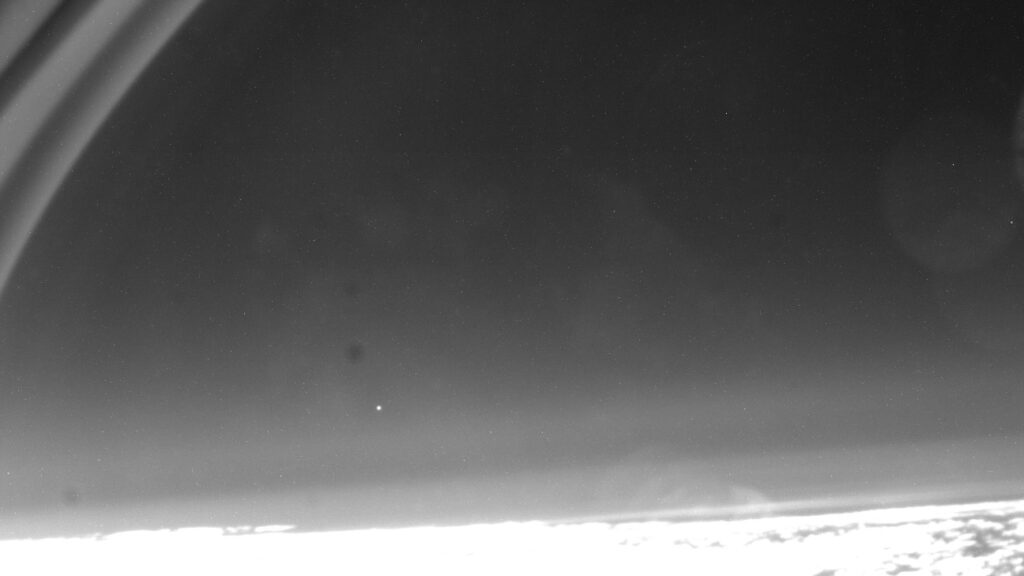

A stunning new image from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is allowing astronomers to examine the complex and turbulent final stages of a dying star’s life.

The snapshot above showcases NGC 1514, a planetary nebula that resides roughly 1,500 light-years from Earth in the constellation Taurus. Despite the term, however, NGC 1514 has nothing to do with planets. Instead, at its heart, there are two stars.

These stars appear as a single point of light in the James Webb Space Telescope‘s view, and this point of light is encircled by an arc of orange dust. Of particular interest to astronomers is the nebula’s faint, Venn-diagram-like structure — two rings of ejected material shaped by the gravitational influence of the central stars. Scientists say the rings offer a unique opportunity to dissect the complex interplay of stellar outflow over eons.

“Before Webb, we weren’t able to detect most of this material, let alone observe it so clearly,” Mike Ressler, a project scientist for the JWST’s MIRI instrument who discovered the rings in 2010 using a different NASA telescope, said in a statement. “With MIRI’s data, we can now comprehensively examine the turbulent nature of this nebula.”

Previous observations of the binary system showed that the nine-year orbit of these two stars is one of the longest known for any planetary nebula. Astronomers suspect the nebula’s formation was primarily driven by the more massive of the two stars. As that star aged, it likely underwent a dramatic expansion, shedding layers of gas and dust through its stellar wind and leaving behind a hot, compact core known as a white dwarf.

The faster, weaker winds emanating from this white dwarf likely swept up the earlier, slower-moving material, forming clumpy, filamentary rings that are extremely faint and only visible in infrared light, according to the statement. The JWST’s view also reveals a network of holes close to the central stars where faster-moving material punched through the slower, denser outer layers of ejected gas and dust.

“When this star was at its peak of losing material, the companion star could have come exceptionally close,” David Jones, a senior scientist at the Institute of Astrophysics on the Canary Islands, who proved there is a binary star system at the center of this planetary nebula in 2017, said in the statement. “That interaction can lead to shapes that you wouldn’t expect — instead of producing a sphere, this interaction might have formed these rings.”

The two rings appear unevenly illuminated and textured in the JWST’s data, likely composed of very small dust grains that are slightly heated by ultraviolet light emanating from the central white dwarf.

“When those grains are hit by ultraviolet light from the white dwarf star, they heat up ever so slightly, which we think makes them just warm enough to be detected by Webb in mid-infrared light,” Ressler said in the statement.

The JWST’s observations also detected oxygen in the nebula’s clumpy pink center, but carbon as well as complex molecules like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons — typically expected in such nebulas — were notably absent. According to the statement, the long orbital period of the central binary stars may be responsible, as the extended orbit could have stirred the expelled material, preventing the formation of these more complex compounds.

Related Stories:

The remarkable detail provided by observations like these has made the $10 billion JWST, NASA’s largest and most powerful space telescope, more in demand than ever before, with astronomers requesting the equivalent of nine years’ worth of observing time with the telescope in one operational year. This intense demand comes at a challenging time, however, as the JWST faces potential budget cuts of up to 20% despite being only halfway through its primary mission. These cuts, expected to take effect later this year, would impact all aspects of the observatory’s work, from proposal reviews and data analysis to anomaly resolution and community engagement.

“Frankly, this mission works far better than, really, most folks expected it to, you know,” Tom Brown, who leads the JWST mission office at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Maryland, had told scientists during a town hall event in January at the annual American Astronomical Society conference. “It’s extremely worrisome that, while we’re in the middle of the prime mission, we’re also maybe looking at significant budget cuts.”

These observations are also described in a paper published April 2 in The Astronomical Journal.