RAPA NUI (EASTER ISLAND), Chile — Eclipse-chasers from across the globe gathered on remote Rapa Nui — also known as Isla de Pascua and Easter Island — to witness a fabulous “ring of fire” annular solar eclipse for about six minutes. It was the island’s first in 236 years and last for 321 years.

I was there with eclipse-chaser experts Astro Trails, who I joined in Santiago, Chile to take a five-hour flight to the tiny Chilean island, 1,200 miles (1,931 kilometers) east of Pitcairn Island and 2,200 miles (3,540 km) from Chile. As I stepped off the plane, I could see extinct volcanoes and grassland. Within minutes, a necklace of flowers was placed around my neck. It was then a short 10-minute bus ride to the capital, Hanga Roa. The entire island is just 63 square miles (163 square km).

Related: In photos: Annular solar eclipse 2024 delights with stunning ‘ring of fire’ display

It’s famous for its 900 or so moai, giant stone monoliths carved between 1150 and 1290 that look solemnly inwards from the coast. After a few days of photographing the moai across the island in partly cloudy conditions, every one of the 59 guests — and the dozens of other eclipse chasers in Hanga Roa’s low-rise resorts and hostels — knew that eclipse day would be nail-biting.

Would we see the ring or be denied by a passing cloud? To make matters worse, a tropical storm to the island’s southeast looked to be approaching. There was also some uncertainty about where visitors would be allowed to watch it. Local elections were held recently, and a new board of the park administration had only recently been formed to work on regulations and restrictions for Oct. 2. With the 13 archaeological sites in Rapa Nui National Park unreliable observing sites, Astro Trails had hired Parcela Mahinatur farm to watch the three-and-a-half hour event. It was to occur precisely one lunar year after an annular solar eclipse I witnessed in New Mexico’s Chaco Canyon, home to a sun-watching culture between AD 850 and 1250.

We arrived an hour before the eclipse and settled in, with photographers assessing how strong the wind was whipping through the site. One imager, Stephen Bedingfield from Canada — a veteran of 12 totals and 6 annulars — collected a few logs from a nearby log pile and hung them in a bag from his tripod to keep it as still as possible. Rapa Nui has plenty of weather, and despite spring in the southern hemisphere, it was just 59 degrees Fahrenheit (15 degrees Celsius). It felt colder, the wind freezing my fingers as I placed a solar filter on a ZWO SeeStar S50 smart telescope to take images of the partially eclipsed sun.

Within minutes, a light rain swept across the farm, but minutes later, there was a clear sky. Coats on, coats off. As the beginning of the partial phase — 12:23 p.m. local time — approached, eclipse glasses were given out. Tony West from Yorkshire, England, provided the countdown. Within a few seconds, I could see the new moon beginning to move in front of the sun‘s left-hand side. First contact!

The next three hours, 28 minutes and 34 seconds were spent watching the moon cover sunspots one by one, taking images on the Seestar, and hoping that the banks of cloud coming in from the Pacific Ocean would either hurry up or stay put. I tried to eat lunch, but after a few mouthfuls, I returned to observing the sun and operating the SeeStar. I was too excited. To be in the path of a central solar eclipse is so rare.

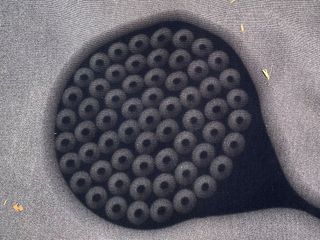

I projected “smiley face” crescent sun silhouettes using my well-traveled spaghetti spoon while another eclipse chaser used a Sunspotter to project a crisp magnified image of the eclipse onto a piece of paper.

With the eclipse about two-thirds to annularity, the temperature dropped sharply, and the green fields around took on a more pronounced color. As we got close to the “ring of fire,” shadows became fuzzy at the edges, and it got very cold. The wind stopped. The cloud covering the sun and moon moved away. At 2:03 p.m. I saw Baily‘s beads fizzing around the point where the moon‘s incoming limb met the sun’s edge, but only for about 10 seconds before the “ring of fire” appeared. Second contact — what a sight!

Even after observing dozens of solar eclipses, to think that the sun and moon can come to such a perfect alignment still brought me peace and a sense of beauty unmatched by any other sight in nature. But there was one image I wanted more than the “ring of fire” — ringlets. Using a spaghetti spoon during partial phases, it’s possible to project crescent suns, but only in the precious short minutes of annularity it is possible to project ringlets. It’s an image I’d not captured before.

After I’d snapped a few images, I returned to the eclipse, observing the moon, which appeared to stay completely still for a few minutes. The ring was never perfect — such a thing can only be seen from the centerline of an eclipse path — but its slight imperfection made it all the more eery-looking. Baily’s beads returned as the edge of the moon touched the edge of the sun. Third contact! A few cheers went up and a few hand-claps. Not a minute later, a horned sun just out of annularity was hidden by a cloud. We had been incredibly lucky — and in more ways than one.

Central solar eclipses on Easter Island are very rare. Remarkably, there was a total on Jul. 11, 2010, just over 14 years ago, but before that, it was 1788. The next one is in 2324. After watching any solar eclipse, the most common question is, “When’s the next one?” Not in this group. Everyone here knew that the next total is on Aug. 12, 2026. As for my next date with a “ring of fire,” I’ve got Feb. 6, 2027, circled on my calendar to be in Ghana to watch one just before sunset. It will struggle to be as dramatic or as beautiful as Easter Island’s exquisite annular.

This article was made possible with travel from Santiago, Chile supported by a press trip with AstroTrails.