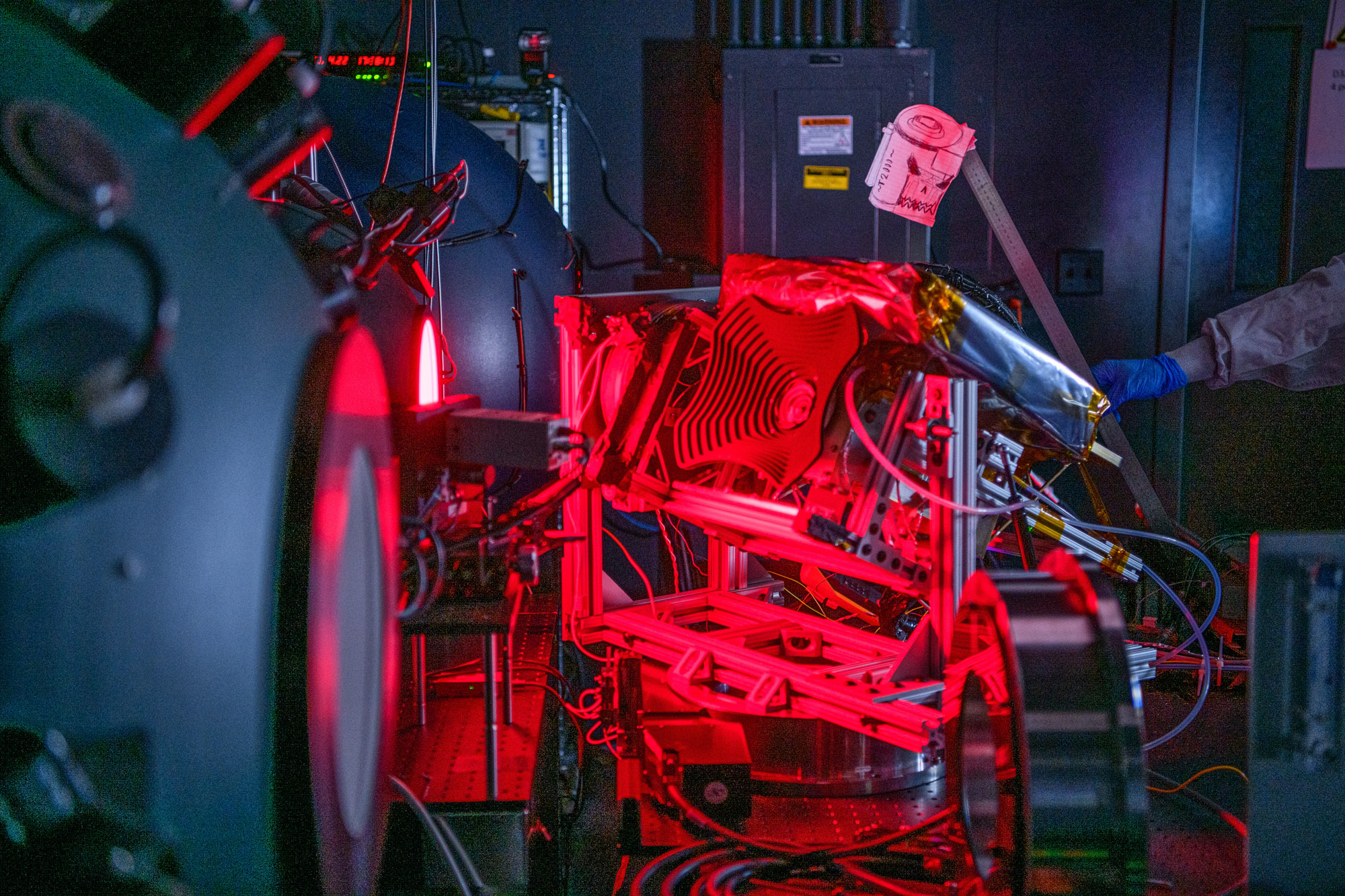

It was ORCA that first demonstrated a telescope rotating at a speed of six revolutions per second could synchronize perfectly with an array of charge-coupled devices — microchips that transform telescopic projections into digital images. This innovation made it possible for OCI to observe hyperspectral shades of ocean color previously unobtainable using space-based sensors.

But what made ORCA especially appealing to PACE was its pedigree of thorough testing. “One really important consideration was technology readiness,” said Gerhard Meister, who took over ORCA after McClain retired and serves as OCI instrument scientist. Compared to other ocean radiometer designs that were considered for PACE, “we had this instrument that was ready, and we had shown that it would work.”

Technology readiness also made HARP an appealing solution to PACE’s polarimeter challenge. Mission engineers needed an instrument powerful enough to ensure PACE’s ocean color measurements weren’t jeopardized by atmospheric interference, but compact enough to fly on the PACE observatory platform.

By the time Vanderlei Martins, an atmospheric scientist at UMBC, first spoke to Werdell about incorporating a version of HARP into PACE in 2016, he had proven the technology with AirHARP, an airplane-mounted version of HARP, and was using an ESTO award to prepare HARP CubeSat for space.

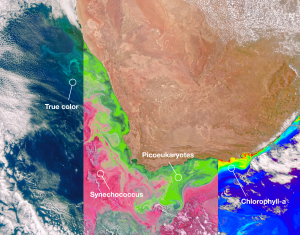

HARP2 relies on the same optical system developed through AirHARP and HARP CubeSat. A wide-angle lens observes Earth’s surface from up to 60 different viewing angles with a spatial resolution of 1.62 miles (2.6kilometers) per pixel, all without any moving parts. This gives researchers a global view of aerosols from a tiny instrument that consumes very little energy.

Were it not for NASA’s early support of AirHARP and HARP CubeSat, said Martins, “I don’t think we would have HARP2 today.” He added: “We achieved every single goal, every single element, and that was because ESTO stayed with us.”

That support continues making a difference to researchers like Jessie Turner, an oceanographer at the University of Connecticut who will use PACE to study algal blooms and water clarity in the Chesapeake Bay.

“For my application that I’m building for early adopters of PACE data, I actually think that polarimeters are going to be really useful because that’s something we haven’t fully done before for the ocean,” Turner said. “Polarimetric data can actually help us see what kind of particles are in the water.”

Without the early development and test-drives of the instruments from McClain’s and Martins’ teams, PACE as we know it wouldn’t exist.

“It all kind of fell in place in a timely manner that allowed us to mature the instruments, along with the science, just in time for PACE,” said McClain.

To explore current opportunities to collaborate with NASA on new technologies for studying Earth, visit ESTO’s open solicitations page here.

By Gage Taylor

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.