Earlier this year, an underwater detector in the Mediterranean Sea found the most energetic neutrino to date. And scientists are still talking about it because, well, this discovery could be a really big deal. Not only could this neutrino, also known as a “ghost particle,” have been fleeing a gamma-ray burst or a supermassive black hole, but it could also have been produced by an ultra-powerful cosmic ray interacting with the cosmic microwave background (CMB).

That latter bit which we’ll get to soon, could be huge. Moreover, the detector that pinpointed this particle isn’t even totally built yet — once put together, who knows what it can accomplish. “We’re excited to have observed this event and we’re hungry and curious for more,” KM3NeT’s spokesperson, Paul de Jong of the University of Amsterdam, told Space.com

For some background, the neutrino was detected on February 13, 2023 by the European Union-funded KM3NeT, the Cubic Kilometre Neutrino Telescope. Neutrinos are ghostly particles because they have very little mass and rarely interact with other forms of matter, making them very difficult to detect. Trillions of neutrinos are passing through your body every second, yet you cannot tell. Scientists have to be patient to spot even one neutrino.

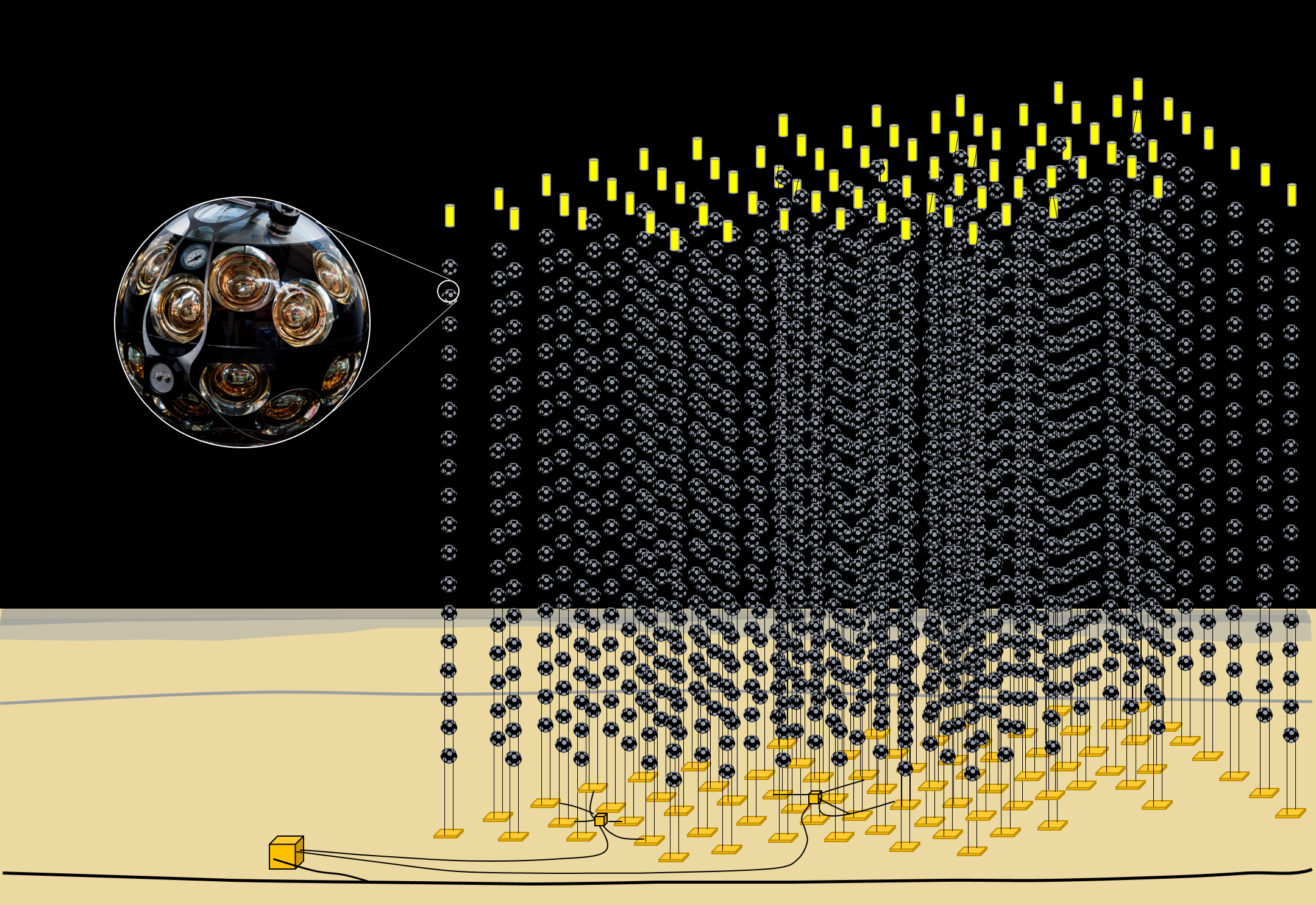

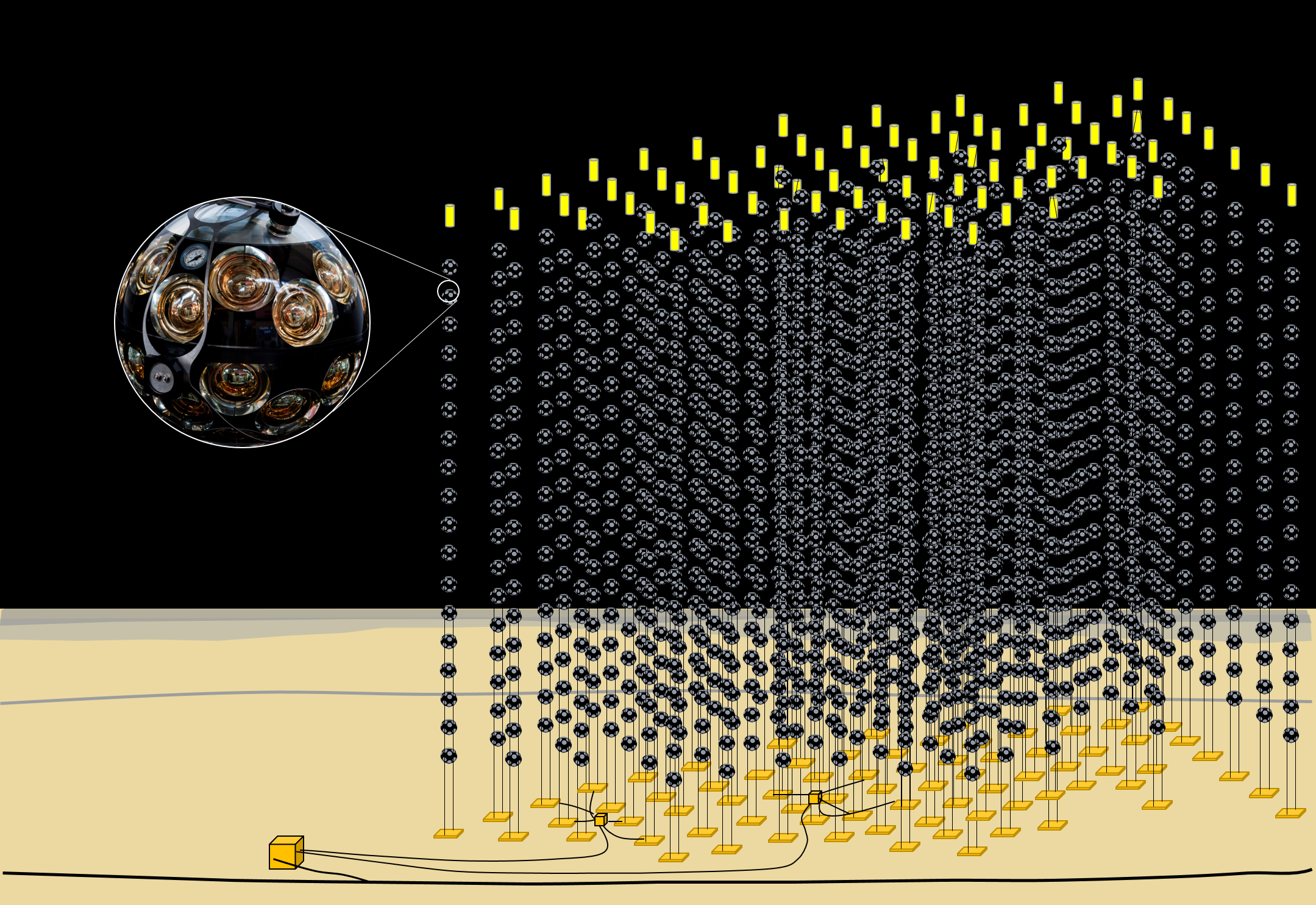

Modern neutrino detectors are placed in water, and particularly in the dark. Sometimes that water is held in a tank, as was the case with the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory in Canada, as well as with Super-Kamiokande in Japan. Other times, that water is frozen in the ground, as in the case of the IceCube Neutrino Observatory at the South Pole. But it’s also possible for neutrino detectors to literally be dipped into the sea, as is the case with KM3NeT, which extends as deep as 2.17 miles (3.5 kilometers) below the waves.

The reason water is so important is that, occasionally, a neutrino will interact with a molecule of water. The energies involved can be so great that the collision smashes the water molecule apart into a bunch of daughter nuclei and particles, specifically muons. The muons travel quickly, almost as fast as light in a vacuum, and definitely faster than light through water — the refractive index of water slows light down to approximately 738,188,976 feet per second (225,000,000 meters per second) compared to 983,571,056 feet per second (299,792,458 meters per second) in a vacuum. Because the muons travel faster than light in water, they give off the equivalent of a sonic boom in the form of a flash of light. This light is called Cherenkov radiation.

KM3NeT consists of two detectors. The first, called ORCA, is 8,038 feet (2,450 meters) deep off the coast of France and is designed to study how neutrinos oscillate between different types of neutrinos. The other, aka the detector that spotted the new energetic neutrino — which has been catalogued as KM3-230213A — is called ARCA and is located off the coast of Sicily.

Both ARCA and ORCA are still under construction. When complete, ARCA will feature 230 vertical detection lines descending into the sea. Each will be lined with 18 optical modules containing 31 photomultiplier tubes that can spot flashes of Cherenkov radiation in the darkness at those depths. At the time that ARCA detected KM3-230213A, only 21 of its detection lines were in operation.

The muon ARCA detected had an energy of 120 PeV (1,000 trillion, or quadrillion, electronvolts), which implies the neutrino that produced it must have had a record-breaking energy of 220 PeV. This is 100 quadrillion times more energetic than visible-light photons, and 30 times more energetic than the neutrino that held the previous energy record.

Muons can travel several miles through the sea before being absorbed, and KM3NeT detected the muon traveling horizontally rather than straight down to the sea floor.

“The horizontal direction on the muon is very relevant,” said de Jong.

Muons can also be formed in cosmic-ray spallation, wherein a cosmic ray enters Earth’s atmosphere and collides with a molecule or atom, smashing it apart into a shower of subatomic particles. Muons formed in this manner can either reach the surface or enter the ocean while traveling straight down — not horizontally. To have been moving horizontally, the muon must have instead “been created close to the detector, and the only realistic scenario is that it was created by a high-energy neutrino,” said de Jong.

A neutrino of 220 PeV is unprecedented. No environment or object known in our Milky Way galaxy could have produced a neutrino with so much energy. That means its origin must be extragalactic, perhaps created in the violence of a star exploding and producing a gamma-ray burst, or a supermassive black hole ripping a star or gas cloud to shreds with its titanic gravitational tidal forces. Because neutrinos are not deflected by magnetic fields or by gravity, their direction of travel leads back to their source.

“The muon direction is almost identical to the direction of the original neutrino, so we can play the game of pointing it back to its cosmic origin,” said de Jong.

That origin is somewhere in the direction of the constellation of Orion, the Hunter. However, while there are numerous active galaxies with supermassive black holes in that region, none of them was displaying activity at the time that could explain the neutrino, nor was a gamma-ray burst detected from that direction at that time.

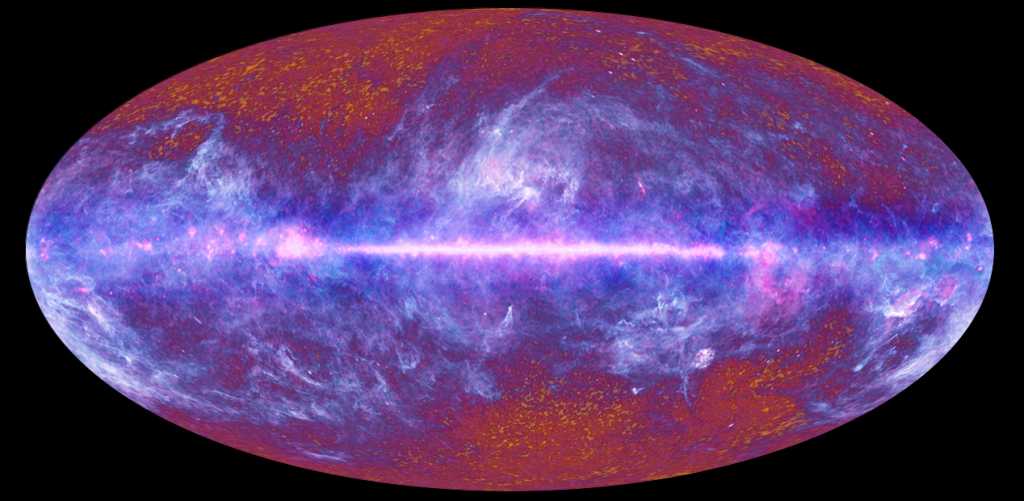

But another intriguing possibility is that KM3-230213A is the first “cosmogenic” neutrino to be discovered, produced when an ultra-high-energy cosmic ray smashes into a photon belonging to the cosmic microwave background, which is the residual light released 379,000 years after the Big Bang.

It would take an extremely energetic cosmic ray to be able to produce a neutrino like KM3-230213A. Cosmic rays in excess of 100,000 PeV have been detected by the likes of the Pierre Auger Observatory in Argentina. Their origins are uncertain, but, in theory every time such a cosmic ray encounters a CMB photon, the collision can produce neutrinos as energetic as KM3-230213A.

The greater the cosmic-ray energy, the greater its interaction cross-section, meaning it is more likely to interact with CMB photons. The constant interactions between cosmic rays and CMB photons slows the cosmic ray, limiting their kinetic energy. This is called the Greisen–Zatsepin–Kuzmin (GZK) limit.

Related Stories:

The possibility of a cosmogenic neutrino excites de Jong. “It would be the very first observation of a cosmogenic neutrino, and it would be the first confirmation of the GZK cut-off outside charged cosmic rays — and even there the proof is ambiguous,” he said.

Furthermore, the energy of cosmogenic neutrinos can reveal the properties of these ultra-high-energy cosmic rays. This parameter is key for discovering whether such phenomena are made of just protons or heavier atomic nuclei — and, therefore, what produces them. Although KM3-230213A was the only extremely high energy neutrino detected by KM3NeT, there will undoubtedly be many more passing through Earth that go undetected. Does KM3NeT’s early detection with ARCA bode well for finally being able to detect such neutrinos more regularly?

“We certainly hope so!” said de Jong. “But realistically, other experiments such as IceCube have been taking data for longer and have not observed such an event, so we could simply have been lucky.”

The discovery was described in a paper published on Feb. 12 in the journal Nature.