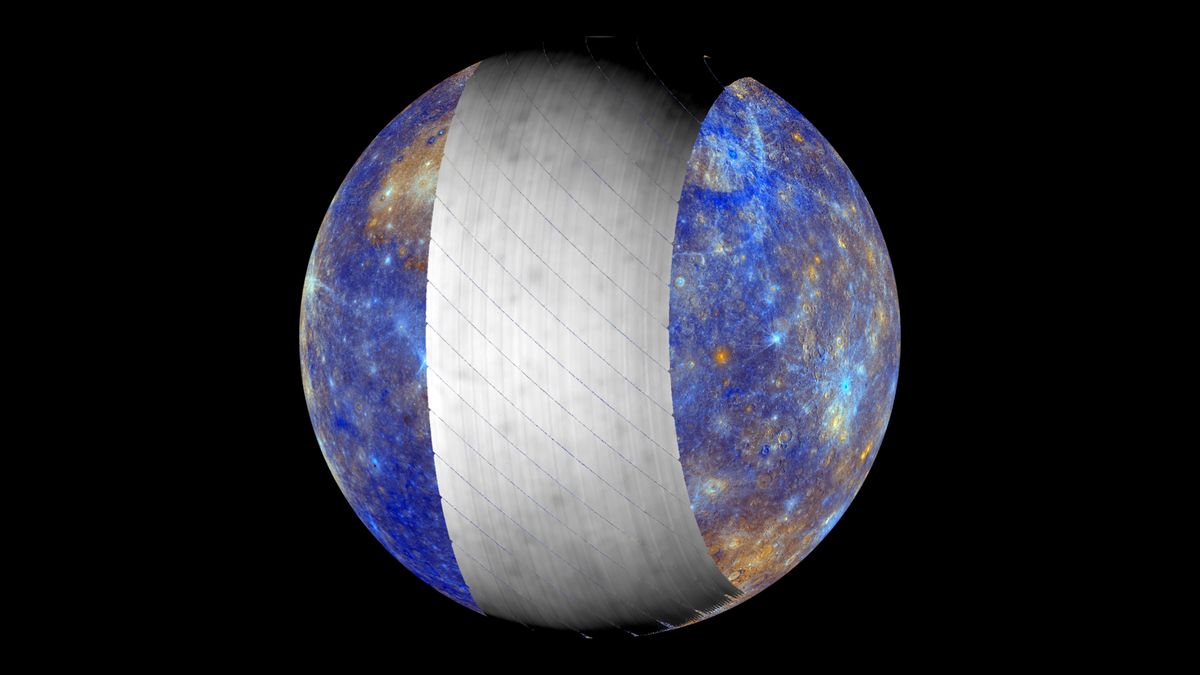

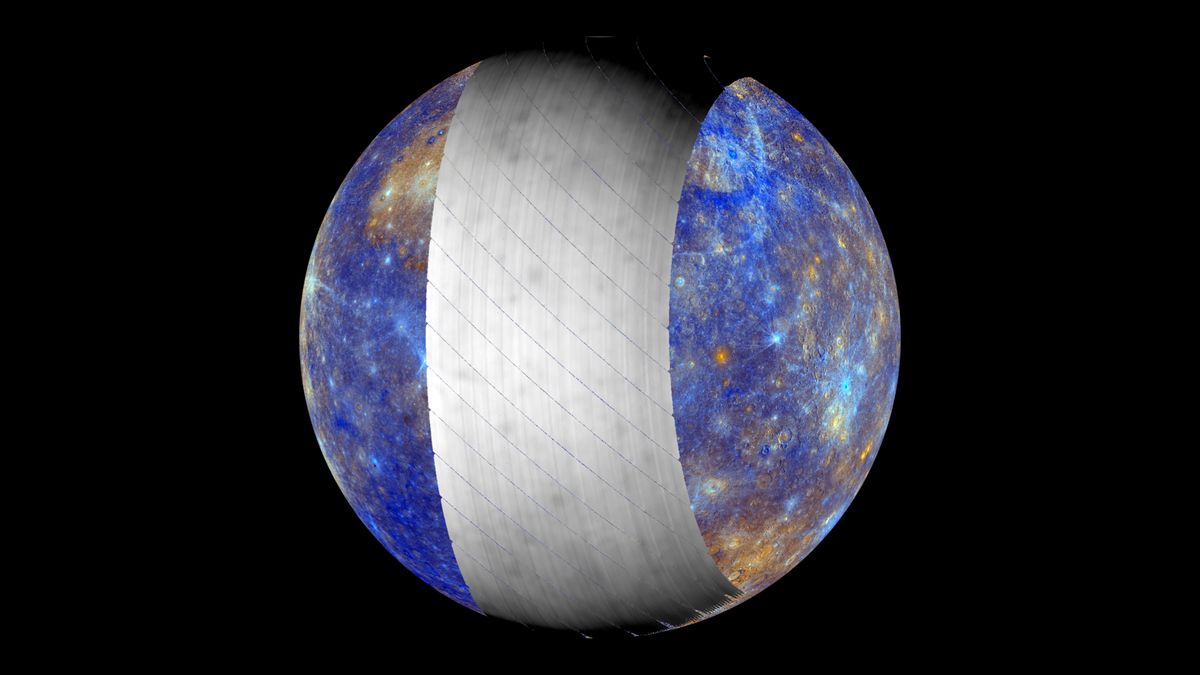

BepiColombo just imaged Mercury in a whole new light — mid-infrared light, to be precise.

On the spacecraft’s fifth flyby of Mercury earlier this month (out of a planned six flybys) BepiColombo pointed its Mercury Radiometer and Thermal Infrared Spectrometer (MERTIS) at a swath of Mercury’s northern hemisphere. Mid-infrared light is invisible to human eyes, but it carries a wealth of information about the mineral makeup and temperature of very hot rocks like those on Mercury’s sun-baked surface. The Dec. 1 flyby marked the first time scientists have ever seen Mercury’s surface in mid-infrared wavelengths, and the new view reveals some tantalizing hints about the planet’s geology.

BepiColombo swooped past Mercury at a distance of 37,626 kilometers (about 23,400 miles) on Dec. 1. The most recent flyby isn’t the spacecraft’s closest encounter with Mercury; that happened on Sept. 4, when the spacecraft skimmed just 165 kilometers (103 miles) above Mercury’s battered, scorched surface. When BepiColombo settles into orbit around Mercury in late 2026, it will pass within 590 kilometers (370 miles) of the planet at its closest point before swinging back out to 11,640 kilometers (7,230 miles). But to get there, the spacecraft has taken a spiraling route through the inner solar system, using the gravitational tug of Earth (once), Venus (twice), and Mercury (six times) to get itself on the right course at the right speed to end up in orbit around Mercury.

Those six Mercury flybys, the last of which will happen in January 2025, together offer researchers a chance to test out the spacecraft’s instruments and gather scientific data that will help them refine their plan for the science BepiColombo will do while in orbit. One of the big questions scientists hope to answer about Mercury in the coming years is exactly what its surface is made of — and what that tells us about how the planet formed and evolved so perilously close to the sun’s heat and gravity. MERTIS is the instrument they hope will shed new (mid-infrared) light on that subject, because most of the minerals that combine to form rocks tend to radiate brightly in the mid-infrared wavelengths when they’re very hot.

You may like

For the last two decades, MERTIS’s science team has heated minerals, and combinations of minerals, to more than 400 degrees Celsius (752 degrees Fahrenheit) in the lab, then measured the mid-infrared radiation they emit. The result is a database of glowing fingerprints for several minerals, which the science team can compare to the MERTIS data to identify what different patches of Mercury’s surface are made of, how hot they are, and how rough the terrain is.

“Because Mercury’s surface is surprisingly poor in iron, we have been testing natural and synthetic minerals that lack iron,” said Solmaz Adeli of the German Aerospace Center, project lead for the latest flyby, in a statement. “The materials tested include rock-forming minerals to simulate what Mercury’s surface might be made of.”

The latest flyby, MERTIS’s first chance to shine, captured a swath of Mercury’s northern hemisphere, including part of a wide volcanic plain and part of the Caloris Basin: a rocky plain inside a large impact crater, which, on every other orbit, passes directly beneath the sun while Mercury is at its closest point to our star. These images also contain a striking view of Bashō Crater, an impact crater previously photographed by the Mariner 10 (1974-1975) and Messenger (2011-2015) spacecraft.

RELATED STORIES:

“The moment when we first looked at the MERTIS flyby data and could immediately distinguish impact craters was breathtaking!” said Adeli. “There is so much to be discovered in this dataset – surface features that have never been observed in this way before are waiting for us.”

From more than 37,600 kilometers (23,363 miles) away, MERTIS was able to image Mercury’s surface with a relatively low resolution of 26 kilometers to 30 kilometers (16 miles to 19 miles) — enough to give the science team a broad overview, but not much detail about the planet’s rocky geological history. Once BepiColombo finally settles into orbit, MERTIS will map the whole surface at a resolution of 500 meters (547 yards).